Black History Month: Showcasing the Contributions of Six Faculty and Staff

A spotlight on six Duke employees who blazed a trail for others today

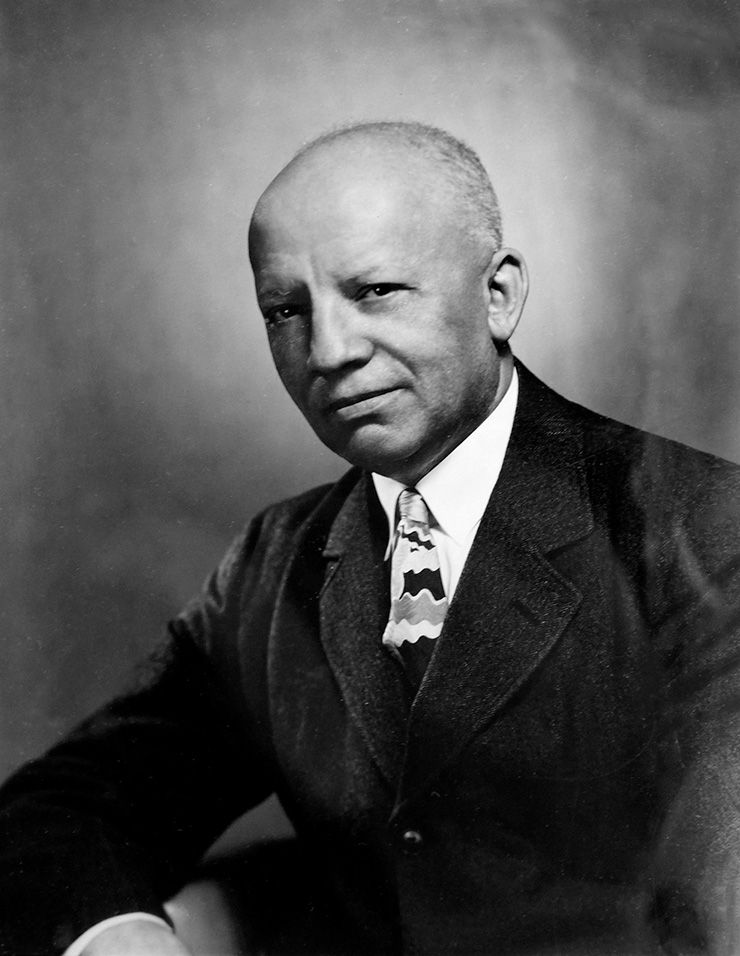

Black History Month draws its origins to February 1926, when Dr. Carter G. Woodson organized “Negro History Week,” a celebration that honored the contributions of African Americans with activities such as parades, history clubs, speeches, and more.

Woodson, who founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, was one of the first historians to study African American history. Eventually joining the faculty of Howard University, Woodson spent his life documenting Black history as a means of clearing up the story of the United States and instilling a sense of pride in Black Americans.

“If a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated,” said Woodson, known as the “father of Black History Month.”

Over the decades, the celebration of the historic contributions and heritage of Black people expanded to schools and cities and covered one month. In 1976 – years after Woodson’s death – then President Gerald Ford recognized Black History Month federally for the first time.

In the spirit of Woodson, Working@Duke is showcasing the contributions of six Black staff and faculty at Duke — Samuel DuBois Cook, Mary Lou Williams, John Hope Franklin, Brenda Armstrong, Oliver Harvey, and Phail Wynn — all of whom blazed a trail during their time that resonates in communities today.

Paving the way for Black faculty

The same week Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at Duke University in November 1964, Dr. John H. Hallowell, chair of the Political Science Department at Duke, met one of King’s Morehouse College classmates, Dr. Samuel DuBois Cook, for the first time in Durham.

Hallowell, impressed by Cook’s speech at a Southern Political Science Association meeting at the Jack Tar Motel in Durham, invited Cook, then chair of the political science department at Atlanta University, to Duke’s campus later that year.

When Cook returned, he was offered a position as a faculty member in Duke’s Political Science Department, making him the first Black faculty member at a white southern university in 1966.

Today, Cook is remembered not only for his scholarship, but as a figure who challenged the segregation on campus. Always kind and ready to mentor, Cook connected with the Black community at Duke and in Durham, helping to mediate important moments on campus, like when students in the Afro-American Society occupied the Allen building to push for improved conditions for Black students and staff.

“One of the important things to take away is that it only takes one person, and it only takes a will to make change,” said David Romine, a postdoctoral fellow for the Samuel DuBois Cook Center for Social Equity, who is writing a biography about Cook.

While a symbol of change to the first Black students at Duke, Cook wrote in his personal journals that he considered his impact to be the greatest on white students, who respected him as their favorite professor. Pushing for diversity and inclusion, Cook set the stage for a wave of Black faculty members at Duke starting with the Black Faculty Initiative.

In 1997, Duke University established the Samuel DuBois Cook Society to honor the work of Dr. Cook. Through annual awards, the society, part of the Office for Institutional Equity, honors Duke students, faculty and staff who nurture a sense of community and belonging for Black community members on campus and foster positive relationships with Durham’s Black communities.

“One of the reasons why Dr. Cook coming to Duke succeeded as well as it did was because the person they chose to be the first was a truly exceptional and thoughtful person who took the opportunity and turned it into something that forged a path forward that others could follow with ease,” Romine said.

Changing the trajectory of the Music Department

A New York Times obituary in 1981 described pianist, arranger, and composer Mary Lou Williams as “the first woman to be ranked with the greatest of jazz musicians.”

A New York Times obituary in 1981 described pianist, arranger, and composer Mary Lou Williams as “the first woman to be ranked with the greatest of jazz musicians.”

After all, she worked with Duke Ellington, Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie, among others.

“She was an innovator and a significant contributor to American culture,” said Dr. Anthony Kelley, associate professor of the Practice of Music at Duke. “You don’t have to say she was a woman; you don’t have to say she was Black; you don’t even have to say she was at Duke. She’s one of the most important innovators.”

After a career that started in the 1920s, Williams arrived at Duke University in 1977 to teach and serve as the Department of Music’s first Artist-in-Residence until her death in 1981. The move to hire Williams was one that didn’t have much precedent in higher education, Kelley said, even setting aside that she was a Black woman.

Compared to more classical forms of music, jazz was not acknowledged at the time as a serious discipline. Williams changed that, establishing the genre as part of the fabric of music at Duke. Today, her influence on campus lives on with the establishment of the Mary Lou Williams Center for Black Culture in 1983, as well as the Duke Jazz Ensemble, a group of 20 musicians that perform concerts, including the music of Williams.

Jazz has become as much a part of the curriculum as any other genre taught by the Department of Music, and Williams’ music finds its way into many classes taught at Duke as an important part of the history of music.

“To have had her as part of the roster of the Department of Music puts us in an echelon of a very special brand of music departments in America,” Kelley said. “When you bring in jazz, you’re bringing something that’s so quintessentially American that it’s almost like the highest octane because of the intellectual design.”

A legacy for the pursuit of truth

For John Hope Franklin, a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1995, Duke University was one of several stops along a career marked by important contributions to scholarship across the world.

By the time Franklin – one of the country’s foremost historians – was appointed the James B. Duke Professor of History in 1982 – he had already established an international reputation. His 1947 book, “From Slavery to Freedom” brought African American history into the national conversation, providing an account of the struggle for freedom of Black Americans as part of the history of the United States.

As a fervent scholar pursuing truth, his reputation aided Duke at a time of transition.

“What he brought to the Duke History Department and to Duke more broadly is the benefit of his stature,” said Dr. Adriane Lentz-Smith, associate professor of History. “Bringing him here signaled that Duke was eager to be, and willing to be, a university with a national, not a regional profile that was trying not to lie to itself about the American past and its past.”

Three namesake programs exist today in honor of Franklin: The John Hope Franklin Humanities Institute, the John Hope Franklin Center for Interdisciplinary and International Studies, and the John Hope Franklin Research Center for African and African American History and Culture. Each seeks to understand the history of the United States, larger world and humanities scholarship, as a means of plotting a way forward. After Franklin’s death in 2009, these standing centers represent the quest for truth that Franklin spent his life pursuing.

“Duke, as an institution, recognized fairly early on that he was a treasure and that we needed to acknowledge his presence, not just by naming things, but by really putting resources behind them and institutionalizing research and archives,” said Dr. Richard Powell, the John Spencer Bassett Professor of Art & Art History and Franklin’s friend.

Pushing diversity in medicine

As one of the first Black students to attend Duke University, Dr. Brenda Armstrong helped organize the Allen Building Takeover in 1969 before becoming the second Black woman in the United States to be a board-certified pediatric cardiologist. In 1979, she joined the faculty at Duke’s School of Medicine — a move that would stand to make Duke a better place to study medicine in the proceeding decades.

When asked why she returned to Duke to teach, Armstrong said, “she had unfinished business with Duke, and her desire was to make Duke live up to the greatness that she knew it had the potential to be,” according to an article from the Department of Pediatrics.

Armstrong served as associate dean for admissions for the school for more than 20 years, and later she was named senior associate dean for student diversity, recruitment and retention. Armstrong pioneered a strategy and approach including being an early adopter of a holistic admissions process to help broaden the school's definition of excellence and diversify the students admitted to the Duke School of Medicine. She cultivated authentic relationships and invested in coalition building with institutions across the nation resulting in a richly diverse pool of applicants applying to the Duke program.

Now, her legacy for diversity is remembered with the Brenda Armstrong Award for Advancing Diversity and Inclusion, and award given out annually by the Duke chapter of the Student National Medical Association (SNMA) to faculty or residents who have contributed to the advancement of underrepresented medical students according to her vision.

“She was not shy or reserved about what she thought needed to happen, and it was very direct, in a positive way," said Dr. Mary E. Klotman, dean of Duke’s School of Medicine. “If she hadn’t pushed as hard, it might not have had a lasting effect, but she was absolutely focused on what she believed was really needed here.”

A portrait of Dr. Armstrong, who died in 2018, now hangs in the admissions office of the School of Medicine. Today, underrepresented minorities comprise 28 percent of the medical student population in the School of Medicine.

“It’s a mark of excellence in our school,” Klotman said. “I believe our workforce and particularly our professional workforce needs to reflect our community, and our community in Durham is a very diverse community.”

Improving working conditions

As a longtime janitor and supervisor at Duke University, Oliver Harvey was a community organizer. He joined Duke in 1951 and immediately began organizing the community to improve the conditions for staff on a campus that was segregated at the time and had no Black students.

“You didn’t have any equal employment opportunities, or anything like that,” Harvey reflected, according to the 2021 book, ‘Point of Reckoning: The Fight For Racial Justice at Duke University.’ “There were no Black people in the office unless they cleaned it up …”

Wage disparities among Black workers at Duke continued into the 1960s. While federal minimum hourly pay was $1.25 in 1965, Black workers earned less because universities and other non-profits were exempt from federal minimum-wage regulations. According to a 1965 article in The Chronicle, maids earned 85 cents per hour; janitors made between 95 cents to $1.05 per hour.

Harvey organized a campus effort to bring about change.

In February 1965, he established the “Duke Employees Benevolent Society” to campaign for higher pay and enhanced benefits and working conditions. By September, he transformed the group into Duke’s first labor union, the Local 77 chapter of the American Federation of State, County & Municipal Employees. Two months later, the university agreed to improve pay and benefits. Local 77 remains Duke’s largest union on campus today.

“Oliver Harvey was one of the best professors I had at Duke, though he never taught a class,” then-Durham mayor and Duke graduate Wib Gulley said in a May 19, 1988, The Chronicle article after Harvey’s death. “He taught me that you don’t have to be loud to be heard; you don’t have to be wealthy to make a difference.”

Forging partnerships between Duke and Durham

Before giving a presentation for the then-Office of Durham and Regional Affairs, April Dudash looked out over a full room in Penn Pavilion and felt a sense of nervousness creeping over her.

Then she spotted Phail Wynn, whose reassuring smile put her at ease.

The moment was emblematic of what made Wynn a perfect fit to help bridge a strong relationship between Duke and the city of Durham.

“Whether we were visiting a school or attending a fundraiser for the Durham Literacy Center or breaking ground on an affordable housing project — everywhere we went people would just smile when they saw him coming,” said Dudash, who served as the communicator for the Office of Durham and Regional Affairs in 2017 and 2018. “Everyone knew him, and he had such a warm presence about him. He was going to listen to you. He was going to get to know you, and he was going to take everything he learned and formulate it into real change for the Duke-Durham relationship.”

Serving as the first vice president of the now-Duke Office of Durham and Community Affairs for 10 years, Wynn used his connections after 27 years as president of Durham Technical Community College to develop meaningful partnerships between the Duke and the communities. He played a leadership role in connecting Duke with its community partners such as Durham Public Schools and other programs. Wynn had a reputation for listening and harnessing the resources of Duke for the benefit of Durham before his death in 2018. Colleagues fondly remember him for his love of riding his many Harley Davidson motorcycles, showing up to special occasions in a leather jacket and revving his motorcycle in the parking lot.

"Phail was in his element when he was riding his motorcycle," said Dudash, now the communications manager for Duke Regional Hospital. "When he pulled the throttle, he loved sharing that passion and excitement with others. He did the same for the Durham community while he was with us. Even now, and especially through the pandemic, his passion and excitement continues to inspire us to look for ways to support our community."

He put attention on Duke’s connection with the community in the same way.

“I think as I walk away, what I’m overall most proud of is reestablishing trust between Duke and all the various constituencies,” Wynn told Duke Today in 2018 as he prepared to retire. “The big challenge was the more you do, the more you realize what needs to be done.”

Send story ideas, shout-outs and photographs through our story idea form or write working@duke.edu.