Remembering the Black Faculty Initiative

Duke's first faculty efforts were high profile but brought few results

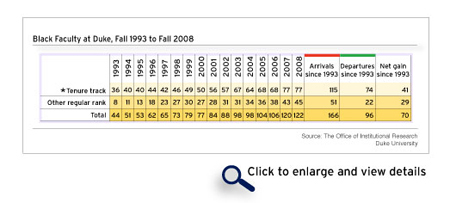

For all of Duke's success in recruiting a more diverse faculty, its initial effort is widely seen as a failure. Unlike recruitment of minority undergraduate and graduate students, it wasn't until the mid-1990s that Duke's black faculty numbers took off.

The reasons for the Black Faculty Initiative's (BFI) lack of progress and how Duke ultimately did turn the effort around continue to be important in the university's ongoing conversation about faculty diversity.

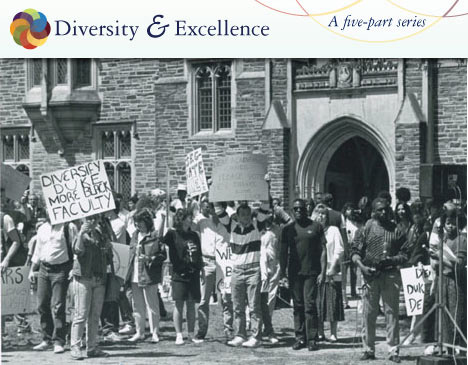

The BFI began in a truly rare campus moment: an exciting vote by the Academic Council. The only tie vote in the council's past two decades occurred on April 21, 1988, after one of the longest and most watched debates on campus since the 1960s. Spectators rimmed the outer aisles and back wall of the Social Sciences Building auditorium, and television crews waited outside for the results.

The vote was 27-27 on a crucial amendment, and for a moment there was actual suspense as to what would happen. Council chair Philip Stewart announced the vote and then broke the tie in favor of the Black Faculty Initiative (BFI). For the first time ever, Duke University set a numerical goal for hiring more African-American faculty members. Students and faculty cheered outside the room and shared hugs.

At the time of the vote, there were 31 black faculty members, including those in non-tenure track positions, out of a total of 1,399. The BFI pledged Duke to adding one African-American faculty member in every Duke hiring unit from art and art history to zoology.

There was early momentum. In 1989, Richard Powell came on as a junior faculty member in art and art history, a department that had no previous minority faculty. In 1990, two prestigious black faculty members, Skip Gates and K. Anthony Appiah, arrived to national fanfare.

The momentum wasn't sustained. The Gates hiring triggered a controversy that left many feeling bitter. Gates and Appiah left for Harvard less than two years later, with Gates referring to Duke as a "plantation."

The policy's mandate of a new hire in every department spread Duke's resources thinly. To meet the goal, many units made new hires in non-tenure track positions. Departments that had strong pipelines to minority candidates had few resources to go beyond the single mandated hire. One faculty member recalls that the focus on numbers and hiring units "handcuffed our efforts."

Richard Powell, shown in 1990, is one of three hires made during the BFI still at Duke.

When the BFI ended five years later, Duke was nowhere close to fulfilling its goal, with a net gain of only seven black faculty members. Today, only three African-American faculty member hired under the BFI remain on the faculty: Powell, Karla Holloway of English and Willie Jennings of Divinity.

Powell's hiring is an example of what Duke officials hoped the BFI would accomplish. Hired in a field that then produced few African-American Ph.D.s, Powell was a junior faculty member with a promising research record.

With the BFI, Duke hoped to improve its record of successfully guiding junior African-American faculty to receiving tenure. Nearly all of the university's notable minority faculty members -- such as Samuel Dubois Cook in political science, John Hope Franklin in history and Bert Frasier-Reid in chemistry -- were outside hires who came to Duke with tenure. Duke officials hoped Powell and others would provide a better mix of junior and senior hires.

Recalling his arrival at Duke, Powell said the BFI didn't loom large in his decision. What was more important was connections with faculty members including Caroline Bruzelius, Kristine Stiles and John Spencer in art and art history and Peter Wood in history.

"I had these connections to Duke as early as 1982, when I did evaluations of the art museum's African collections," Powell said. "What was more important [to recruiting me] was that talking with these people, I became convinced that Duke was a good match for me.

"The ‘target of opportunity' hires are always points of debate within a university," said Powell, who led several job searches himself in the five years he served as department chair. "There's a sense that a department is out there thinking just about demographics or ethnicities. What people forget is that ethnicity alone doesn't make things happen. It's all about what the hire brings to the department. Is there a synergy? Is this someone who can be a viable colleague for years? If that doesn't work, nothing else matters."

As the BFI expired in 1993, Duke tried again with the Black Faculty Strategic Initiative (BFSI), setting the goal of doubling the number of regular rank black faculty, which includes both tenure track faculty and contract faculty with specific titles such as professor of the practice and research professor.

The plan, which received support from faculty members who had opposed the BFI five years earlier, provided university financial support for some black faculty hires, mechanisms to work with departments on tracking and recruiting minority candidates and resources to help retrain black faculty who had been hired.

One valuable strategy was using "draw-down" university funds. For certain hires, the BFSI provided university money to pay for the entire costs of the faculty member's first year. Over the next five years, the percentage of university money would "draw down" and the proportion of departmental money would increase.

This effort provided incentives for departments to recruit minority candidates, but it also forced departments to get high-quality candidates because ultimately they were responsible for all of the faculty member's salary after five years.

Lauded as a more practical tool than the BFI, the new BFSI started producing results.

But even here, university officials found challenges.

"When I became provost halfway through the BFSI, our numbers showed we were doing better with non-tenure track faculty than with tenure track faculty," said Duke Provost Peter Lange. "One of the first challenges we faced was shifting the balance because we didn't want a concentration of the new hires being in non-tenure track positions."

The development of the 1996 and 2001 university strategic plans marked another change for diversity recruitment. Subtly, the philosophy behind the initiative stopped stressing numbers (without eliminating numerical goals) and started emphasizing the importance of diversity in improving the quality of the faculty and in making Duke a truly international university.

While the university still kept count of numbers, by placing recruitment in the strategic plan, the rationale for the effort became more about increasing the quality of the faculty and increasing the international stature of the university's teaching and research mission, Holloway said.

"Ultimately, recruiting minority faculty members was an effort to see what Duke might do to make itself a better institution," said Holloway, who in the mid-‘90s was involved in many faculty recruitment efforts as dean of the humanities.

Under the BFSI, Duke also had success in retaining black faculty members, even as other universities sought to attract some of these scholars, Holloway said.

In 2002, one year before the BFSI was set to expire, the university reached its goal of doubling the number of black faculty members. By then, numbers had become only one

part of a larger goal, Lange said. The BFSI had met its goal, but now a faculty task force on diversity was encouraging Duke to take the lessons from the effort and apply them to a broader measure of diversity.

"We had clearly broken out of that deadlock that handicapped the BFI," Lange said. "Now it was clear that we needed to sustain the commitment we saw in the BFSI, but that diversity had a broader meaning and was that it was critical to extend this beyond African Americans."