Alumna’s Warren County Photos Are a Part of Environmental Justice History

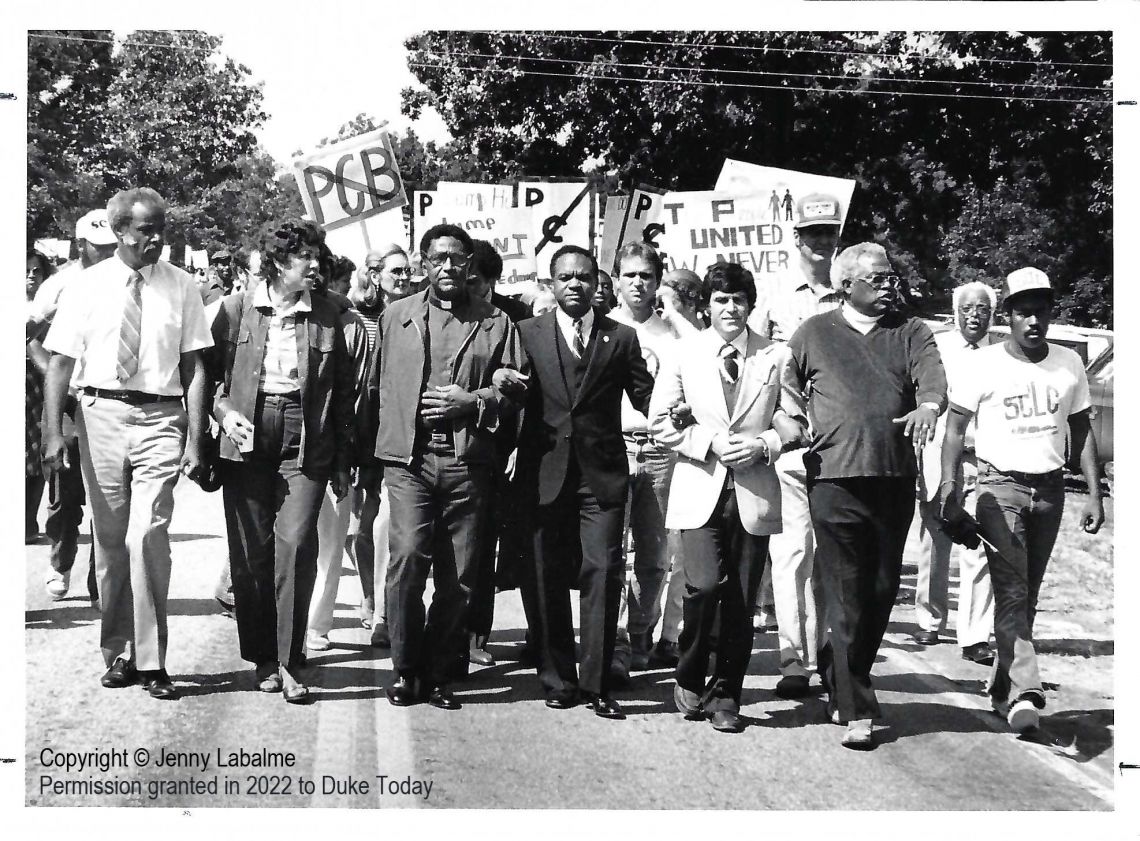

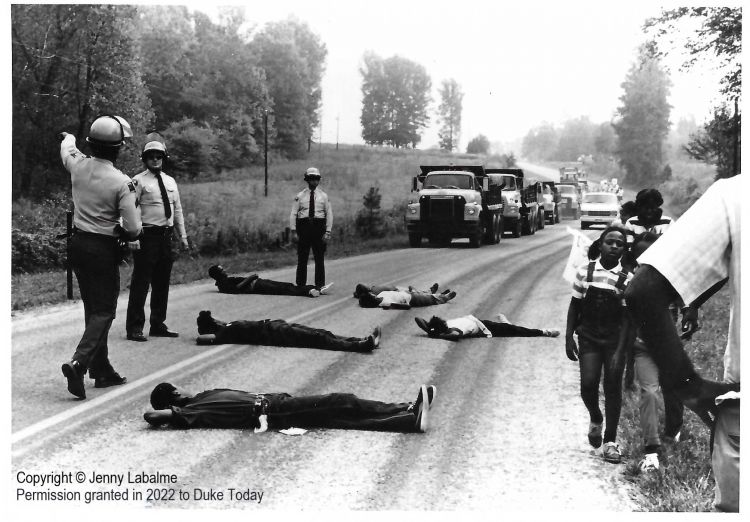

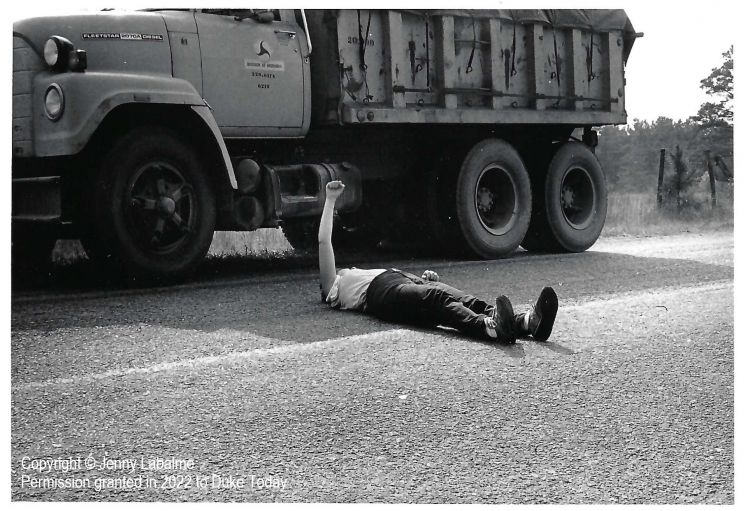

There’s a direct line from Warren County, N.C., in 1982 to Flint, Mich., in 2014 to Lowndes County, Ala., in 2022. What started as a mass protest against the dumping of toxic PCBs in Black neighborhoods in rural Warren County is now seen as one of the starting points of the environmental justice movement that is a strong voice in contemporary America.

Duke alumna Jenny Labalme, then an undergraduate student in a documentary studies course taught by Alex Harris, was on hand in Warren County in 1982 to document the moment through her photography and writing. Her photos are now, in the words of Harris, “an important part of environmental history.”

This fall, as Duke alumnus Rev. Ben Chavis and other surviving activists from the Warren County protests join with a new generation of environmental activists to mark the 40th anniversary of the demonstrations, Labalme’s photos are a central part of the effort to tell their story and inspire others to action.

As a Duke student from New York, Labalme had little knowledge about the small rural North Carolina town, just east of Henderson. But she was intrigued by the story of a marginalized community that had found its voice and power in protesting the PCB dump in the predominantly Black community of Afton.

“I think for me it was a little intimidating,” Labalme told the Henderson Dispatch in a story this month, explaining that she felt awed by working aside experienced professional newspaper journalists with “multiple cameras and way longer lenses.”

Labalme spent much of the semester familiarizing herself with the community and connecting with the people, some of whom she remains in touch with four decades later.

“Something really just struck me in my soul,” Labalme told the Dispatch, “and I said I have to come back up here again and photograph this protest in the community.”

The struggle lasted years, with Chavis and more than 500 protesters getting arrested. But the activism provided a foundation that brought political change to Warren County. Ultimately, the state acted to detoxify the landfill, a five-year process that was completed in 2003.

After Labalme graduated from Duke, she published a book of her photographs of the protests called “A Road to Walk.” She recently took the further step of posting online many of the photographs and her writings on the movement so that the history of the event would remain accessible.

Labalme went on to become a journalist with Durham’s Independent weekly magazine, now the INDY Week, as well as papers in Indianapolis and Aniston, Ala. She is currently the executive director of the Indianapolis Press Club Foundation, a non-profit organization that supports student journalists at Indiana colleges and universities.

To Harris, Labalme’s work represents the spirit of the early years of documentary studies and how Duke continues to find transformative approaches to learning and builds partnerships with others in the community to address social problems.

Harris and colleague Robert Coles taught students to use photography to get “to know people over time,” Harris said. Through this process, “students’ photographs and writing began to challenge their own earlier assumptions about other groups, allowed them to see aspects of themselves in the people they were spending time with, in short to have a transformative life experience.”

Duke’s commitment to documentary work expanded, and Duke established the Center for Documentary Studies in 1989. Harris said documentary photography remains valuable, both as an approach to learning and as a means for faculty and students to engage with the wider community.

“Because of the omnipresence of phone cameras, people are taking more photographs and making more videos than at any other time in history. Yet in the contemporary world, the U.S., and North Carolina, events lead us to the conclusion that the ubiquity of images is not helping us to see one another more clearly.”

As smartphones make cameras ubiquitous, more students arrive on campus as experienced imagemakers but programs such as CDS remain important, Harris said, to ensure that students use “their cameras as a way of getting to know other people, as a way to explore in depth the world around them, as a way to tell stories about complex individual lives we wouldn’t otherwise see or know.”

“At the Center for Documentary Studies, we believe that now more than ever, our goal to teach humanistic visual literacy to a new generation is a crucial and unique part what Duke has to offer,” Harris said.