Out at Work

Cultivating a climate of inclusion for Duke’s LGBTQ workforce

A photograph of a white paddleboard greeted August Burns when she walked up to her office door after returning from her wedding and Montreal honeymoon in 2012.

A message read, “Congratulations! This will be showing up at your door. Love, your Duke family.”

Graduate students and colleagues in the Fitzpatrick Institute for Photonics purchased the paddleboard as a wedding present for Burns and her wife, Denise, who love paddling with students and coworkers on the Haw River and Jordan Lake.

“I was so overwhelmed by the gift I had to sit down,” said Burns, 47, business manager for the Fitzpatrick Institute for Photonics. “The fact that the students and my coworkers were so supportive of my marriage was indescribable. I will cherish that moment forever.”

“I was so overwhelmed by the gift I had to sit down,” said Burns, 47, business manager for the Fitzpatrick Institute for Photonics. “The fact that the students and my coworkers were so supportive of my marriage was indescribable. I will cherish that moment forever.”

Duke’s health care benefits for same-sex partners were a driving factor for why Burns joined Duke in 2007, after working at two other organizations.

“Duke was the first employer I felt comfortable sharing with that I was gay,” she said.

From 1995 until gay marriage was legalized by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2015, Duke provided same-sex partners of Duke employees with health care benefits, and continues to cultivate a climate of inclusion for its community of LGBTQ – lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer – staff and faculty through institution-wide policies, medical learning and supportive resources. Forbes has ranked Duke among "Best Employers for Diversity" in 2019.

A commitment to LGBTQ-inclusive policies offers peace of mind and boosts confidence and morale, considering 46 percent of LGBTQ employees in the U.S. do not feel comfortable being out at work, according to a 2018 national study by the Human Rights Campaign, the largest national lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer civil rights organization.

“We want all voices to be heard about diversity, inclusion and respect, and we want to send a message loud and clear that all voices should be heard,” said Cynthia Clinton, assistant vice president of Duke’s Office for Institutional Equity.

‘I walk with my head up’

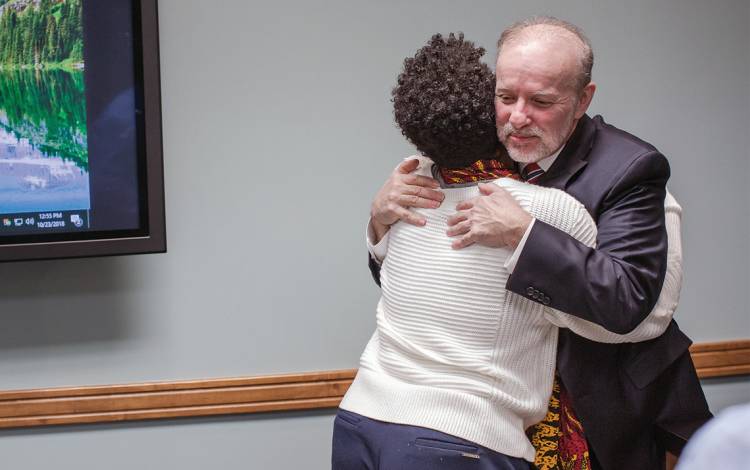

As students and staff mingled in the Center for Sexual and Gender Diversity’s fall open house, Brittney Brown, the center’s office coordinator, walked from group to group introducing herself with one question: “Are you a hugger?”

Dressed in a crisp white button-down shirt, dark slacks and black suspenders, Brown, who is gay, is right at home at Duke, maintaining the Center for Sexual and Gender Diversity’s schedule, budget and office supplies.

“When I wear what I’m comfortable in, I walk with my head up and I’m friendlier,” said Brown, 30. “With me being able to express myself, I’m open and willing to do anything and everything that’s asked of me at work.”

Brown, who joined Duke in 2009, feels especially secure because of Duke’s nondiscrimination policy, which was amended in 2007 to cover “gender identity” and again in 2016 to include “gender expression.” The changes were made following recommendations by the Duke University LGBT Task Force and engagement with a wide range of students, staff and faculty.

Established in 1991 by former President H. Keith Brodie, the task force makes ongoing assessments of attitudes and conditions throughout the university regarding gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender community members and issues.

“It’s one thing for Duke to say, ‘Our policy says you can’t discriminate,’” said Damon Seils, task force member and clinical research communication specialist for the Duke Clinical Research Institute. “It’s another thing for the university to organize a group to think through what policies mean in the real world with real people.”

Supportive language and policies at Duke have evolved over time. In 1989, the Board of Trustees first added “sexual preference” to Duke’s nondiscrimination policy, which was later updated to “sexual orientation.”

Supportive language and policies at Duke have evolved over time. In 1989, the Board of Trustees first added “sexual preference” to Duke’s nondiscrimination policy, which was later updated to “sexual orientation.”

In 1992-93, under Brodie, the task force recommended that Duke add same-sex partner benefits, but it took a few more years to come to fruition, and in 1995, when Nan Keohane was president, Duke extended health care benefits to same-sex partners of employees, bringing Duke in the same company with about 30 other universities at the time.

That change was a reason why Sara-Jane Raines, a Duke alumna and assistant chief of the Duke University Police Department, has stayed at Duke for 30 years.

“I remember thinking, ‘This is going to be a good place to work,’” said Raines, co-chair of the LGBT Task Force. “That was a really important step Duke took to let its employees know this is a place that was going to accept them and their concerns.”

In 2015, when same-sex marriage became legal, Duke updated its policies and plans so same-sex married couples had the same legal access to benefit coverage and tax filing status as married opposite-sex couples.

August Burns, whose wife was on her health plan for five years, was among 82 employees using Duke’s same-sex benefit before her marriage was legally recognized following the U.S. Supreme Court ruling.

“It felt like Duke had our back by providing benefits to both of us before our marriage was legally recognized in North Carolina,” Burns said. “We could stand up tall against any challenges because of Duke’s support.”

Teaching Through Experience

At the start of his presentation on gender medicine in Duke Family Medicine Center last fall, Blaine Paxton Hall took a moment to introduce himself.

He told the dozen physician assistants and faculty members about his credentials: author, physician assistant and adjunct associate professor for the Department of Community and Family Medicine at Duke.

“I also transitioned more than 30 years ago,” he said.

Hall underwent female-to-male gender confirmation surgeries in North Carolina in 1983, but he said he kept it a secret for 20 years because he feared for his safety and his career.

“I had to live in deep, deep stealth,” said Hall, 66, who recently retired from Duke after 22 years of service.

His experiences as a patient undergoing female-to-male gender confirmation surgeries and as a health care provider treating patients seeking hormone therapy led Hall to start Duke’s first adult gender medicine clinic in January 2018. It complements Duke’s Child and Adolescent Gender Clinic, which opened in 2015.

The Adult Gender Medicine Clinic in Duke Health provides gender-affirming hormone therapy to intersex patients and people with gender dysphoria, the distress a person feels when their assigned gender does not match the gender with which they identify.

According to a 2015 report by the National Center for Transgender Equality, a nonprofit advancing the equality of the transgender community, nearly a quarter of transgender people in the prior year needed health care but did not seek it due to fear of being disrespected or mistreated as a transgender person.

According to a 2015 report by the National Center for Transgender Equality, a nonprofit advancing the equality of the transgender community, nearly a quarter of transgender people in the prior year needed health care but did not seek it due to fear of being disrespected or mistreated as a transgender person.

“From the point of view of the patient, I cannot tell you how important it is to them that they can say, ‘Oh, he really understands because he’s been there. He went through it,’” Hall said. “I would have given anything to have known any doctor who also had my experience.”

Teaching has been a large part of Hall’s role. He is one of the authors of the current World Professional Association of Transgender Health Standards of Care and has presented to School of Medicine students and Duke Health staff on ways to best care for transgender patients.

Duke will include transgender awareness in an upcoming discrimination and harassment compliance training video. In the video, a mock scene shows an employee overhearing two coworkers intentionally referring to a transgender person by the wrong gender pronouns. The scene illustrates that refusing to acknowledge someone’s gender identity is inappropriate and disrespectful.

“To reject another person’s gender identity is to imply that you know more about that person than they know about themselves,” Hall said. “The fact is you don’t. Gender is at the core of one’s identity as a human being.”

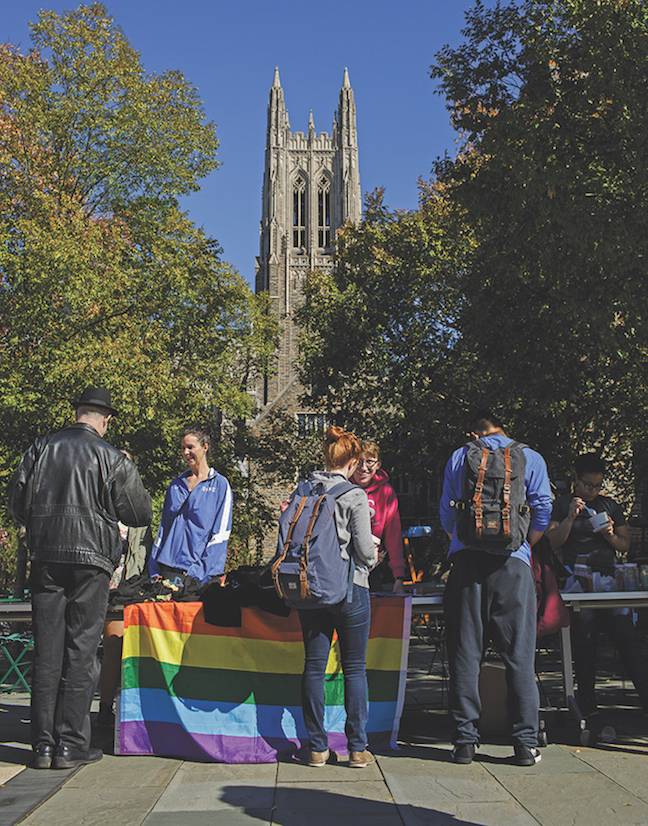

A Space to Connect

In between bites of tamales and grilled cheeses, several Duke employees sat in Divinity Café one afternoon discussing Duke’s libraries.

Ciara Healy, an associate librarian at Perkins Library, led the discussion while Kevin Wilson, benefits specialist for Duke Human Resources, and Matt Bailey, a residence coordinator for Central Campus, listened.

The three never would have met without WorkOUT, Duke’s LGBTQ staff and faculty group.

“LGBTQ people are all over Duke, so WorkOUT provides a central place to connect them,” said Wilson, WorkOUT co-founder. “It’s important to have a space where you can relax and be yourself. It’s comforting to be around people who identify similarly to you and have shared experiences.”

WorkOUT, which meets for lunch once a month and hosts socials at Durham restaurants, is one of several resources at Duke for the community and its allies. The Center for Sexual and Gender Diversity runs “Duke P.R.I.D.E. Training,” “Trans 101” and “Asexuality 101” workshops year-round for all employees and students. And the School of Medicine’s Office of Diversity & Inclusion created the Duke Health OutList for openly LGBTQ and ally health care professionals.

The workshops hosted by the Center for Sexual and Gender Diversity cover topics such as language and identities and the experiences and challenges transgender and asexual community members face.

Sheeva Marvdashti, a physician assistant for Duke Cancer Center’s Breast Surgical Oncology team, attended a “P.R.I.D.E. Training” workshop last year to learn how to better address her patients.

“I have a tendency to say ‘mister’ or ‘missus’ when addressing patients,” Marvdashti said. “Attending the workshop helped me understand that addressing someone that way means I’m assigning them a gender they may not identify with.”

The Center for Sexual and Gender Diversity also maintains OUTDuke, a list of faculty and staff whom community members can contact as an informal resource.

Much like OUTDuke is a supportive resource, the School of Medicine’s OutList is intended to help Duke Health students with mentorship and research.

Sharon Hull, director of executive coaching for the School of Medicine, is among about 200 employees on the OutList. Hull, who is gay, joined to let students and employees know she is available to help.

“There was a long period of my professional life when I was not out,” said Hull, 56, who joined Duke in 2013. “As I’ve gotten older, it’s become important to me that students can have a role model who is out at work.”

Seeing more LGBTQ employees in leadership roles is something Andy Brantley hopes to see in the next five years. Brantley is president and CEO of the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources, which provides leadership on higher education workplace issues in the U.S. and abroad.

He said higher education has a clear commitment to creating a more diverse and inclusive workplace. Where institutions falter is implementing that commitment across departments and as part of campus culture.

“Duke is very much at the head of the curve for creating diverse and inclusive environments for staff and faculty,” Brantley said.

He describes progress in the LGBTQ workforces as an ongoing journey.

“It's a lifelong commitment to learning, and growing, and accepting others, and engaging others, and growing ourselves as leaders, as managers, as citizens overall,” Brantley said. “We’re all learning and growing together.”

Have a story idea or news to share? Share it with Working@Duke.