Who Are We?

Generations in Duke’s workforce are nearly evenly split, more than half of employees are female, and efforts are underway to diversify faculty

Nearly five years ago, Working@Duke delved into the question of who we are as a workforce. For this report, we take another look and discover that Duke’s workplace is changing, especially when it comes to age. Duke employs 37,000 faculty and staff who represent a diverse and unique community – from age, race, ethnicity, and LGBTQ to national origin, political persuasion and religious background. In this special report, Working@Duke focuses on age, female leadership, minority hiring and global representation.

••••

As a clinical nurse in Duke University Hospital, Ellen Rottner helps patients bathe, eat and walk the halls to gain strength after surgery.

She is a millennial supervisor who, as a clinical lead, helps share ideas between bedside nurses and hospital administrators while mentoring nurses, overseeing 32 patients on the unit, and interviewing and orientating new employees.

More than half of Rottner’s colleagues in the General Surgery Step Down Unit were born between 1980 and 1995,

the age range for millennial employees in Duke’s workforce.

“Over the last few years, our unit has definitely changed into a much more millennial unit,” said Rottner, who turns 28 in April. “It seems like it’s getting younger and younger.”

The number of millennial staff and faculty across Duke University and Duke University Health System is increasing while other generational groups, including Baby Boomers and Veterans, are declining in population. In 2015 alone, Duke’s millennial workforce grew by 9 percent, according to Duke Human Resources.

At Duke, the number of workers in the Millennial, Generation X (born 1965 through 1979) and Baby Boomer (1946 through 1964) generations is nearly evenly split into thirds. With the youngest of Baby Boomers about 15 years away from retirement, meeting the needs of all demographics in a workforce is becoming a growing challenge for employers, Mercer, a global consulting firm, noted in its 2015 “Inside Employees’ Minds” report.

To keep up with evolving generational needs, Duke’s Learning & Organization Development offers a new professional development course, “Managing Across Generations,” to help staff and faculty better understand behaviors and values of generations.

Wendy Sprintz, manager of clinical education and events for Duke Clinical Research Institute Communications, enrolled in the class to learn more about how generations communicate.

A Baby Boomer, Sprintz said employees in her office range from right out of college to those who have been at Duke for more than a decade. She said younger colleagues prefer emailing and texting, but Sprintz is inclined to chat in-person or by phone.

“Millennials are the people who are going to carry us to the future,” she said.

According to the Pew Research Center, millennials surpassed Generation X to become the largest segment of the American workforce in 2015. Currently at Duke, about 11,500 millennials comprise the employee population of 37,000. But generational perspective is only one aspect of Duke’s workforce.

5 out of 10 Deans are Female

Valerie Ashby began her academic career as a chemist. She didn’t plan on becoming a university dean.

But in 2015, Ashby landed at Duke as dean of Trinity College of Arts and Sciences, where she serves 650 faculty members, 300 staff and about 7,000 students.

She is one of five female deans at Duke, which has 10 main graduate and professional schools. The most recent dean appointment, Dr. Mary Klotman for the School of Medicine, was announced in January.

“I don’t think it actually occurred to me that we had so many female and/or minority deans at Duke,” Ashby said. “It’s pretty tremendous … It is a gift to have such a diverse group of colleagues.”

Across the U.S., about half of higher education administrators are women, but the percentage of women represented in top executive positions remains less than 30 percent, according to a survey by CUPA-HR, an association for Human Resources professionals in higher education.

At Duke University, women comprise 55 percent of the executive/administrative job category, a 2-percent increase since 2015, according to Duke’s 2016 Affirmative Action Plan. The job category includes executives, university officials, senior directors and administrators. Sixty-five percent of Duke’s total workforce is female, according to Duke Human Resources.

“Opportunities are currently evolving across Duke for mentoring and leadership development for women,” said Kyle Cavanaugh, vice president for administration. He noted the Duke Leadership Academy, a 12-month program for employees, which graduated 15 women of 26 staff members in December.

The Academic Council’s Task Force on Diversity Report proposes forming a “robust process” for identifying women internally and externally, along with underrepresented minority faculty and faculty candidates, with leadership potential.

“We have made great strides, but I don’t think there is any moment when we should become less vigilant,” said Anathea Portier-Young, co-chair of the Duke Faculty Women’s Network and Caucus and associate professor of Old Testament in Duke Divinity School. “Being able to see oneself in Duke’s leaders, I think for many people, ... is an incredible gift.”

Reflecting the Diversity of Students

Martin Smith has taught at Duke for two semesters, but he has made a lasting impression on students.

Martin Smith has taught at Duke for two semesters, but he has made a lasting impression on students.

He’s a 32-year-old black assistant professor of the practice with a penchant for research and black history. As part of Duke’s Program in Education, he created a new course about athlete activism and black issues in America called “Race, Power and Identity from Ali to Kaepernick.” He also helps black and Latino Duke students share life stories through an independent study, “The Art of Storytelling.”

“When I first started, I had students who sought me out and said, ‘You know, I’m really interested in taking your course,’” Smith said. “‘I’m really interested in hearing your perspective because I’ve never had a professor who looks like you.’”

At Duke University, minority faculty members, which include men and women who self-identify as Hispanic, Black, American Indian, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, or two or more races, comprise 23 percent of the total regular rank faculty population of 3,429, according to Duke’s 2016 Affirmative Action Plan. Duke’s undergraduate student population is about 50 percent diverse.

“It’s important for students to see a diverse group of faculty members who reflect the diversity of our student body,” said Duke Provost Sally Kornbluth. “I very much hope that ultimately our faculty diversity can mirror what we’ve been able to achieve at the undergraduate level."

Duke’s strategic plan, as well as the Academic Council’s Task Force on Diversity, proposes ways to increase faculty diversity and build a more inclusive environment. This includes creating diversity and inclusion committees in schools and departments and ensuring search committees bring in diverse faculty applicants.

From fiscal year 2015 to 2016, minority faculty hiring at Duke grew by 16 percent, according to Duke Human Resources.

Assistant professor Angela Richard-Eaglin, who is black, was hired last August to teach at Duke’s School of Nursing. During her first month, the school organized diversity and inclusion focus groups for faculty of similar races and ethnicities to discuss workplace culture.

“The world is diverse, so the workplace needs to be, too,” said Richard-Eaglin, who has spent much of her career working with underserved populations.

A World of Opportunity

As the university broadens its global presence, a small office tucked away in Smith Warehouse near downtown Durham serves as the gateway for a growing international community that calls Duke home.

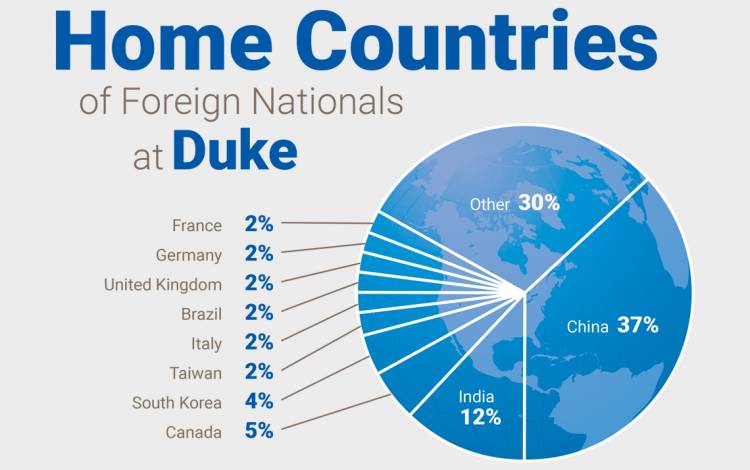

Duke Visa Services helped 3,279 citizens from other countries become part of Duke’s workforce in the past fiscal year – an increase of 17 percent since 2011.

International travelers arrive at Duke as students, research assistants, visiting scholars, professors, research scientists, and post-doctoral fellows from more than 120 countries ranging from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe. Obtaining a visa to work in the United States can take months, and in some cases, more than a year, but that hasn’t slowed the pace of people coming to Duke.

“Many people from around the world want to come to America to do additional research and become the best in their fields,” said Lois Yelverton, director of Duke Visa Services who has worked in the department for more than 20 years. “These people are smart, innovative, and provide a valuable service to the university. They also create a cultural learning opportunity for us, too.”

Opportunity prompted Maryam Baikpour, a visiting research scholar, to seek training and research experience in obstetrics and gynecology at Duke last year after completing her medical degree in Iran.

Baikpour’s plans date back to high school when she watched the sitcom “Friends” to improve her English-speaking skills. To earn enough money to travel to the United States, she worked in the impoverished county of Kouhrang, Iran, where she saw about 100 patients daily for two years.

“At Duke, I’ve worked on research projects, attended clinic, participated in classes and conferences, and learned how to design randomized controlled trials,” she said. “Having seen how the Duke Fertility Center is set up, I would love to set one up in Iran. There is such a shortage of physicians in the region I served that midwives perform C-sections. It’s illegal, but they have no choice.”

As Baikpour plans the next steps in her career, she credits Duke for offering her and others options that are not available to them in their countries.

“I am thankful to Duke University for allowing international medical students to work here because it’s an investment for them to do this,” she said. “I’m very grateful for the opportunity.”