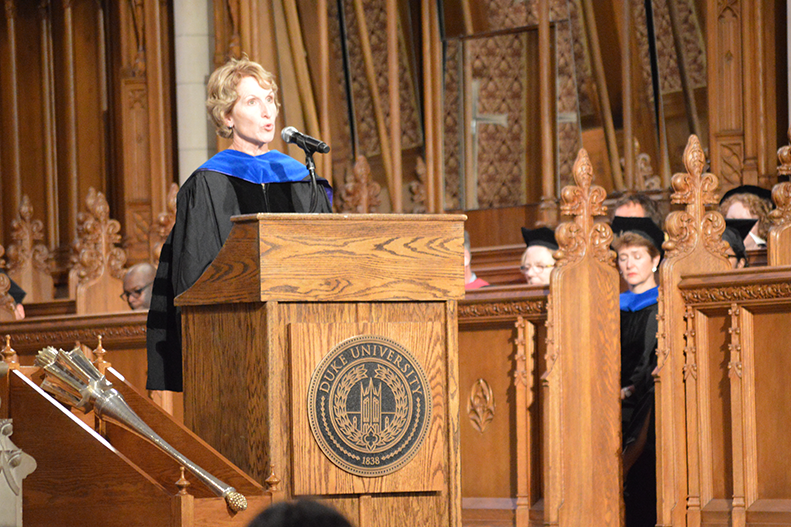

Susan Lozier: Learning About All the Places We Will Never Go To

2016 Graduate and Professional Convocation: Professor Describes the Community of Scholars

Over 50 years ago on a warm morning near the start of summer, a 6-year old sat wedged between her sisters in the back seat on the drive home from church. Thinking of picnics and fireworks, she asked a simple question, “When is the 4th of July?”

That question alone was enough to elicit smirks from her older sisters, but the full question she asked that morning was, “When is the 4th of July, June what?”

I think my fate as a scholar was sealed that summer morning. Clearly, I was not afraid to ask questions, am still not afraid to ask questions or as my sisters put it “She has never been afraid to ask the stupidest of questions”.

I have always wanted answers.

And so, even more than the laughter of my sisters, I recall my mother turning slowly around, looking at me with all seriousness and saying “The 4th of July Independence Day, is on July 4th….and for good measure she added, “every year.”

Well, that was good to know. I have not forgotten since, nor have my sisters.

In its simplest form, scholarship is the pursuit of answers to questions that we don’t know.

Answers to those questions might appear at the close of a book or a class; at the end of undergraduate or graduate study; or perhaps at the close of an entire academic career.

Some questions though go unanswered for centuries, if not forever.

Adelard of Bath, an English naturalist in the early 12th century during the reign of Henry the First, assembled a list of unknowns about the natural world.

Among the 76 questions in his Treatise on Nature are:

- Why are the waters of the sea salty?

- How do the oceans not increase from the flux of the rivers?

- Whence comes the ebb and flow of the tides?

Nine hundred years later, we have answers to these questions, yet others that Adelard asked remain puzzling:

- Why is joy the cause of weeping?

- Do beasts have souls?

Had Adelard lived during the reign of Henry II, rather than Henry I, he might have journeyed to Oxford to discuss these questions among the learned scholars assembled there.

All those centuries ago, and all centuries hence, universities have been a magnet for those with questions.

Universities were - and are still - home to great libraries and great scholars. What one could learn in Bologna, Paris, Padua, Oxford, Salamanca or Al Azhar was immeasurably more than one could learn even a few miles from the walls of these universities, much less thousands of miles away.

Watch the 2016 convocation for new graduate and professional students. The ceremony begins at 18:37.

The divide between those with information and those without was wide, and could be measured in miles.

Today, almost anyone with a smart phone in almost any part of the world could, in a matter of time that I do not care to estimate, find most if not all of the information that I teach my students over the course of a semester.

Do you want to know what the temperature of the Earth would be if it had no ocean or atmosphere? Do you want to know why and where the winds blow? Why tropical rains are so intense?

Just google it.

The digital age has democratized access to information; information is ubiquitous, free and available to everyone.

Why then come to a university in the 21st century? What is the magnet now?

Access to information is crucial to learning; but information is not knowledge.

We have information on the shifting climate patterns, but how do we understand those patterns in the context of Earth’s climate history? How do we use those patterns to anticipate and plan for Earth’s future climate?

We have information on the unfolding migration crisis across Europe. We see photographs of utter despair. But, how do we understand the stark choices these refugees face and how do we reconcile our action or inaction?

We have information on disease, on incarceration rates, on neutrinos, on public art, on your web searches and mine. How do we make sense of all this?

The university offers the incomparable advantage of placing information in its ethical, historical, cultural, political and scientific context, so that it can be integrated to produce a more comprehensive understanding of the arts, of law, literature, of medicine, of our world.

Here is where information becomes knowledge. But context isn’t static. It evolves from the creation of new ideas.

As the 20th century urban theorist Jane Jacobs observed, most new ideas are inspired directly by older ideas. The exchange of ideas then is at the heart of the university’s transformative work.

At its essence, a university is a community of scholars and learners whose collisions lead to the creation of new knowledge and understanding, which leads to a broader context on matters that matter to all of us.

The magnet is this community.

For centuries and decades past, that collection of scholars in this country was primarily a community of men with European ancestry.

But if the fundamental work of a university is to generate ideas that change our world, then we must foster encounters among individuals with different backgrounds, perspectives, histories, politics and identities so that we maximize the potential for gain. We must embrace scholars, students, and ideas that have not always been embraced.

It took my mother but a moment to answer my question about that summer holiday. Adelard’s question about the tides lingered for 500 years before Isaac Newton formulated a definitive answer.

But not all questions have definitive answers.

What is the future for American democracy? What is the full expression of religious liberty? What impedes progress on population health, on climate change on race relations across this country? What is progress?

A diverse and intellectually vibrant community broadens the envelope of answers to those questions, preparing us for the complexity of today’s societal challenges.

How do we create that community?

Today, at Duke, like many universities, there are opportunities for faculty and students to be away from the campus, either physically away because of internships, global programs and collaborations, or away virtually, through online courses, video-conferences….through our smartphones. There are, in essence, centrifugal forces pulling us apart.

What pulls us together?

A few years ago in a faculty discussion on new modes of college admission, a colleague speculated that the “industrialization” model of college education, where students are constrained to the same space during the same few years, may soon be an outdated model. In the not too distant future, she argued, students may come and go on their own schedules, at their own pace, sometimes gathering in virtual space, sometimes gathering in real space. Students would be, in effect, unbounded by spatial and temporal constraints.

An interesting idea. Yet even boundlessness has its limits.

You see, space and time constraints are precisely what create community. To have community, we need to occupy this space, this campus together…..and we need a shared commitment to intellectual engagement.

At the start of your professional and graduate education here at Duke, I encourage you to commit to this engagement. Decades ago when I entered graduate school, I had no idea of the transformation ahead of me. Like all of you here today, I had excelled in learning all sorts of things as an undergraduate – yet as a graduate student I learned how to stitch together pieces of information, how to fully comprehend and formulate ideas. I learned how to think.

And so I encourage you to look for every space where you can encounter, analyze and critique ideas and arguments. You will find those ideas and arguments in classes, in labs and in seminars, but also in hallways, in offices, in chance encounters.

Claude Debussy, a French composer in the early 20th century noted that: “Music is what happens between the notes.”

As a graduate and professional student, your education will not be defined by the time spent in class. Far from it. This Duke campus offers you the opportunity for learning at every turn.

You do not need to come to Duke to learn that the 4th of July is not in June, or that the ebb and flow of the tides is created by the gravitational attraction between the Earth, the moon and the sun, but during your time at Duke you will be surrounded by ideas that you have not thought of, voices that you’ve not heard and perspectives that you’ve not considered.

None of us will get to all corners of the Earth or have the time to explore the full complexity of human knowledge; each of us has but one history and one narrative. But a university community can broaden our understanding of those corners, that complexity and those histories. In effect it can transport us to places we’ve never been.

One of my favorite poems expresses this sentiment about being transported. The poem is:

Fishing on the Susquehanna in July by Billy Collins

I have never been fishing on the Susquehanna

or on any river for that matter

to be perfectly honest.

Not in July or any month

have I had the pleasure -- if it is a pleasure --

of fishing on the Susquehanna.

I am more likely to be found

in a quiet room like this one --

a painting of a woman on the wall,

a bowl of tangerines on the table --

trying to manufacture the sensation

of fishing on the Susquehanna.

There is little doubt

that others have been fishing

on the Susquehanna,

rowing upstream in a wooden boat,

sliding the oars under the water

then raising them to drip in the light.

But the nearest I have ever come to

fishing on the Susquehanna

was one afternoon in a museum in Philadelphia,

when I balanced a little egg of time

in front of a painting

in which that river curled around a bend

under a blue cloud-ruffled sky,

dense trees along the banks,

and a fellow with a red bandana

sitting in a small, green

flat-bottom boat

holding the thin whip of a pole.

That is something I am unlikely

ever to do, I remember

saying to myself and the person next to me.

Then I blinked and moved on

to other American scenes

of haystacks, water whitening over rocks,

even one of a brown hare

who seemed so wired with alertness

I imagined him springing right out of the frame.

________________________________________________________________

I am unlikely to do all sorts of things. Certainly, I am unlikely to see or question all there is to see or question, but as a member of this Duke community, I’m likely to learn about fishing on the Susquehanna; likely to learn more about your world, more about mine, and more about the world we share.

Welcome to this community of scholars. Welcome to deep and engaged learning. Welcome to Duke.