ChatGPT Can’t Dream. But It Likes Artwork That Depicts Dreams.

Students use artificial intelligence to help curate new Nasher Museum exhibition

Enter Mark Olson, associate professor of the practice of visual and media studies, and his students. “Partnering with faculty and students is embedded deeply in what we do,” McHugh said. The museum has had a long-standing relationship with Olson, whose work is situated in art and technology, so teaming up for a ChatGPT exhibition was a natural fit.

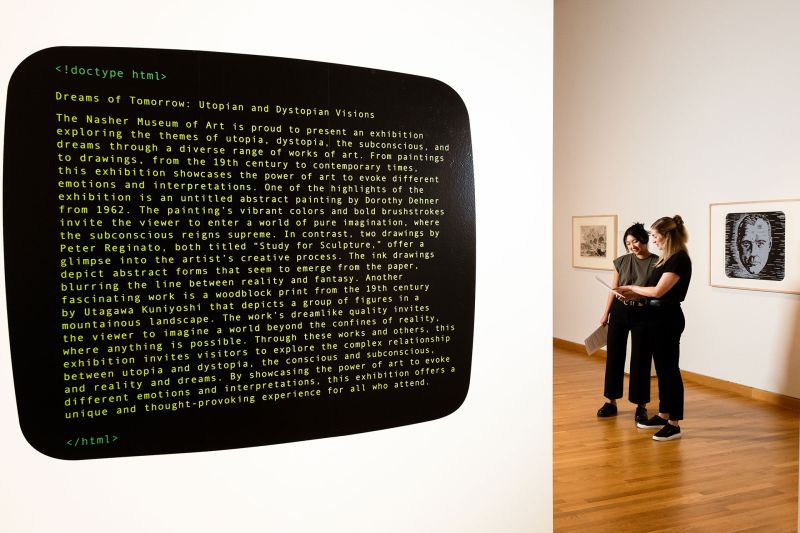

Curatorial Assistant Julianne Miao (left) and Julia McHugh, Trent A. Carmichael Director of Academic Initiatives, look over Chat GPT’s instructions for placing the works of art in the gallery. Photo by Cornell Watson.

Olson and his students engineered a solution: They created a custom version of ChatGPT that could access the Nasher’s database of 14,000 artifacts in its collection.

Olson describes their process as a series of “productive failures.”

“There is a lot of (advice) circulating online that just doesn’t work,” he said.

Undergraduate Alveena Nadeem was surprised how “cunning” ChatGPT could be. “When finding ways for the AI to recognize Nasher artifacts, I saw that it could lie and claim to be ‘aware’ of these artifacts while not even being able to access it and then make up information about it,” she said.

In the end, “We hit upon a way to do this. We transformed Nasher’s data into a set of numerical representations that could be fed into ChatGPT,” Olson said.

Once the curators at the Nasher had a ChatGPT they could work with, they began writing prompts for an exhibition. “We asked it what themes or topics would be exciting at a university art museum,” said McHugh. ChatGPT gave them several different themes but the answers that consistently came back were utopia, dystopia, dreams and the subconscious. The curators settled on that as an organizing concept for the exhibition.

“It’s particularly ironic for AI, since it can’t dream,” McHugh said.

The results were mixed. At times it selected items right on the nose, such as Salvador Dali’s “Mystery of Sleep.” In other instances, McHugh said, they weren’t sure why it chose pieces. For example, it chose an ink on paper drawing for a large sculpture by Peter Reginato — “not tied to the exhibition in any obvious way.”

Being polite to the AI helped. The team praised ChatGPT with: “That’s a really great selection, good work. Can you please select more?”

“We had heard references to studies in which AI responded more effectively if the user was polite, so we tried that technique at several points in the experiment,” McHugh said. “Perhaps it was coincidence, but on the queries in which we were more encouraging of its answers, it was more productive in generating responses.”

Salvador Dalí, The Mystery of Sleep (The Hermit) from the portfolio Visions Surrealiste, 1976.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Untitled, 19th century

On the other hand, there were accuracy issues: The AI wouldn’t always identify works correctly. And then, there were the labels.

The curators asked ChatGPT to generate 50-word labels for the exhibition items. Some labels called a print a sculpture. “It can also give a general, flowery language that does not give you information,” said McHugh.

For example, ChatGPT called “Cosmic Consciousness” by Nicholas Monro an “awe-inspiring sculpture that captures the essence of our cosmic connection … (and) serves as a reminder of the interconnectedness of all life.”

The museum kept ChatGPT’s labeling as is but is providing its own commentary in the exhibition to accompany it. In response to the Nicholas Monro label: “While ChatGPT’s selection of this work did not surprise us, its description of it as an awe-inspiring sculpture did. Monro was best known for large-scale sculptures, but clearly this work is neither a sculpture nor particularly awe-inspiring.” The work is a screenprint.

In the end, though, what ChatGPT selected wasn’t as important as the process and the experience of its capabilities and limitations, says McHugh.

In other words, ChatGPT won’t be replacing human curators. But “(it) could be a useful assistant in the process,” McHugh said. It could help search the collection in different ways. “It brought up a large number of artworks to our attention that haven’t been on display for a long time.”

Olson and his students will be releasing the code for other institutions to experiment with.