Black History Month: Legacies Behind the Names on Campus

Learn the stories of places and things named in honor of Black students, faculty and staff

Celebrate Black History Month

The Mary Lou Williams Center for Black Culture welcomes author, filmmaker and activist Kimberly Latrice Jones for a keynote speech at 6:30 p.m. Wednesday, February 8 at Page Auditorium. The event is open to the public.

Whether the Michelle Winn Awards, the John Hope Franklin Humanities Institute, the Mary Lou Williams Center for Black Culture or the Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity, pieces of Duke campus life are named after Black staff, faculty and students who shaped the course of the institution.

“The act of naming something for a person gives them a sort of immortality,” said University Archivist Valerie Gillispie. “But that’s only effective if we keep talking about them versus just seeing their names.”

In celebration of Black History Month, here are stories of some of the people whose legacies are kept alive through pieces of Duke that bear their names.

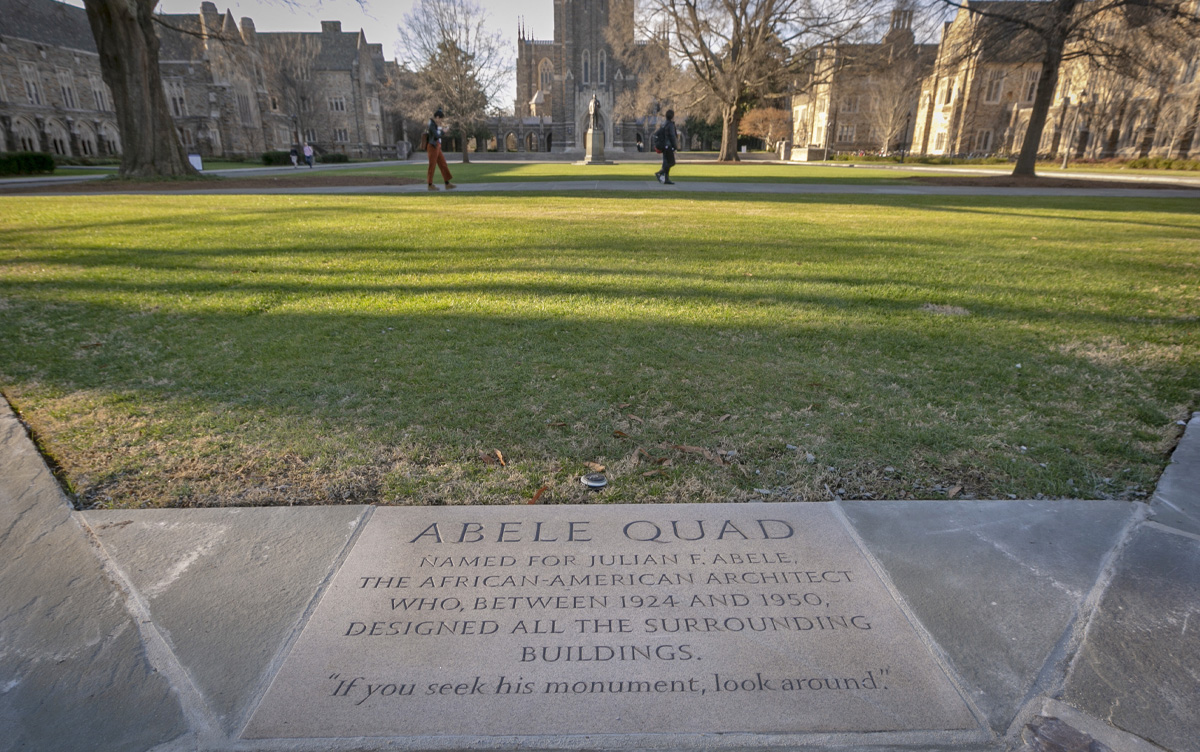

Abele Quad

In the early decades of the 20th century, Duke’s campus was rapidly evolving and expanding. East Campus was re-envisioned in the 1920s as an orderly collection of Georgian-style buildings set around a wide quad. In the 1920 and 1930s, the gothic-revival West Campus rose from what had been rolling farmland and forests.

The Philadelphia-based Horace Trumbauer architecture firm was hired to design Duke’s campus. As the firm’s chief designer, Julian Abele, the first Black graduate of the University of Pennsylvania’s architecture school, played a central role in creating all of it.

From the new look of East Campus to the design of the Allen Building, Abele designed Duke’s growing campus from the early 1920s until his death in 1950.

While Cameron Indoor Stadium, Baldwin Auditorium and Duke University Chapel are all his designs, given the racial climate of the time, his contributions weren’t emphasized. It’s unclear if Abele ever visited Duke’s campus, which, at the time of his death, had no Black students or faculty and existed in a state where Jim Crow laws limited the rights of Black citizens.

The reexamination of Abele’s involvement had its genesis in a 1986 letter to the editor of The Chronicle.

At the time, Duke students were protesting the university’s dealings with companies doing business in apartheid South Africa by building and occupying shanties in Duke University Chapel. A student wrote the newspaper to complain that the shanties were disrupting the beauty of Duke’s campus. In response, Duke student Susan Cook wrote that she was Abele’s great grand-niece, and that he would see no trouble with the protest.

“Maybe the reason I’m so certain that he wouldn’t object is because he was a victim of apartheid in this country,” Cook wrote. “He never came to Duke to see what he had created because his repulsion to the segregated South made it impossible for him to travel further south than Philadelphia.”

In the years that followed, Abele’s role in the design of Duke’s campus became more widely discussed. And in 2016, the quad at the heart of West Campus, in front of Duke Chapel, was officially renamed Abele Quad, ensuring that his contributions to many of Duke’s signature spaces won’t be forgotten.

Reuben-Cooke Building

In the fall of 2021, the West Campus classroom building known as the Sociology-Psychology Building was renamed to honor pioneering Duke graduate Wilhelmina Reuben-Cooke.

In 1963, Reuben-Cooke was one of the first five undergraduate students to enroll at Duke.

During her time on campus, she pushed for progress, taking part in civil rights protests in Chapel Hill and Durham and petitioning Duke leaders to give up their memberships to an all-white country club.

When she was selected by classmates in 1967 as the May Queen – part of the May Day celebrations, a tradition at the time at many southern schools – it created backlash from some corners of the Duke community.

“For her to step forward and take her rightful crown and deal with the fallout from that was impressive,” Gillispie said.

After graduating in 1967, Reuben-Cooke went on to become a successful lawyer, law professor, and eventually serve two terms on the Duke University Board of Trustees.

Reuben-Cooke died in 2019, but with a part of campus now bearing her name, her legacy endures.

“She will never be forgotten,” Gene Kendall, who enrolled at Duke in 1963 alongside Reuben-Cooke, told the audience at the building’s 2021 dedication. “The story, the decision, the change in history that Duke made in 1963 can never, ever be erased.”

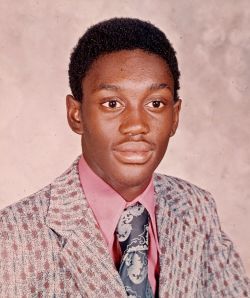

Reginaldo Howard Memorial Scholarship

As as an assistant professor of the practice in the Program in Education, Martin Smith has encountered students in classes he taught about Black history and political protests who were proud to identify as “Reggie Scholars.”

“Every ‘Reggie Scholar’ I had in one of my classes was top-tier,” Smith said. “They were really conscientious, always came to class ready to discuss everything, they just really stood out.”

Now the Trinity School of Arts and Sciences’ Dean of Academic Affairs, Smith oversees the Reginaldo Howard Memorial Scholarship program, which welcomes four-to-six new “Reggie Scholars” each year.

The scholarshop is named after Reginaldo “Reggie” Howard, who, on March 2, 1976, became the first Black student to be elected president of Duke’s student government. Roughly two months later, while returning to Durham from his home in South Carolina, Howard was killed in a traffic crash.

Since 1979, the scholarship created in his honor has given a chance for some of Duke’s brightest students to pursue their goals. Awarded to selected Black incoming first-year students, the Reginaldo Howard Scholarship covers the students’ total cost of attending Duke and provides funding for a development endeavor of their choosing, such as a period studying abroad or a research project. It also gives the students chance to join a tight-knit network of Reggie Scholars who encourage and support one another during and after their time at Duke.

“His name lives on,” Smith said. “Obviously, we all wish he was still here. But in a way, his dream is coming to fruition. He’s still leading. He’s still empowering. He’s still creating opportunities for others.”

Michelle Winn Inclusive Excellence Awards

A winner of a 2022 Michelle Winn Inclusive Excellence Award, Christie McCray wants the students in Duke University School of Medicine’s Master of Biomedical Sciences program to feel like they belong at Duke.

McCray, the program’s administrative manager, walks new students through onboarding, registration and completing paperwork needed to get important certifications. She also organizes team-building activities such as an orientation cookout and outings to the Durham Bulls.

“I think it’s very important for our students to feel like they have a place here,” McCray said. “I’m very big on the sense of belonging.”

In the past decade, roughly two-thirds of the program’s graduates have been from traditionally underrepresented populations, a credit to the welcoming climate McCray creates. Winn would have appreciated McCray’s work because she served as a mentor to many medical students, residents and colleagues and championed inclusion and diversity.

Wanting to continue her legacy after her death, colleagues of Dr. Michelle Winn and the School of Medicine’s Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, led by Associate Dean Judy Seidenstein, created the awards, which highlight the work of students, staff and faculty.

“We thought the award was a really great way to honor her and recognize individuals who are championing equity, diversity and inclusion here at Duke,” said Associate Professor of Medicine and School of Medicine Vice Dean for Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Dr. Kevin Thomas, who worked alongside Winn and was one of the inaugural winners of her award.

McCray didn’t know much about Winn when she found out she won the award. But after learning about Winn’s legacy, the honor has greater meaning.

“To know that what I do aligns with her work makes me very proud,” McCray said.

Send story ideas, shout-outs and photographs through our story idea form or write working@duke.edu.