'The Pivot,' a Ground-Level Look at Duke University During the Pandemic

New book by Robert Bliwise tells the stories of campus staff, students and faculty adapting to a crisis

One of the first people readers meet in Robert Bliwise’s new book on campus life at Duke during the pandemic is Valerie Williams, the manager of the Marketplace on East Campus. It was her job to oversee a pivot in dining for first-year students during the pandemic and find ways to feed more than 1,500 students several meals a day safely, generally stripped of the social connection that normally characterizes student dining.

One of the first people readers meet in Robert Bliwise’s new book on campus life at Duke during the pandemic is Valerie Williams, the manager of the Marketplace on East Campus. It was her job to oversee a pivot in dining for first-year students during the pandemic and find ways to feed more than 1,500 students several meals a day safely, generally stripped of the social connection that normally characterizes student dining.

Wearing a mask, Williams, a 44-year veteran of Duke Dining, arrived at work nearly every day during the pandemic, regularly checking in on the mental health of her staff and of the students she served. Bliwise asked Williams what kept her going during the long trying days of the pandemic. “Seeing people happy,” she responded.

In “The Pivot: One Pandemic, One University” (Duke University Press), Bliwise puts pandemic profiles such as Williams, bus driver Michael Eubanks, and numerous faculty members, staff and administrators at the heart of the story of Duke’s trials during the crisis. While the university received national attention for how its testing program and safety protocols kept the campus community running during the crisis, Bliwise said he wanted to tell the lesser-known stories of the people on the ground who made it happen, from the Learning Innovation team that guided faculty as courses moved into virtual space, to admissions officers operating in an environment where recruiting visits were off-limits, to healthcare workers coping with all the unknowns attached to COVID-19.

Their collective efforts, he said, showed that higher education, often characterized as slow to change, can be nimble.

“I wanted to speak to an audience beyond Duke,” said Bliwise, who recently stepped down after nearly 40 years of editing the highly regarded Duke Magazine. “It struck me that by telling the story at the ground level would make for a more authentic, compelling and richer story. I was less interested in the policy discussions than in how the policies played out and shaped campus life.

“It took me to places on the campus I didn’t generally write about in my old routine at the magazine. Spending several hours with Valerie Williams and seeing the care she took and the pride she had in feeding the students and working under pandemic conditions, it brought home how she and others were vital players in keeping this place going.”

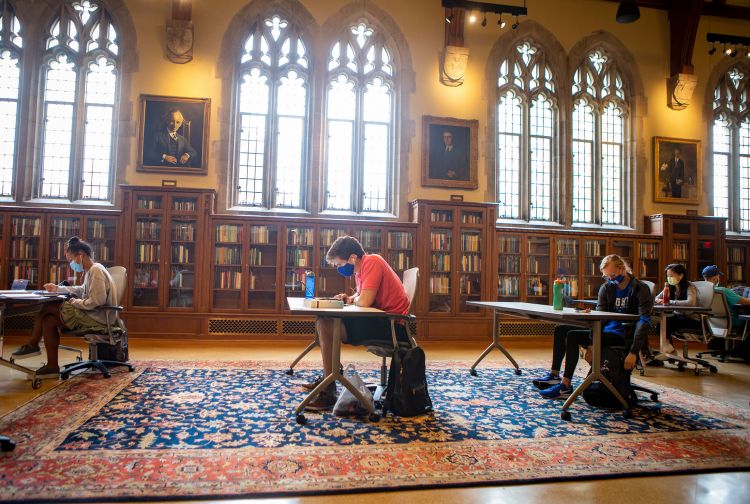

His reporting takes him into Zoom classes across the undergraduate curriculum, where some faculty who previously had banned computers from their classes were adjusting to teaching through them. He explores student life from the isolation of quarantine to the challenges of sharing meals with friends at a distance. And he checked in with staff responsible for making the safety protocols work, such as the C-Team who walked around campus offering encouragement to students and caution to those violating the pandemic rules.

His reporting takes him into Zoom classes across the undergraduate curriculum, where some faculty who previously had banned computers from their classes were adjusting to teaching through them. He explores student life from the isolation of quarantine to the challenges of sharing meals with friends at a distance. And he checked in with staff responsible for making the safety protocols work, such as the C-Team who walked around campus offering encouragement to students and caution to those violating the pandemic rules.

Bliwise said his reporting reinforced some long-held ideas, in particular the essential value and necessity of in-person education. While he gives numerous examples of faculty creatively designing online classes and using the experience to rethink the core of classroom learning, his conclusion is straightforward: “Nothing can replace the experience of in-person education,” he said. “Online learning has traditionally struck me as a less than fully authentic way to enjoy the life of the classroom, and if anything that impression was solidified.”

But the pandemic brought new lessons as well that will continue to shape undergraduate education at Duke. In his book, Bliwise gives heavy attention to the pandemic’s toll on mental health and to efforts—both individual and institutional—to support emotional well-being. After hearing from many students who for the first time in their lives were struggling with isolation and online learning, he spends much of the book exploring what it means to care for students.

“One thing we all learned from living online was that students are whole people, they’re not just classroom learners,” Bliwise said. “That seems intuitive but the lesson came sharply home during the pandemic. Even those faculty who previously saw their role as being more traditionally professorial have become more deeply engaged with caring for their students and seeing their students not just as classroom learners, but as whole, complicated and somewhat vulnerable individuals.”

Bliwise said his reporting also reinforced for him the importance of campus ritual to the student experience, from the traditional class photo for first-year students to Last Day of Class celebrations. The pandemic reinforced that these events aren’t just frivolous campus customs, but an important part of the university experience.

Bliwise said his reporting also reinforced for him the importance of campus ritual to the student experience, from the traditional class photo for first-year students to Last Day of Class celebrations. The pandemic reinforced that these events aren’t just frivolous campus customs, but an important part of the university experience.

“We all had some understanding that campus life embraces a lot beyond the classroom. But the fact that for so long the community was deprived of these rituals made us confront just how embedded they are in campus life.

“They’re not just some nice asides to campus life. They are basic, elemental and essential to that shared sense of the campus, integrating people into a community and creating a particular identity. ‘Campus community’ is an expression that we use so often, but what this project taught me was that term has a lot of meaning and significance and complexity to it.

“The class photo is a perfect example. At first blush it seems to be a thoroughly incidental gesture, but after the isolation of the pandemic, you see that the gathering that is part of the class photo is a serious aspect of community bonding. And when it goes away, it’s a genuine loss.”

Faced with the same pandemic isolation as the rest of us, Bliwise said he found the opportunity to write about the period was “exhilarating,” providing an opportunity to spend the period practicing his passion of long-form reporting on a story of interest to a readership beyond Duke.

“The project allowed me to add texture, depth and complications with a range of characters and campus settings. I might reach for those qualities in Duke Magazine storytelling, though, of course, with a necessarily tighter focus and a limited—if still generous—word count. This project was one extended playground for me. It allowed me to dwell on a timely subject while leaning a lot on my own experiences and exercising my own voice. That really gets to one of my aims—documenting a consequential moment for higher education, and doing so in a way that feels original, immediate and engaging.”

Bliwise isn’t quite finished with the project. For the university’s Thompson Writing Program, he’ll be teaching a seminar next semester for first-year students called “Decoding Duke,” which will include reflections on the pandemic-time campus.