Young Minds Study the Brain at Duke

Local high schoolers participated in a full-time neuroscience research program on campus this summer

DURHAM, NC – This summer, the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences (DIBS) hosted seven local high school students to tackle some of the most puzzling and pressing research questions in neuroscience: How can we treat rare genetic brain diseases? Why are women more likely to suffer from migraines than men? How do our eyes develop?

The Duke University Neuroscience Experience (DUNE) is a summer mentorship program that pairs graduate students and postdoctoral researchers with inquisitive high schoolers, and provides them with hands-on research experience and professional development training five days a week, 9 -5.

One scholar, Karina, a rising senior from Durham intent on being the first in her family to go to college, fell in love with neuroscience after taking a psychology course her freshman year of high school. After learning about DUNE from her Scholars to College counselor at the Emily K Center, Karina was thrilled to hear that she’d been selected as one of the seven students from a pool of nearly 100 applicants.

Once a student is accepted to the program, they rank the labs they hope to be matched with.

Karina was fortunate to land her first choice and work in the lab of Duke pediatric pulmonologist and researcher Mai ElMallah MD to study new potential treatments for people with Pompe disease, a rare genetic disorder that erodes muscle tissue throughout the body.

Karina was fortunate to land her first choice and work in the lab of Duke pediatric pulmonologist and researcher Mai ElMallah MD to study new potential treatments for people with Pompe disease, a rare genetic disorder that erodes muscle tissue throughout the body.

“Usually when I think of diseases related to the brain, I only think about mental illness,” Karina said. “This lab was new and different to me because they were looking at the neuromuscular side of things, and I thought that was pretty interesting.”

For her project, Karina evaluated two different gene therapies for mice with Pompe disease. By counting cells across a collection of microscope images, Karina found that the gene therapies she administered helped mice regain neuromuscular junction cells in their diaphragm, which are critical conduits for the nervous system to talk with the muscle tissue to coordinate breathing.

While tiring, Karina says lab work is much more fun and mentally stimulating than her regular job during the school year at a fast-food restaurant, which she described as “not very interesting”. “You’re just there doing whatever needs to be done,” Karina said. “But here, [at Duke], you learn.”

Only in its second year, DUNE was started by neuroscience graduate students and postdoctoral researchers, with the goal of increasing participation of students from underrepresented groups in science. Their application pool reflects that mission, as two-thirds of applicants were women, and 85% of applicants identified as non-white – demographics that are generally less likely to pursue a degree or career in science.

DUNE is made possible by a patchwork of philanthropic donations. While the mentors and organizers are all volunteers, high schoolers are paid a stipend for their participation, which is generously provided by George Lamb, a Texas lawyer who serves as an external advisory board member for DIBS.

Kathryn Walder, a Duke alumnus and current postdoctoral researcher at Duke, also helped finance the program this year.

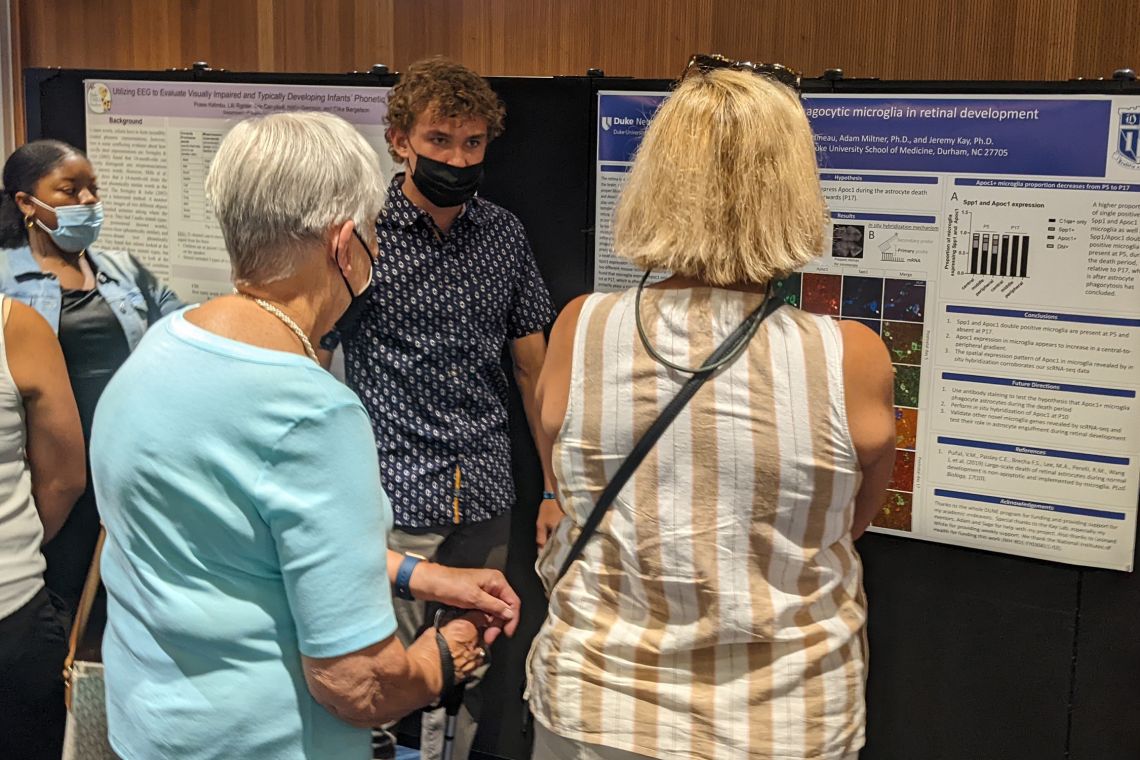

The eight-week program culminates with a research poster presentation and celebration, where students get to share what they’ve been working on over the summer with friends, family, and members of the Duke community.

Students participating in the DUNE program don’t just learn how to do research, though. They also partake in college preparation workshops, learn how to design experiments, and expand their understanding of what it means to be a scientist.

Dillon, a 17-year-old DUNE scholar from Hillsborough, NC, experienced firsthand the inherent frustrations of doing research in the lab of Duke professor of ophthalmology Jeremy Kay PhD this summer.

“It was definitely a learning curve for me because I found out the hard way that sometimes things don't always work,” Dillon said.

Despite experiments not going as planned, Dillon, like many of the DUNE scholars, relished their time at Duke this summer.

“I knew I was going to like research, but I didn't think I was going to like it this much,” Dillon said. “I wake up and I'm excited to come here in the morning and just get to work on my project, hoping things are going to work out.”