This summer, a museum in Italy is displaying the results of a six-year archaeological excavation conducted by more than 20 Duke faculty and students.

The exhibit, which opened recently at the Museo delle Antichita Etrusche e Italiche at Sapienza University in Rome, displays findings from Vulci, an Etruscan and Roman archaeological site in Viterbo, Italy.

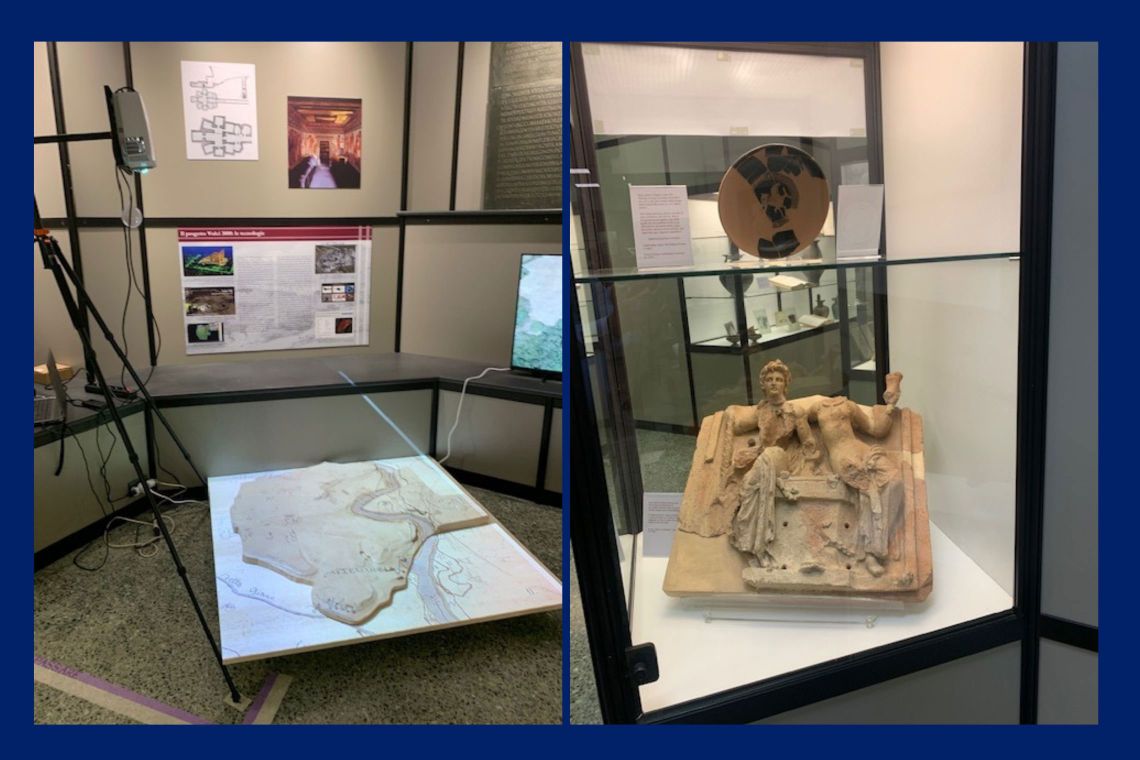

The summer project, a partnership with Sapienza University researchers, leans heavily on virtual reality and digital tools, and the exhibition includes interactive installations, including two virtual reality exhibits that reproduce the actual archaeological excavations.

The annual summer project is supervised by Maurizio Forte, a Duke professor of classical studies and art, art history and visual studies. Here, Forte speaks to Duke Today about the project.

What exactly do the digital installations show? Are they interactive?

What exactly do the digital installations show? Are they interactive?

FORTE: In the exhibition there are four digital installations: Three installations are interactive; two virtual reality installations reproducing the archaeological excavations and one AR (augmented reality) installation dedicated to the visualization of Etruscan and Roman artifacts. However, the most innovative installation is a 3D print of the archaeological landscape where it is possible to video-project several historical and digital maps of the site.

The 3D print was produced by high resolution digital terrain models of the landscape made by multispectral and LIDAR drones. It is the first experiment of this kind in archaeology. The technological collaboration with the American Sensefly, which provided the multispectral drones, made this realization successful. The AR installation is a Z-Space workstation. In this case it is possible to manipulate 3D artifacts with a 3D stylus and tracking-VR glasses.

What were you able to discover that would not have been possible without the technology you use?

FORTE: Only a little portion of the archaeological site of Vulci was excavated. We estimate that only 5% of archaeological remains are visible to the public. The rest of the city was revealed mainly by geophysical prospections, LIDAR and multispectral flights by drone technology. In short, without remote sensing technologies we would have a minimal knowledge of the entire site.

In particular, two Duke PhD students in Classical Studies and Visual Studies, Antonio LoPiano and Katie McCusker (now Dr. McCusker) contributed to create a very new digital map of the site, in 2D and 3D, available also in GIS and virtual reality. All these scientific data will be available also in a manageable format for the general public, so park visitors will experience the hidden city of Vulci (still in the underground) in different forms of visualization.

How has the digital installation of VR/AR applications changed and challenged the field of archeology? And what is considered traditional excavation?

FORTE: VR/AR are important tools because they are considered metamedia information in archaeology: They go beyond the traditional media and they have a different cognitive impact in the human brain. This is particularly important in the communication process. We have reconstructed in VR all the phases of excavation, so we can simulate the entire archaeological excavation since the beginning on scale and through immersive systems. Traditional (and past) excavations were suffering from a lack of accurate documentation, especially in three dimensions.

How has this excavation changed you as an archeologist and how you see this excavation?

FORTE: This excavation changed my research perspectives in urban classical archaeology – 1,500 years of urban occupation of the same site with an unbelievable level of density of buildings, infrastructures, ritual and public activities. I started to rethink the definition of city in the pre-Roman and Roman colonial world, its formation process and cultural identity

How has the excavation shined more light on the history of Vulci?

FORTE: The Duke excavation, started in 2016, was the first to dig stratigraphically and with new methods of investigation the urban area of the site. Thanks to this approach we discovered a series of important Roman public buildings overlapping earlier Etruscan infrastructures. In particular we are still investigating a very complex network of pipes, channels, cuniculi and water infrastructures from the Etruscan to the Roman period.

Moreover, we reconstruct a very articulated urban historical sequence from the 6th BCE to the 5th CE. It is interesting to note that the same area was destined to ritual activities in Etruscan and Roman times.