Onyema Nwanaji-Enwerem says early experiences with illness, death and health inequities in the predominantly African American community in Concord, North Carolina, where he grew up, drove him to become a doctor.

Frequently, he would meet a relative or respected community member, and then a short time later, hear tragic news about how their life was drastically altered or even cut short due to medical conditions they might have avoided through better-managed health care.

“We witnessed neighbors and friends who had premature deaths or really adverse health outcomes from preventable diseases,” Nwanaji-Enwerem said. “It was constantly seeing the impact it had on my family and the community that made me want to serve in that capacity.”

He also recalls a transformative moment during a trip to his parents’ home country of Nigeria when he was a high schooler. While traveling by road, his family came upon a bus that had overturned after running over a hazard. Several passengers were lying on the road in grave condition, he said.

“In the U.S., when there’s an accident you see on the street or the roadside, you immediately hear sirens and you know help is on the way,” Nwanaji-Enwerem said. “Here, there was nothing. I’m sure several of them didn’t make it past that day.”

The surreal and grim scene spurred Nwanaji-Enwerem, then only a teenager, to think about disparate access to health care and medical infrastructure around the world – and the ways he might be able to help.

The surreal and grim scene spurred Nwanaji-Enwerem, then only a teenager, to think about disparate access to health care and medical infrastructure around the world – and the ways he might be able to help.

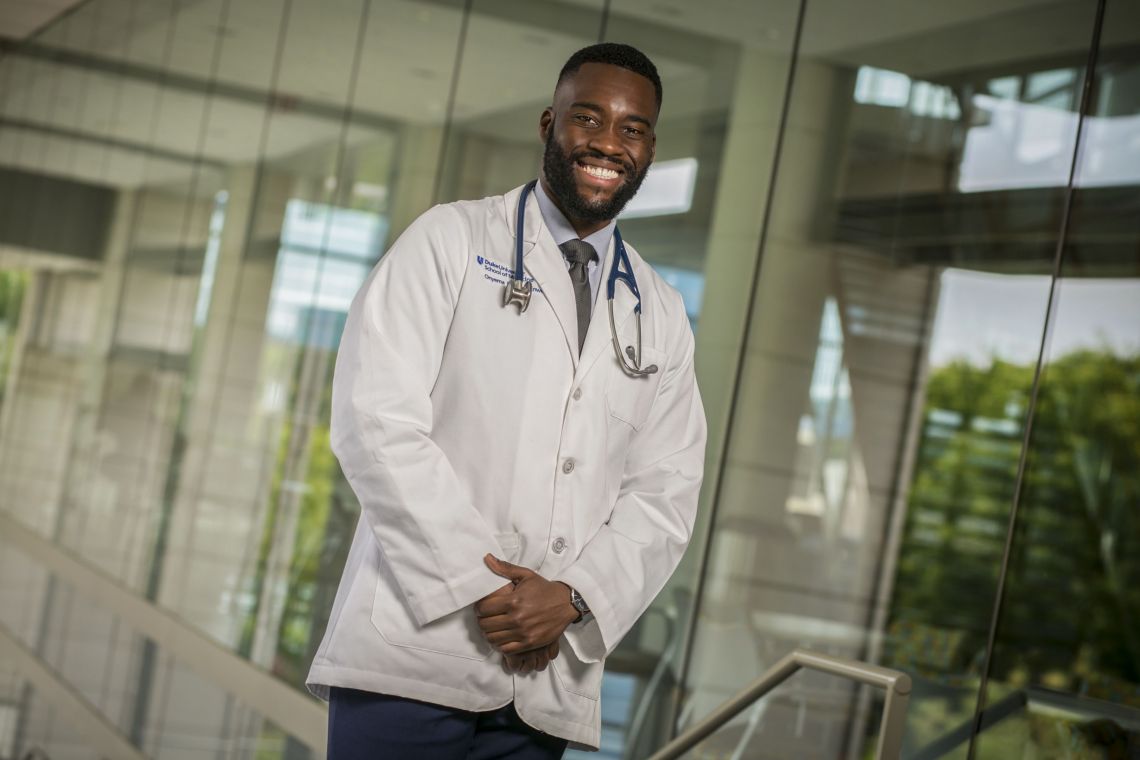

He is graduating with his M.D. from Duke’s School of Medicine, which is the final piece of a dual degree (Nwanaji-Enwerem earned a master’s in public policy from Harvard University last year).

It’s also the beginning of another chapter at Duke, and one in which he’ll have a direct impact on the community. Following commencement, Nwanaji-Enwerem will keep his knowledge and skills at Duke, launching a three-year residency with the school's Department of Family Medicine and Community Health. The beauty of family medicine is that providers get to see everyone, from babies to elder adults, he said.

“I found that I was happiest when I was thinking not only about a one-on-one interaction I was having with a patient, but also getting a glimpse into people’s lives and understanding what a community is experiencing over time,” Nwanaji-Enwerem said.

He will follow the residency with a three-year stint in the National Health Service Corps, a federal program that will place him in a high-needs community somewhere in the U.S.

Long term, he hopes to combine his passions as a physician and advocate to influence health policy – to be a doctor who “has a listening ear towards the community and who understands what is driving certain outcomes.”

Being that doctor and advocate can come in different forms.

“It’s a blend of patient care, policy and advocacy,” he said. “It’s hard to know exactly what that looks like.”

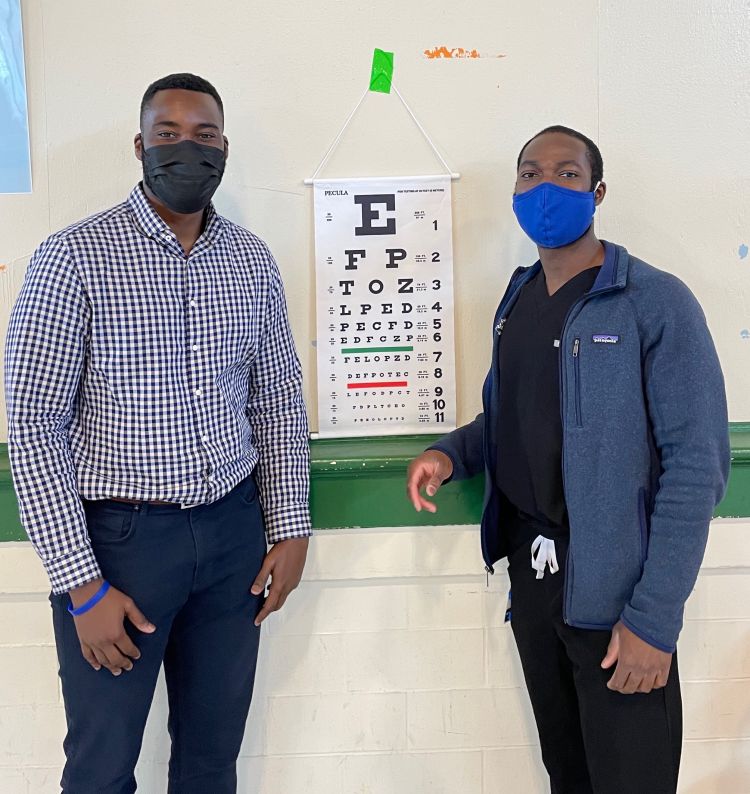

Perhaps it looks a bit like the snapshots Nwanaji-Enwerem shared from a recent visit to Merrick-Moore Elementary in Durham, where he and fellow Duke M.D. graduate Dennis Akrobetu offered free vision screenings to first graders. When the 96 children weren’t taking turns reciting what they saw on an eye chart, they tried on decorative eye patches and smiled proudly for selfies with the newly minted Duke docs.

“Even small community engagement programs, or volunteering with kids at an elementary school – that’s one more method of being involved and understanding what it is the community needs,” Nwanaji-Enwerem said.