DURHAM, N.C. – Curious about why some people have been so passionately, often angrily, opposed to vaccination against the COVID-19 virus, a team of researchers with access to rare and unusual insights into the childhood forces that shape our adult lives thought they’d try to find out.

“We had so many friends and family who initially said that the pandemic was a hoax, and then refused to wear a mask or social-distance, and kept singing in the choir and attending events,” said Terrie Moffitt, the senior author on a new study that appeared March 24 in PNAS Nexus, a new open access journal.

“And then when the vaccines came along, they said ‘over their dead bodies,’ they would certainly not get them,” said Moffitt, who is the Nannerl O. Keohane University Distinguished Professor of Psychology & Neuroscience at Duke University. “These beliefs seem to be very passionate and deeply held, and close to the bone. So we wanted to know where they came from.”

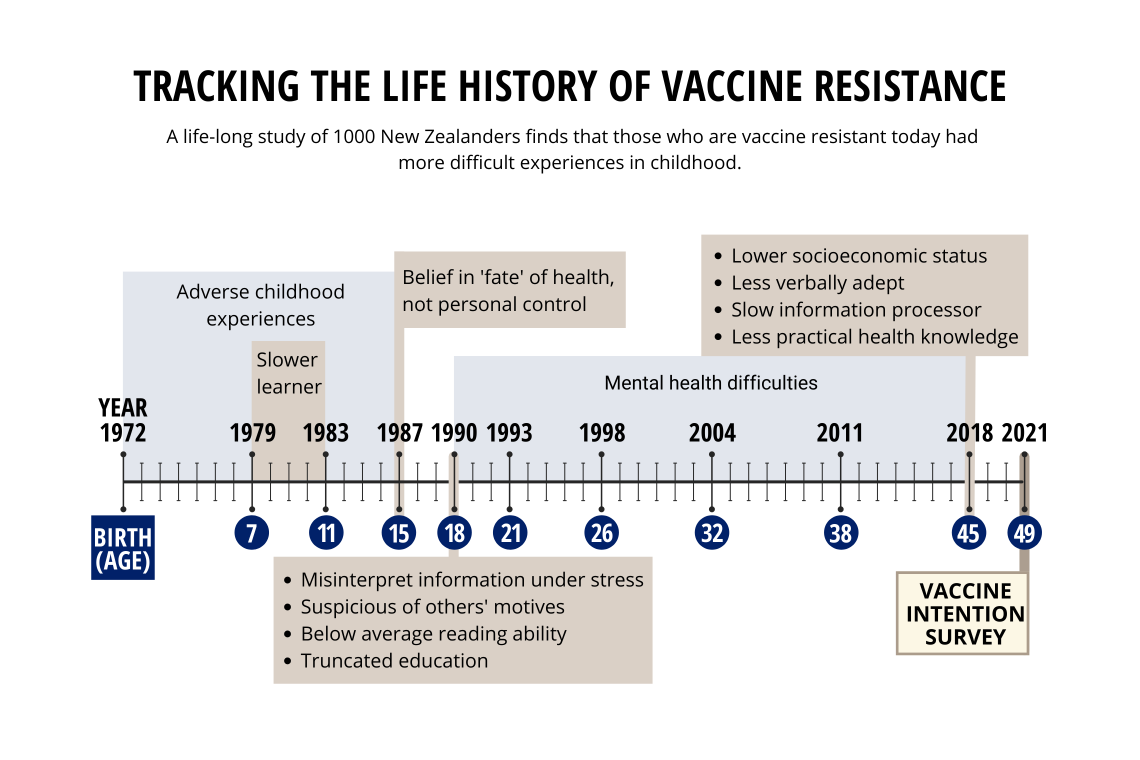

The researchers turned to their database, the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, which has been tracking all of the nearly 1,000 people born in 1972 and 1973 in a single town in New Zealand. Since childhood, the researchers have measured multiple social, psychological and health factors in each of the participants’ lives, resulting in a steady stream of research publications offering deep insights into how childhood and its environment forms the adult.

They ran a special survey of their participants in the middle of 2021 to gauge vaccination intentions shortly before the vaccines became available in New Zealand. Then they matched each individual’s responses to what they know about that person’s upbringing and personality style.

The Gallup organization estimated last year that about one in five Americans was vaccine resistant. The Dunedin data showed that 40 years ago in childhood, many of the participants who said they were now vaccine-resistant or hesitant had adverse childhood experiences, including abuse, neglect, threats, and deprivations.

“That suggests to us that they learned from a tender age ‘don't trust the grownups,’” Moffitt said. “If anyone comes on to you with authority, they're just trying to get something, and they don’t care about you, they’ll take advantage. That's what they learned in childhood, from their experiences growing up at home. And that kind of learning at that age leaves you with a sort of a legacy of mistrust. It's so deep-seated that it automatically brings up extreme emotions.”

The survey also showed that “the mistrust was widespread, extending not only to institutions and influencers, but also to family, friends and co-workers,” according to the paper.

“You just think of what a long shadow that casts,” said co-author Stacy Wood, the Langdon Distinguished University Professor of Marketing at North Carolina State University. “If your trust is abused as a child, later on, four decades later, you still don’t trust. That’s not trivial. I’m not going to get around that with a cool campaign or a celebrity endorser.”

At ages 13 and 15, the vaccine-resistant group had tended to believe that their health was a matter of external factors beyond their control.

At age 18, the teens who became the vaccine-resistant and hesitant groups also were more likely to shut down under stress, more alienated, more aggressive. They also tended to value personal freedom over social norms, and being nonconformist.

The resistant and hesitant groups had scored lower on mental processing speed, reading level, and verbal ability as children. At age 45, before the pandemic, these people were also found to have less practical everyday health knowledge, which suggests they may have been less well-equipped to make health decisions in the stress of the pandemic. None of these observations changed when the survey findings were controlled for the participants’ socioeconomic status.

Wood, a marketing professor who specializes in health messages, said many healthcare workers who have been pouring their hearts into fighting the pandemic have taken resistance to vaccines personally and literally cannot comprehend why patients refuse so adamantly. “Doctors and hospitals have been asking us ‘Why would people be so resistant? Why can’t we convince them with data?’”

Unfortunately, Wood said, the fear and uncertainty of the pandemic triggers a fight to survive in some of these people, an ancient response that reaches back decades in their past and is grounded firmly in their own sense of self. “The root of this is, you can’t change this as a healthcare provider,” Wood said. “And it’s not about you. It’s not a diminution of your service and your warm intent.”

Moffitt points out that this study is limited by the fact that it’s a self-report of vaccine intentions from just one group of people and that any reappraisal of health policy should include data from many countries. However, the researchers do have some ideas about how to use this knowledge.

“The best investments we could make now would be in building children’s trust and building stable environments, and ensuring that if the individual caregiver fails them, society will take care of them,” Wood said.

“Preparing for the next pandemic has to begin with today's children,” said co-author Avshalom Caspi, the Edward M. Arnett Distinguished Professor of Psychology & Neuroscience at Duke. “This isn’t a contemporaneous problem. You can't combat the hesitancy and the reluctance with adults who have been growing up to resist it their entire lives.”

“It’s also the case that pro-vaccination messaging is not operating in a vacuum,” Moffitt added. “It’s competing against the anti-vax messaging on social media. The anti-vaxxers are winding people up with mistrust and fear and anger. It creates a situation where their audience is very distressed and upset and then can't think clearly. They're manipulating emotions, which reduces cognitive processing.”

This research was supported by US National Institute on Aging grant AG032282, UK Medical Research Council grant MR/P005918/1, the Duke Center for Population Health and Aging P30 AG034424, and by the American Psychological Association and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Award # 6NU87PS004366-03-02). The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Research Unit is supported by the New Zealand Health Research Council Programme Grant (16-604), and the New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE).

CITATION: “Deep-Seated Psychological Histories of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitance and Resistance,” Terrie Moffitt, Avshalom Caspi, Anthony Ambler, Kyle Bourassa, HonaLee Harrington, Sean Hogan, Renate Houts, Sandhya Ramrakha, Stacy Wood, Richie Poulton. PNAS Nexus, March 24, 2022. DOI: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgac034