Neither War Nor Quick Solution Expected in Russia-Ukraine Standoff, Experts Say

Duke faculty share insights with media

While Russian President Vladimir Putin probably won’t start an all-out war, he’s also unlikely to be intimidated by sanctions threatened by NATO and the United States – complicating the ongoing crisis at the Ukraine border, three Duke scholars said Wednesday.

Speaking to journalists in a virtual media briefing, the three experts discussed sanctions, concessions, the U.S.’s role, Putin’s role and the Russian people’s view of the ongoing threat. (Watch the briefing on YouTube.)

Here are excerpts:

ON CONCESSIONS THE US AND NATO MIGHT MAKE

Simon Miles, public policy professor, expert on Russia and former Soviet Union

“What concessions should be made, and what concessions might be made? Those are two different things from an American policy standpoint. It’s pretty clear, for example, from some of the public statements coming out of Moscow, that if NATO were to pack up its toys and go home from eastern Europe, that would be welcome. Whether or not that would actually put an end to some of the foreign policy problems is a different question and I don’t think the United States should put things like precluding NATO expansion on the table.”

“I think what we would probably see some productive conversations taking place around are issues like missile defense, intermediate range and theater-range nuclear forces in Europe and in general the positioning of missiles in Europe. Probably also to do with military exercises, which might actually be a backdoor into talking about a reduction in the quantity of troops in eastern Europe, because that quantity waxes and wanes primarily through exercises.”

ON WHETHER SANCTIONS ON RUSSIA WOULD WORK

Bruce Jentleson, professor of public policy and political science, former senior adviser, U.S. State Department

“If you look at the economic arsenal, you say, ‘Well, we really got a lot of things. We could cut them off from the international financial system through the dominance of the dollar in it. We can invoke all sorts of … secondary sanctions, which are not just on U.S. trade. Anyone using American-made parts or American-licensed technology around the world, semi-conductors and the like, we can target Putin and his cronies.”

“The problem is, if you look at military strategy, you look at what’s my offense and what’s the other guy’s defense. There’s not enough being done right now about that in relation to sanctions – what are the Russian counter-strategies?”

“Sanctions have never crippled; they can impose economic cost. But there are a couple counter-strategies we need to pay attention to on these with Russia.”

“One obviously is Europe, which is getting a lot of attention. Both the Biden administration and much of the talk in the media kind of disparages Europe: ‘Why aren’t you as tough as us,’ and all those sorts of things. It’s worth bearing in mind that European trade with Russia is 11 times greater than ours. They get a significant chunk of their oil and natural gas from Russia.”

“They have more at stake there. It’s worth asking ourselves, if it’s reversed, would we pay that economic cost?”

“There’s China. Russia-Chinese trade has grown. I think it’s $146 billion now. China has a payment system that can help ease the pain of what we can do on finance.”

“China can help not totally offset the sanctions, but compensate.”

ON WHETHER RUSSIA WILL ACTUALLY LAUNCH A MAJOR MILITARY INVASION OF UKRAINE

Charles Dunlap, law professor, retired major general, U.S. Air Force

“I don’t think Putin will do that. I think he’s already achieved many of his strategic gains. He’s crushed any illusions that Ukrainians might have had that any nation on planet earth would come to their aid in terms of putting troops on the ground. That will have a significant psychological effect on the Ukrainian people and a reverberating effect, quite frankly, on even NATO allies in eastern Europe.”

“The reality is, a couple planeloads of U.S. military equipment aren’t going to turn the Ukrainian military into something that can actually counter or deter Russian military effort. And I don’t think Ukraine could ever get there. They just don’t have the resources or the economy to build something to truly counter what Russia can do.”

“While Putin might not have gotten the explicit agreement to bar the Ukraine forever from joining NATO, I think de facto he’s achieved it. The NATO countries are so rattled by the idea that there might actually be war over this, that any effort to have Ukraine join NATO won’t gain traction in the foreseeable future.”

“He’s demonstrated something that maybe the world hasn’t truly recognized, which is just how formidable the Russian military has become. The is not the Russian military of 10 years ago, when soldiers were unpaid. It has high-tech weapons; they’re well trained. They’re not as large as the combined efforts of NATO, but I do think it can take on individual NATO countries quite well. The question is how much NATO is truly prepared to meet this kind of Russian threat.”

“It also illustrates the vulnerability of NATO countries – the 40 percent of their gas that comes from Russia.”

ON PUTIN’S LEGACY

Simon Miles

“For a man like Vladimir Putin, his argument for why he should be in charge of that country … is that only a strong leader like him can run a country made up of people like Russians. This has been a constant refrain, basically since he took power.”

“That’s a tougher argument to make if you have, right on your borders, a country of people who are allegedly, by your own words, the same people, and it’s a prosperous, western-oriented market democracy. That really is a challenge for Putin on the domestic front, this idea of a Ukraine that is aligned with the west and is prosperous and successful.”

“He also certainly is aware of his age. The deal that got him in place to replace Boris Yeltsin, who was the first president of Russia, was a pretty simple one. He told Yeltsin, ‘If you let me take over I will make sure no one can harm you.’ And at that point in the early 2000s, it was a very long, long list of people who had it out for Yeltsin.”

“There is no one in Russia today who can make that deal with Vladimir Putin. There is no one in Russia today who can credibly assure him of a safe, comfortable retirement. And I should emphasize the ‘comfortable’ part because he has amassed a pretty significant fortune and I imagine he is looking forward to benefitting from it.”

“So I think this is a legacy issue for him. I think he sees Ukraine as a bone in Russia’s throat right now as far as completing Russia’s foreign policy goals, which really is to leave it in a position of maximum leverage and maximum autonomy.”

“We see the amount of resources that are being devoted to this effort, diplomatic and also scarce military resources which are being devoted to this effort. I think he sees this uniquely tied up to with his legacy, the legacy he’s going to bequeath to Russia when he does leave office.”

ON THE US MOVING TROOPS INTO EASTERN EUROPE

Charles Dunlap

“I think it’s largely symbolic and I think there’s zero chance those troops would be used inside the Ukraine. I think it’s mainly to bolster the confidence of our NATO partners on the eastern front there. In Poland and so forth. It is too small a number. We do have the best paratroopers on the planet, but 3,500 paratroopers are not going to stop 135,000 Russian troops. So I think it’s a symbol. I’m not particularly in favor of using military forces that way to try to send messages. If you’re going to send a message, you don’t do it with 3,500 troops.”

“It really is a diplomatic move to show the Poles, for example, that if Russia does do something, there are American troops on the ground. Those troops would defend Poland as part of a NATO action.”

“But it doesn’t do much for the Ukrainians in my view.”

ON THE VIEW FROM WITHIN RUSSIA

Simon Miles

“A huge proportion of the Russian population is just not interested in this. Countless Russians turn their TVs off right now when the news … shifts to Ukraine, as opposed to continuing to watch it.”

“They’re not interested in what’s going on. This is not an issue that is animating them. They’re really interested in some domestic, economic welfare questions, not in what’s going on in Ukraine.”

“While Putin certainly does derive domestic political benefit from showing strength … he also derives a lot of benefit from showing wisdom, what we could call kind of an elder statesman role. So there is undeniably a way the Russians could spin this .. to say, ‘Look, these American Chicken Littles are freaking out just because we’re having totally normal military exercises.’”

“Putin can really use this, I think, to play this senior figure, this steady hand on the tiller -- which is his argument to Russians about the value of his leadership.”

ON STABILIZATION AFTER AN INVASION

Bruce Jentleson

“Destabilization is one thing. That’s what Putin has been doing since 2014 in Ukraine. Becoming responsible for stabilization is a much more difficult objective militarily, economically, diplomatically. We found that out in Afghanistan, we found out in Iraq.”

“Stabilization is a very different task. To that extent, the ways in which we’ve been providing some aid to the Ukrainians, I think, is OK. The greatest deterrent to Putin is the sense of the costs of invading, the day after. All sorts of things can happen that first week. He won’t do like our president did and say ‘Mission Accomplished’ too early. But I think that’s the greatest deterrent. So all of these things make a mix where the strategy for the Biden administration should be to keep their eye on the goals here and not necessarily making sure we’re at the center and get credit for whatever’s achieved. Let’s share some of that credit in ways that could, conceivably, achieve objectives that serve our interests as well.”

ON RUSSIA’S DISINTEREST IN OCCUPATION

Simon Miles

“No Russian policymaker that I have ever heard of feels that (recent Russian occupations in Ukraine) those went well. And those are kind of best-case scenario occupations. You have maximum cultural, social overlap with your partners. You’re working from a pretty broad set of similar assumptions. If you look at, for example, how the Russians have comported themselves in Donetsk and Luhansk, this has obviously been militarily successful, but no one, I think, in Moscow is saying, ‘Let’s do this again, but bigger.’ Ditto on annexed Crimea.”

“I do think there’s a lot of sense in Russia … that occupation in Ukraine, even in a very limited scale, has not been an experience anyone wants to repeat.”

ON RECENT RUSSIAN MILITARY EXERCISES NEAR UKRAINE

Charles Dunlap

“There is enormous military value to what the Russians have done in terms of exercise and their ability to move forces. It is extremely complicated, what they did, and it is something we need to take notice of – that they’re able to do it.”

“They have moved key forces from the Far East and while there’s this seeming rapprochement with China, I think Russian military strategists are well aware they need to get those troops back there. They do not want to leave that area with less than (forces) to defend it.”

“The U.S. approach here, I think it should be something of a wakeup call. The U.S. also needs to think strategically because other countries in the world are looking at this. If you’re in Taiwan and you see what’s happening in Ukraine, that could be a wakeup call. In other words, nobody is coming to help them. If you’re in Saudi Arabia and you’re looking at the Iranian threat, you might wonder who would help them if the Iranians, you know, tried to intimidate them or even militarily be aggressive. I wonder, strategically speaking, if we’re going to see some proliferation of nuclear weapons.”

“So it would be a mistake, I think, for the U.S. to look at this situation in isolation from other situations around the world. The diplomatic effort has to be conscious of the implications for this particular crisis with other countries in other parts of the world.”

“I do think given the circumstances, I think the Biden administration has used the options they have and I think it has been and should be a wakeup call to realize how complicated it is and maybe how limited the options are when you are confronted by this sort of crisis.”

ON WHETHER NATO IS WEAKENED NOW

Charles Dunlap

“I think NATO has to do some re-thinking because … it may be that this could serve as a wakeup call for them. It may have been in Europe that they really didn’t think that Russia would present his kind of a military threat. That may be part of the reason they haven’t met the 2 percent (shared defense spending) or done everything maybe they should do, especially in Germany, to have military forces as capable as they should be.”

“I don’t think that NATO is particularly weakened. I think that NATO wasn’t as strong as we wanted to believe it was in the first place. I do think NATO has a lot of work to do and this should be something of a wakeup call for them.”

ON HOW THIS ALL ENDS

Simon Miles

“We’re not going to see a dramatic breakthrough. I don’t think you’re going to see a great, made-for-TV moment of the Russian and American negotiators bursting out of some room in Geneva brandishing a piece of paper and saying, ‘Hey, we did it. We struck a deal.’ ”

“The reason for that is really basically that certainly the Russian diplomats who are engaging … are not really empowered by Putin to negotiate. They’re there to deliver talking points, statements of the Russian point of view.”

“This is going to be slow. This is going to be drawn out, simply because Russian diplomats are not really empowered to make any meaningful concessions. They’re there to be the intermediaries.”

“These big breakthrough moments are few and far between. A lot of this is just hard work, long hours grinding out these types of bargains.”

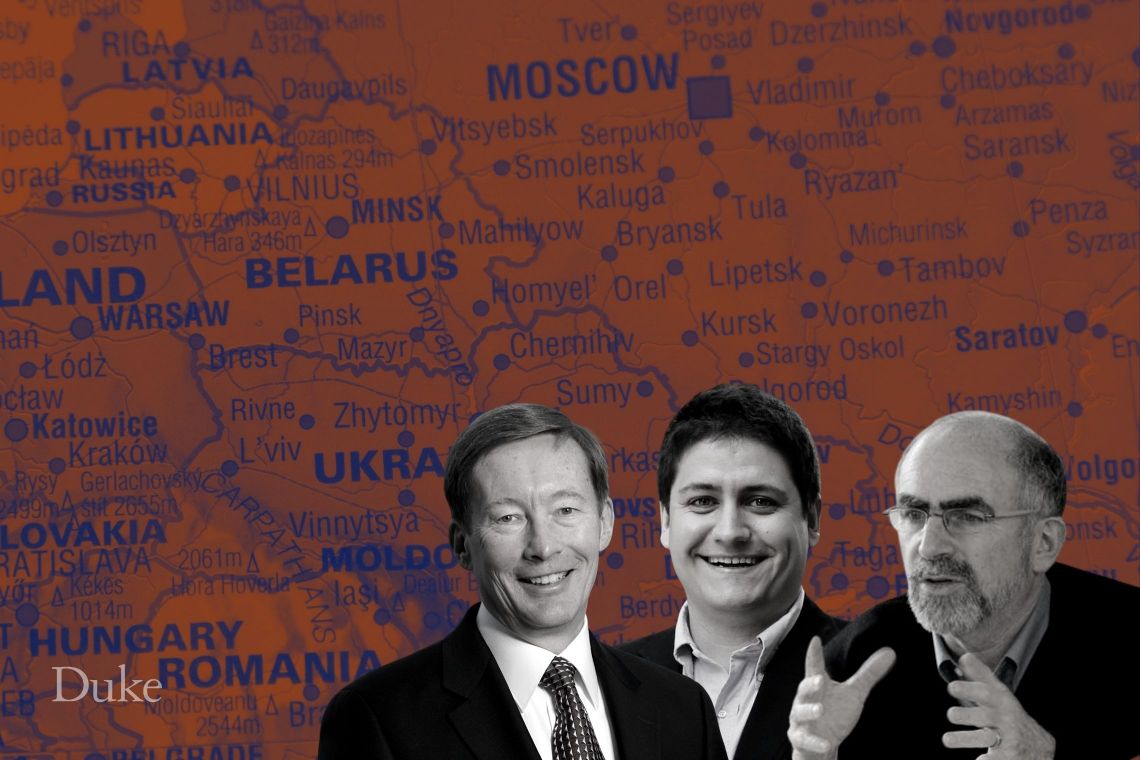

Faculty Participants

Charles Dunlap

Charles Dunlap Jr. is a professor of the practice at Duke University's School of Law and executive director of its Center on Law, Ethics & National Security. Dunlap retired from the U.S. Air Force in June 2010 as a major general after a 34-year career in the Judge Advocate General Corps.

Bruce Jentleson

Bruce Jentleson is a professor of public policy and political science at Duke University. He served as senior adviser to the State Department Policy Planning Director from 2009-11 and is author of “The Peacemakers: Leadership Lessons from Twentieth-Century Statesmanship.”

Simon Miles

Simon Miles is an assistant professor in the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke and an expert in Russia and the former Soviet Union. He is the author of “Engaging the Evil Empire,” an account of how Washington and Moscow ended the Cold War.

_ _ _ _

Duke experts on a variety of topics can be found here.

Follow Duke News on Twitter: @DukeNews