There are many stories told about the late Lawrence Goodwyn, the sometimes cantankerous Duke historian famed as co-founder of Duke’s Oral History program and a mentor to numerous students, activists, journalists and organizers. Many stories are told with a feel of legend. This one is true.

Near the end of his life in 2008, Goodwyn, long suspicious of politicians, shed some of this cynicism to canvass on behalf of the Obama campaign. Duke Professor Gunther Peck remembers how Goodwyn, then needing an oxygen tank, for went on a long, tough day of meeting reluctant voters in a Walmart parking lot and offering them optimism about the possibility of change.

“Larry had an answer for even the most betrayed citizen he encountered,” Peck writes. “To the Black Veteran who cursed the country who made him kill ‘yellow men’ then abandoned him ‘like a piece of broken furniture,’ Larry simply listened. This was Larry’s most powerful answer: respectful silence and providing a moral witness to his anger and betrayal. After a beautiful pause, Larry broke the silence with three short words: ‘I hear you.’”

“Larry had an answer for even the most betrayed citizen he encountered,” Peck writes. “To the Black Veteran who cursed the country who made him kill ‘yellow men’ then abandoned him ‘like a piece of broken furniture,’ Larry simply listened. This was Larry’s most powerful answer: respectful silence and providing a moral witness to his anger and betrayal. After a beautiful pause, Larry broke the silence with three short words: ‘I hear you.’”

The veteran paused, at Larry and his oxygen tank, then took the form and registered to vote for the first time in his life.

Peck says that story speaks to Goodwyn’s ability to build connections with people across various boundaries. That ability informed not only his pathbreaking scholarship on American social and political movements, but also the strength of his belief in democratic values.

The story comes from “People Power,” a collection of essays from former students, colleagues and activists inspired by Goodwyn, who died in 2013. The book is edited by Wesley Hogan, former director of Duke’s Center for Documentary Studies and current research professor at the Franklin Humanities Institute, and Paul Ortiz, director of the Proctor Oral History Program at the University of Florida.

Subtitled “History, Organizing and Larry Goodwyn’s Democratic Vision in the 21st Century,” the book isn’t a festschrift. It honors Goodwyn, but the focus is more on the work done by the many people he inspired with his vision for a more just and democratic society. The range of his interest in social movements – his research spanned from 19th century US populists to the Solidarity Movement in Poland – all explored how democratic values can empower grass roots efforts to bring change.

Below, co-editors Hogan and Ortiz discuss what Goodwyn meant to them and why they believe a book exploring his values is particularly needed now.

Q: What are you looking for readers to take away from this book?

WESLEY HOGAN: His words and actions inspired our contributors, they put his ideas into action in their lives. Together, the essays present a plan for how to live democratically, something that at this particular moment feels nearly impossible given the size of multinational corporations and the rise of fascism across the globe. But the thirst for democracy is real; people want some say in the important decisions that impact their lives. To date, we don’t have so many models for democratic living. For me, it was exciting to work with so many people who are working today to live the values Larry taught us about.

In addition to providing practical tools created by 19th century social movements to create a more democratic economy, Larry grew up in Texas. He understood where white supremacy came from. He frequently noted that white Southerners engaged in racism not because they were inherently evil, but because powerful influences ensured they couldn’t see any other path. In promoting the ‘Lost Cause,’ across the generations, too many white Southerners lost their ability of critical reflection. Many literally can’t see any other way forward. “They need a new flag, a new set of captains to get behind,” he often said. It is so relevant today. Larry argued for a more democratic history that everyone could believe in, a path beyond white supremacy.

Q: In the classroom and as a mentor, what did Larry bring to students and colleagues?

HOGAN: Taking a class with Larry could be difficult. Some of the pieces in our book can be painful to read. Faulkner Fox, Elise Goldwasser, Donnel Baird, and others reflected on the reality that just because Larry understood white male privilege didn’t mean he didn’t invoke it. He could embody white privilege without irony, and that meant the class wasn’t always a smooth path. He always encouraged students to challenge him, and many did. We wanted to explore that contradictory aspect of him.

And Larry would have expected that of us. Gunther Peck found after Larry died a stash of student complaint letters in his office. It was clear that Larry had kept them to review them to become a better teacher. Some of this was part of his teaching method. One of his messages is that just because you are fighting for freedom doesn’t let you off the hook for your behavior. His insistence that he himself was part of the problem of authority was very freeing for all of his students. We would push back against him and there was a moment when we would realize that in pushing against him, he was teaching us to push against power. In his essay, Duke alum Adam Lioz (Trinity ’98) reflects on the fact that in Goodwyn's class, “I began to see how economic and political elites use racism strategically to divide and conquer, breaking apart class-based solidarity among Black, brown, and white people so they can hoard money and power--and how this has not been a side story in American political history, but rather the central plot.” He has spent rest of his life trying to fight that.

Q: What did he mean to you personally?

PAUL ORTIZ: Larry’s name comes up so often when I’m talking with other activists. You can’t talk with people engaged in social struggles or studying populist movements and not come across his work. He continues to have an incredible impact. If you are studying social change, he’s everywhere, and his influence is seen in the range of people who contributed to the book. There are so many award-winners there, so many people at the top of the field. You have people like Scott Ellsworth (prize-winning author of “The Secret Game” and of the first comprehensive history of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre) who came out of the Duke Oral History program, and you see how they’re continuing his work.

And personally, he’s had a great impact on how I do my work. He emphasized that you as a teacher are not doing your job if you are just teaching in a classroom. He said you have to get off of the campus and into the community, and that was a two-way street. You learned from the community as well. Knowledge was reciprocal. And all the students who came out of his programs have put that message into their work.

Q: What is the legacy of his belief in and support of oral history?

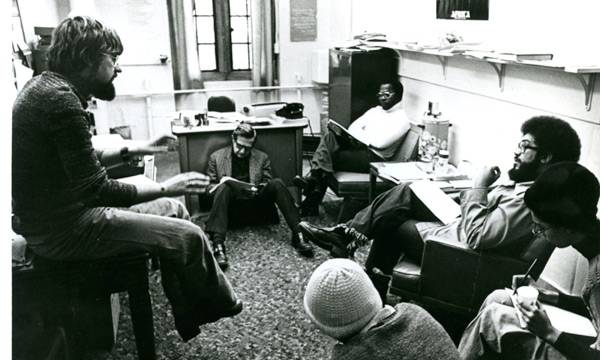

HOGAN: Larry, Ray Gavins and Bill Chafe developed the oral history program at Duke. This was the first attempt to bring Black scholars in graduate school to write on civil rights movements, and to do so in a way that emphasized the grass roots work of the movement. In the early 1970s, no predominantly white universities were prioritizing that.

Oral history is still sometimes controversial; recent incidents like the Belfast Project at Boston College illustrate the way it has not fallen under the protection of the First Amendment. In an academic context still overly influenced by Western assumptions, it has been questioned by scholars who prioritize the written document. Indigenous scholars across the globe have always contested the primacy of the written record, and within Duke’s Oral History Program, the use of oral history reset the study of the civil rights and Black Power movements over the last half-century. It brought to the forefront the stories on thousands of activists working on the ground, often at great risk to their lives, and it allows historians to unearth tremendously more accurate data on who and what made these movements. You get a much more layered, profound historical look than if you focus on the most visible leaders like Dr. King and Malcolm X. In the. end, Bill, Ray, and Larry’s creation is one of their most significant legacies, not just to the study of social movements but to historical study as a field.