That Squid Game became an international hit may have even surprised Netflix executives, but the international reach of Korean culture has been growing for a long time.

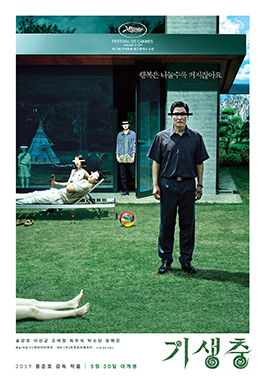

However, the gorefest of “Squid Game” is another popular example of a particular genre of Korean films and TV shows, a genre that includes Bong Joon-ho’s “Parasite” and “Snowpiercer,” and even the zombie film “Train to Busan.” Like “Squid Game,” the terror of the action in these show is matched by the trauma created by a society built on extreme class divisions and the punishment placed on the people who are losers in the system. While all cultures offer economic criticisms, Korean contributions seem to particularly catch the global imagination.

Duke Professor Nayoung Aimee Kwon is Associate Professor in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies and a scholar of Korean culture, politics and history. She said the issues of inequality raised in “Squid Game” is part of a long theme in Korea's culture going back hundreds of years. Below, Kwon discusses the history of political criticism in Korean art and the social and culture nuances that American viewers may miss while watching a giant children’s toy massacre hundreds.

Q: What might American audiences most likely to be missing when watching “Squid Game?”

NAYOUNG AIMEE KWON: South Korean directors do not always coddle global audiences and translate everything. There are many Easter eggs that audiences may not be privy to. The gigantic doll in the "Green Light Red Light" game, is actually a ubiquitous image of a girl character that appears in school textbook lessons. Her name is Younghi and her boy counterpart is Chulsoo, common names like "Jack and Jill" from nursery rhymes here. This beloved and familiar character from childhood nostalgia is reincarnated into a creepy doll in ginormous proportions who directs a deadly schoolyard game while shooting bullets out of crazy eyes. That's loaded.

NAYOUNG AIMEE KWON: South Korean directors do not always coddle global audiences and translate everything. There are many Easter eggs that audiences may not be privy to. The gigantic doll in the "Green Light Red Light" game, is actually a ubiquitous image of a girl character that appears in school textbook lessons. Her name is Younghi and her boy counterpart is Chulsoo, common names like "Jack and Jill" from nursery rhymes here. This beloved and familiar character from childhood nostalgia is reincarnated into a creepy doll in ginormous proportions who directs a deadly schoolyard game while shooting bullets out of crazy eyes. That's loaded.

Many Americans may not have caught the implications of the corrupt and privileged American characters who are masterminding and betting on the games as the have-nots are pitted against one another and forced to fight each other to the end. There is symbolism of the ongoing unequal dynamics between South Korea and the U.S. that goes back to when U.S. divided the Koreas in less than 30 minutes using a crude National Geographic map and installed its military in the South, in effect creating the division system of two polar oppositional regimes still at war half a century later.

Q: Some of the characters in Squid Games are not South Korean. What do their presence in the show underline about the social dynamics in South Korea?

KWON: Since the 1990s, South Korea has experienced tremendous population transformations. One factor was the Asian financial crisis and increased urban concentration of the population and resources, especially around the capital city of Seoul. These and other factors created a need in certain manufacturing and agricultural sectors and pulled in low-wage workers from areas like China, Southeast Asia and Africa.

North Korean refugees and ethnic Korean diaspora from China as well as from the former Soviet Union were also being pushed out by various political and socio-economic challenges in those regions that created additional push factors out of these areas into South Korea. Also, the increasing popularity of Korean popular culture and the successful tourism industry continue to draw people to Korea in recent decades into other sectors like the entertainment industry as well. “Squid Game” showed some of the diversifying aspects of contemporary South Korea including an actor from Pakistan who has become a local celebrity by playing migrant labor roles.

Q: What is happening in Korean art that is raising its international profile and why does inequality play such an important part?

KWON: Perhaps it is only natural for a society that has struggled with extreme inequalities throughout its long history going back thousands of years to have developed compelling storytelling practices in this direction. Before the modern era, there was a monarchical and aristocratic ruling order. There was strict immobility between the different social strata. Artists tended to come from either the higher literati or from the lower status groups. Some of the most iconic artists from the latter are kisaeng, or female entertainers, and p'ansori performers who often hailed from low-born groups like shamans and whose artistry embodied their struggles. They might interact illicitly with the upper classes and even influence their art, but these relations were not legitimated by society.

In the modern era, Korea was colonized by Japan, and then endured military occupation by the U.S., the division of the country that has lasted for over half a century with a still ongoing war between the North and South. With perceived and real external threats, internal inequalities are exacerbated. For example, gender inequalities that exist in most societies tend to get hyper-exaggerated in a militarized society like Korea. Most able-bodied college-age boys whose families can't afford to buy them out of service. are conscripted into the military during primecollege years. The underlying patriarchal inequality of this military culture of hierarchies seep into corporate culture, education and other arenas. In the 1980s, the rise of socially engaged Minjung Art, or people's art, became influential in various art practices including the New Wave of filmmakers. These new artists began to question more openly the unequal geopolitical condition of the Koreas under superpower influences especially the outsized impact of the U.S. that has always promoted itself as a savior until then.

When you have such a long history of artistic traditions of socially engaged artists standing up to and creatively engaged with social inequalities, you tend to get good at it. Again, I think this longer history is converging with new technological and distribution developments that are coming together in exciting new ways now.

Q: What accounts for the growing U.S. interest in Korean culture at this moment?

KWON: The world has been increasingly fascinated with Korean culture over the past couple of decades. It took a bit longer for this to manifest in full force in the U.S. I think this belatedness has something to do with the sheer strength and historic monolingualism of popular cultural industry mammoths like Hollywood that make it extremely difficult for new and especially non-English-language content to break in. Bong Joon-ho’s comment about the one-inch subtitle barrier in his Oscar speech was incisive.

Another interesting convergence is that there has been a tremendous demand for Korean culture and language courses in schools and universities. The Modern Language Association showed how Korean was one of the few languages that saw tremendous increases in enrollments in U.S. universities in the past decade.

Duke has been trying to raise its profile in Asian studies--currently has a campus in China, two M.A. programs in East Asian Studies, a Korean language program that has doubled in enrollments in the past 5-6 years. I hope we can turn to developing Duke's Korean studies program to meet these growing demands for a more well-rounded Asian studies program from our students and the community. UNC-Chapel Hill has been investing in this area in recent years. Building on the strength of what is already here, there is a tremendous opportunity to build these programs together in innovative new directions in the South.