When Duke Gave Shelter to An Egyptian Intellectual

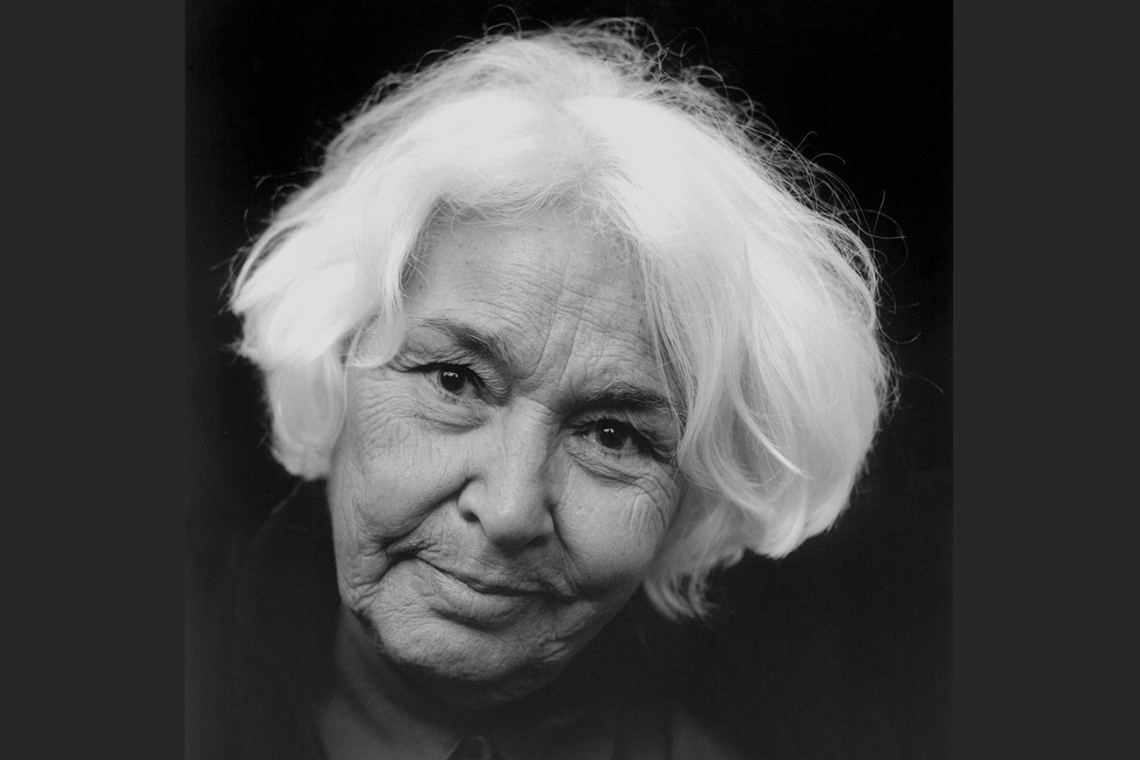

Nawal el-Saadawi, who died last month, spent four years at Duke escaping threats

When Egyptian writer Nawal el-Saadawi arrived at Duke University in January 1993, it was supposed to be a short-term residency. It ended up as a four-year visit that made for a series of memorable classes and lectures and lasting relationships between Saadawi and several Duke faculty and students.

Her time at Duke may also have saved her life.

Saadawi, who died March 21, was praised in obituaries in the New York Times and elsewhere as one of the leading feminist voices in the Arab world in more than 50 books of fiction and essays such as “The Hidden Face of Eve” and “A Daughter of Isis.” These works brought her global attention but also criticisms and death threats at home in Egypt. She came to Duke needing shelter both from Islamist groups who had targeted her for death and the Mubarak regime that alleged to be protecting her.

The visit was arranged with the assistance of Duke Professor miriam cooke, who had met Saadawi in the early 1980s, invited her to lecture at Duke several times and met her often in the Middle East. Cooke, the Braxton Craven Distinguished Professor Emerita of Arab Cultures, remembered this week the urgency of the arrangement with Duke.

“Two reasons to be concerned in late 1992,” cooke recalled in an interview this week. “A friend of hers, journalist Faraq Foda, had recently been murdered [by the Islamist group El Gama'a El Islamya after being accused of blasphemy by a committee of Islamic scholars]. Second, the same Islamists had put Nawal on a death list. They held a ‘trial’ they documented in a book called ‘Nawal el Saadawi in the Dock.’ It was a cheap and easily available book for anyone to read. And it concluded that because of all of her heretical statements, we condemn her to death.’

The Egyptian government assigned security officers to protect Saadawi and her husband Sherif Hetata, but Saadawi, who had been jailed in 1981 for her activism, felt no safer around them, cooke said. “She was more afraid of government guards sent to protect her than the Muslim Brothers. She said these were the same people who had guarded her in prison.”

In her autobiography, Saadawi put her situation in this way: “Would the fatal bullet be shot in my back by a bodyguard or in the front by those wearing a religious mask? As I sat in my home surrounded by enemies on every side, not knowing what to do, fortune intervened.”

At the time, there was no Scholars at Risk, no formal programs for universities around the world to offer protection to scholars under threat. Fortune instead came from a Duke alumna, Elizabeth Oram, a former student of cooke’s, who -- after speaking to Saadawi -- expressed to cooke the urgent need for assistance.

There was no available money in her program, but cooke went to then Trinity College Dean Malcolm Gills and explained the situation.

“We didn’t know whether she needed two weeks, two months or what. We didn’t know how long the danger would last. But Malcolm said, ‘Bring her here, just find a way to bring her. We’ll find a way to support Sherif and her.’”

In many ways, the ad hoc effort recalled the remarkable university initiative to provide safe harbor to European scholars in the years just before and during World War II. The university-wide emergency effort brought several notable Jewish scientists and physician researchers to Duke as well as Raphael Lemkin, the legal scholar who is credited with later coining the term genocide.

Saadawi’s short visit become one year and then went into a second and third and finally part of a fourth before she felt it was safe to return to Egypt. During that time she and Sherif taught numerous classes at Duke and gave talks here and throughout the region. She also wrote the first two volumes of her autobiography – a planned third was unfinished at the time of her death.

At Duke she connected not just with faculty in other departments, such as Walter Mignolo of the Department of Literature, who said he saw Saadawi as a kindred “Third World Intellectual.” She also influenced many of her students, who found her ideas inspiring and her classroom approach unusual in American education.

At the memorial, Professor Emeritus Bruce Lawrence read a message from an alumna who had taken a first-year seminar with Saadawi that robustly challenged the new students. In the end, the student said, the class had been among the most valuable she took because “we realized, even then, that never for a moment was Nawal going to let us be just a class of 18 year-old freshmen.”

Lawrence also quoted a former graduate student who took a 1993 class on women in Arab politics with Nawal and Sherif. The student said he expected the two to be “stern, imposing figures of undeniable authority.”Instead, the entire large class seemed surprised when the first three sessions consisted of the students sharing their ideas on several topics while Nawal and Sherif remained mostly quiet. Only in the fourth class did they start discussing their own experiences.

The student said that near the end of a memorable semester, he asked Sherif why they had remained so quiet.

He answered: “If you've been in prison for 13 years, three days of awkwardness is not too long to wait to get a class of students to open up.”

That was characteristic of Saadawi, cooke said. She had a “charismatic fierceness,” combined with creativity and the courage to confront injustice, often with a bright smile, sly barbs and critical humor. After Saadawi returned to Egypt still on a death list, she continued to forcibly speak out, lecturing religious leaders on points of the Quran on national television and unveiling the communist background of one in a public dining room.

When they heard of her death, cooke and Lawrence read YaSin, the Qur’anic chapter recited for the dead. “As we read, we felt she was with us. I suspect, however, she was scolding us for what she would have called was our superstitious reaction to her departure. But I like to think that perhaps also she was smiling her 100-watt smile."