Working Toward Racial Justice

Tracing stories of Duke's first Black workers

In a 1992 article about the transition of Durham County from a textile and tobacco town to high-tech community, William V. Bell, then chair of the Durham County Board of Commissioners, described Duke in a way others had privately expressed.

“It’s no secret that in some circles, Duke is still thought of as a plantation …” Bell said in the article, which appeared in a special insert of Duke Dialogue, the university newspaper. “To Duke’s credit, it hasn’t ignored these issues. It has attempted to address them.”

The reference to Duke as a plantation reflects a complicated history that Duke continues to wrestle with today.

Some of that history was explored during the university-wide “Living While Black” symposium last summer when more than 50 Black faculty, staff and students shared stories of discrimination, presented research on racial inequities and issued urgent calls for change.

“Black hands have always been at work at Duke, even before Duke was Duke,” Chandra Guinn, former director for the Mary Lou Williams Center for Black Culture, told the 6,300 members of the Duke community who attended the online symposium.

Tracing the stories of the first Black workers at Duke is difficult because their biographies are poorly documented. However, their histories will be a focus of new academic research funded by the Duke Endowment in 2021.

“Understanding and knowing history helps us think critically and strategically about what work there is left to do,” she said. “We have to understand where we’ve been in order to capitalize on the lessons learned. It is demoralizing not to admit to progress, but

it is utopian to think that everything is alright.”

‘Before Duke was Duke’

While Duke University was established in 1924 – after the Civil War and emancipation of enslaved people – the university traces its origins back to 1838 when Brown’s Schoolhouse was established in Randolph County.

Finding information about Duke’s first Black workers has often led to dead ends.

“There is a lot we don’t know yet,” said University Archivist Valerie Gillispie. “There is more work to be done to investigate enslaved people and workers after the Civil War and really try to understand their biographies and their stories.”

One of the better known stories is of George Wall, a formerly enslaved person hired at the age of 14 in 1870 to work on the Trinity College campus in Randolph County. Wall, who was among Duke’s first documented Black employees, moved with the school to Durham in 1892 and worked as a janitor until his death in 1930, marking 60 years with Trinity College and Duke University. He purchased land near East Campus and helped establish a neighborhood later named Walltown after him.

George-Frank Wall, one of Wall’s nine children, worked for Trinity College and then Duke University until his death in 1953. In his will, George-Frank Wall, dubbed the “sheriff of the dining halls,” left all of his possessions to his wife – except for $100, which he gave to Duke University.

“I want to impress on other colored men, the fine and good relations between Christian White People and Christian Negroes,” wrote George-Frank Wall in his will, according to an article in the September/October 2012 issue of Duke Magazine. “For seventy-five years, I have been employed by said institution and never a cross word but Christian Harmony.”

As more Black workers filled the ranks at Duke, a struggle for racial equity and civil rights emerged.

Fight for Civil Rights

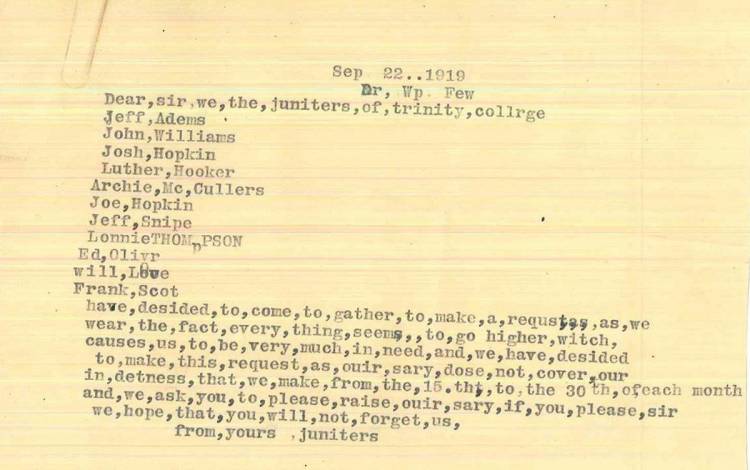

While documentation of Black workers in Duke’s early years is scant, there is a letter from 11 Black janitors to President William Preston Few dated Sept. 22, 1919, that highlighted concerns about pay.

The letter pleaded for a wage increase, concluding, “We hope that you will not forget us.”

Wage disparities among Black workers at Duke continued in the 1960s. While federal minimum hourly pay was $1.25 in 1965, Black workers earned less because universities and other non-profits were exempt from federal minimum-wage regulations. According to a 1965 article in The Chronicle, maids earned 85 cents per hour; janitors made between 95 cents to $1.05 per hour.

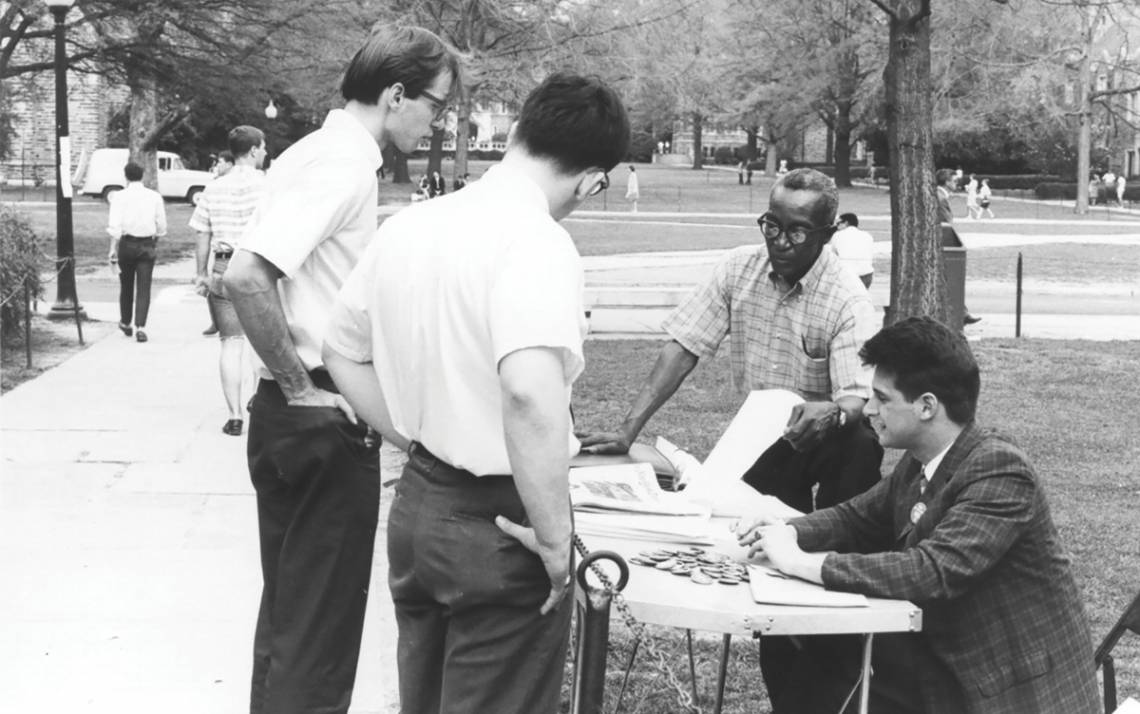

Oliver Harvey, a janitor and later supervisor, organized a campus effort to bring about change.

In February 1965, Harvey established the “Duke Employees Benevolent Society” to campaign for higher pay and enhanced benefits and working conditions. By September, he transformed the group into Duke’s first labor union, the Local 77 chapter of the American Federation of State, County & Municipal Employees. Two months later, the university agreed to improve pay and benefits. Local 77 remains Duke’s largest union on campus today.

Living While Black Today

In recent years, racially charged incidents have continued to occur at Duke and other college campuses across the country. Such events have led to initiatives at Duke to address systemic racism. Duke also created a website Anti-Racism at Duke, a central repository for data and training and to learn about new and ongoing programs.

Valerie Ashby, the first Black dean of Trinity College of Arts & Sciences, said Duke’s willingness to confront racism attracted her to the role of dean and why she participated in the Living While Black symposium.

“I chose to come to Duke, not because Duke was perfect, but because Duke seemed to me to be a place that wanted to do the work,” Ashby said during the symposium last summer. “I’m hopeful that when we do the work, we are a place that can be different. Wouldn’t it be a great day if people stopped calling us ‘The Plantation’? How beautiful would that be?”

Please share your story idea for this series with us here.