How Contact Tracing Keeps Duke's COVID Response Nimble and Effective

In the weeks following the return of Duke students to campus this fall, a comprehensive plan that involved robust testing, reduced the campus residential population and reconfigured classrooms and public spaces for physical distancing kept positive numbers low and the campus safe.

But even in the first weeks, a troubling trend caught the attention of campus officials: Many of the positive cases came during meals, when students were lowering their guard. This presented a potential weak point that could allow the COVID virus to spread despite Duke’s efforts.

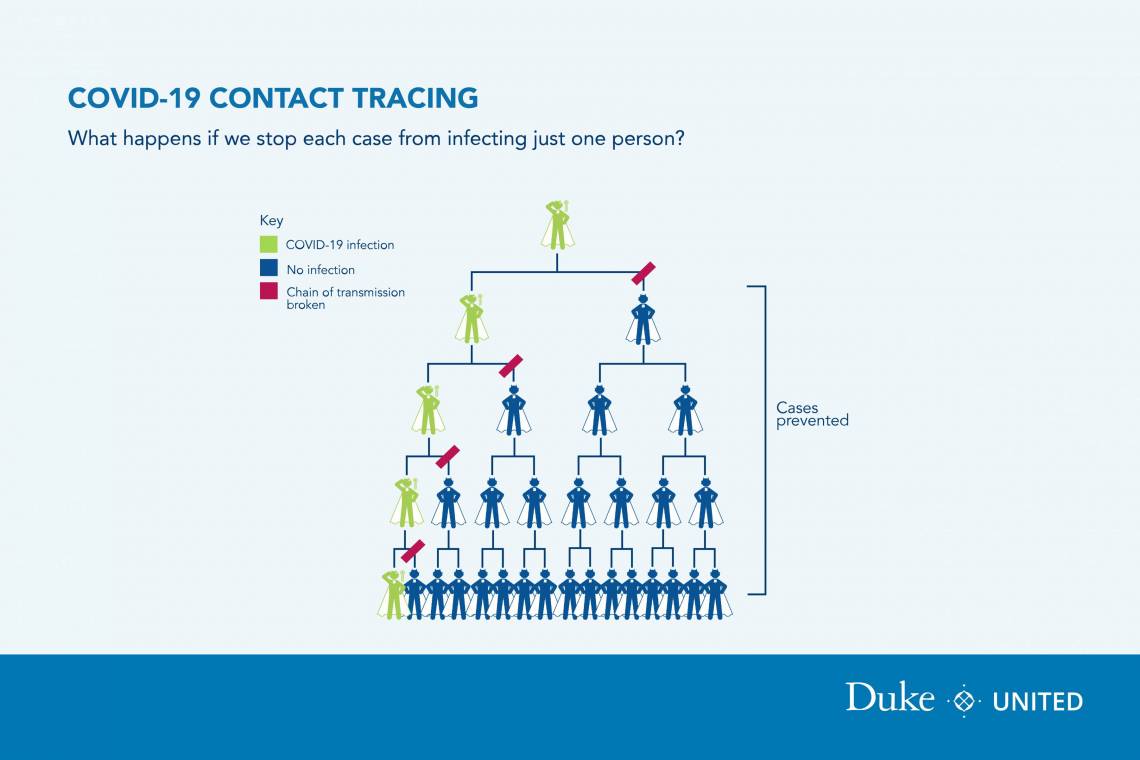

Duke officials knew all this through one of the lesser known parts of the campus plan: comprehensive contact tracing of people who tested positive. In the months since campus reopening, contact tracing has played a quiet but valuable role in keeping Duke’s numbers low following the first weeks.

The program is getting exposed Duke students into quarantine quickly, limiting any cascading effects of positive exposure, and getting isolated and quarantined students back into normal life quicker than otherwise possible.

One telling sign of the success of the program in limiting exposures: Of the 57 students who tested positive between Aug. 2 and Sept. 28, 15 people -- 26 percent -- were identified by COVID testing following contact tracing. These students are often asymptomatic, which means the contact tracing got these students into isolation several days before any red flags would have appeared.

Laura Andrews, associate dean of students who is coordinating the contact tracing for students, said the program allows Duke to nimbly act to stop potential outbreaks, as in the case of exposure during meals.

“What we learned early on is that people weren’t putting their masks back up after eating,” Andrews said. “And they weren’t staying more than six feet away from others. We saw these exposures, and very quickly we asked to get a campaign through social media and other channels to raise student awareness of this problem.”

“One telling sign of the success of the program in limiting exposures: Of the 57 students who tested positive between Aug. 2 and Sept. 28, 15 people -- 26 percent -- were identified by COVID testing following contact tracing. These students are often asymptomatic, which means the contact tracing got these students into isolation several days before any red flags would have appeared.”

While the evidence from the contact tracing spurred a student social media campaign aimed at safe mealtime behavior, other groups also identified the issue and got involved in the campaign. The C-Team, a group of student volunteers and redeployed staff members who walk the campus encouraging students to comply with COVID instructions and thanking them for doing so, spread the message about safe eating habits. Meanwhile, facilities teams cabled down tables and chairs to prevent them from being moved, and posted signs everywhere reminding students to follow best practices during and after eating.

Officials soon saw a significant decline in exposures during eating, a result that continues months later, Andrews said.

The contact tracing team itself is made up of “redeployed Duke employees and volunteers doing six to 12-hour shifts,” Andrews said. “Some of the volunteers are Duke retirees who want to contribute to campus safety.”

The team’s work begins when Student Health identifies a student who tested positive and passes that name on to the contact tracing team member running that shift. The contract tracing team then has a two-fold goal: to find out how the student got exposed and who they may have exposed.

Even before the team interviews the student, a lead tracer has collected basic information from various units, such as class schedule and residences, sometimes even a record of Duke Card swipes, all of which influences the questions asked to the student.

The interview is both informal and confidential, Andrews said. “Much of the interview isn’t even about collecting information, but building rapport and making sure the student knows that they are not in trouble. We need them to trust that we’ll be responsible with their information so they give us a full accounting of their activities.”

Speed does count here. All positive students are contacted by the contact tracing team within an hour of the team being notified.

Using Centers for Disease Control guidelines defining close exposures, the contact tracing team then turns to finding the students who were exposed. (If an employee is named, that information is turned over to Employee Health and Occupational Wellness, who oversees contact tracing for employees. If the student has gone into the community during the time, that information is shared with Durham Public Health.)

The student who tested positive goes into isolation, while the exposed students receive COVID tests before heading to quarantine. “Because the process is confidential, we never tell the exposed students who it was that exposed them,” Andrews said. “But they often have already been told by the student.”

For Andrews, one takeaway from the experience is that Duke’s success to date on COVID has a lot to do with having a multifaceted plan, involving students, faculty and staff from numerous units, with each having a part to play and those parts fitting neatly together.

Andrews said she is proud of the role her contact tracing team has been able to play.

“Contact tracing is a partnership between a lot of different places,” she said. “We work closest with Student Health, but we are connecting with units across the campus. That teamwork allows us to pick up positives so quickly. And that’s helping our entire plan work well.”