Years ago, Theater Studies Professor Neal Bell was asked to do a complete screenplay overhaul of a horror movie being shot in Toronto. The director, who shared a similar theater background, remembered that Bell was a horror buff, so he flew him to Canada to see the finished movie sets (mainly those of a shady hospital). Then, the producers informed him that he had a mere two weeks to write a completed screenplay.

Years ago, Theater Studies Professor Neal Bell was asked to do a complete screenplay overhaul of a horror movie being shot in Toronto. The director, who shared a similar theater background, remembered that Bell was a horror buff, so he flew him to Canada to see the finished movie sets (mainly those of a shady hospital). Then, the producers informed him that he had a mere two weeks to write a completed screenplay.

While Bell always loved movies, he’d never written a screenplay—so he pulled a 14-day version of an all-nighter and finished a draft. It was that crash course which launched his study of movie writing. Over the years, he’s watched countless movies and read some of the greatest screenplays, including one of his personal favorites: Robert Towne’s “Chinatown.”

His latest book “How to Write a Horror Movie” (Routledge 2020) brings together his affinity for horror movies and his success as a playwright—and is quite appropriate for the Halloween season.

Q: How did this book materialize?

BELL: I’d been asked to do a peer review of a book for Routledge, and one of the questions asked was whether or not I had any book ideas knocking about. I’d been teaching a course on horror for several years at Duke and thought a book about how to write a horror movie might be fun—and in fact, it turned out to be so. It was also a major change of pace for me. I’m primarily a playwright and had never written anything like a “How To” book before.

Q: What are some of the biggest misconceptions about writing for the horror genre?

BELL: One of the most basic mistakes is to show too much of the monstrous. Our imaginations run wild as long as the “fearful thing” remains unseen, but there’s often a sense of letdown once whatever is hiding in the closet or under the bed is finally revealed.

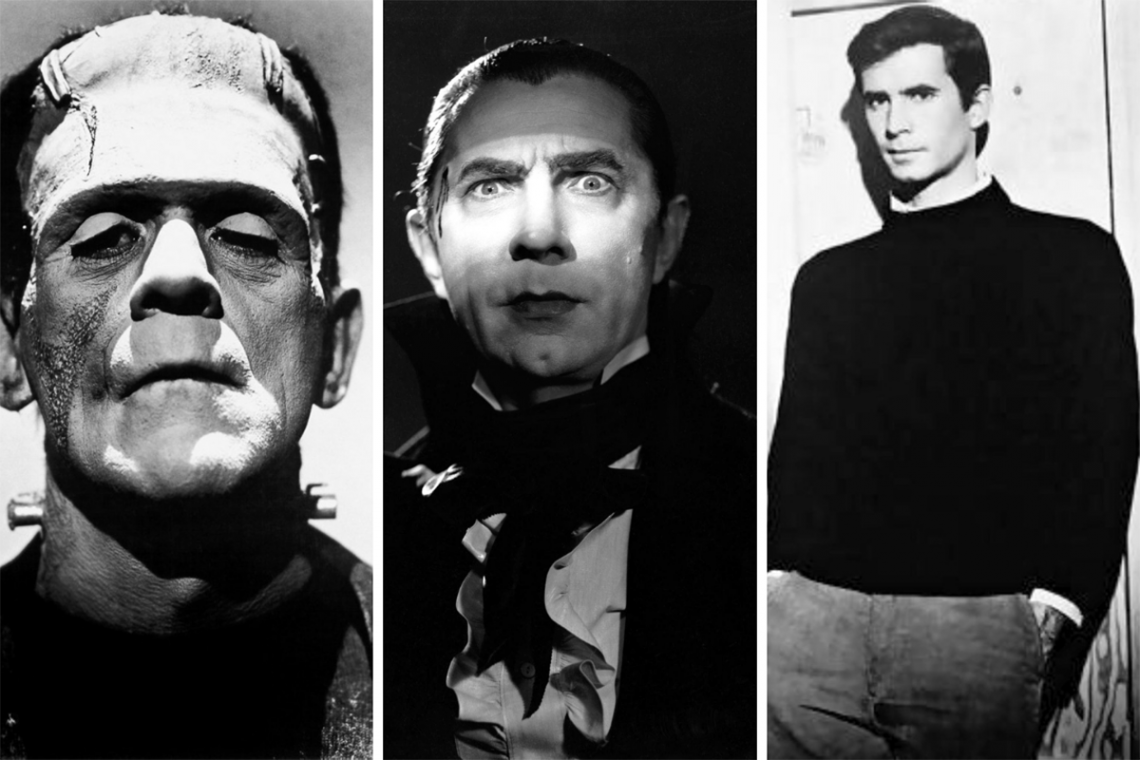

A great director like Alfred Hitchcock knows this. That’s why he never showed the audience Norman Bates’ murderous mom up close until the very end of “Psycho.” A very different filmmaker, Ridley Scott, uses a similar strategy in the slow reveal of the title creature in “Alien.” We only get subliminal glimpses of Xenomorph until very late in the day. When we finally see the full-grown alien—a giant with two sets of devouring jaws—the shock is not at the creature per se, fearsome though it is, but at the vast and endlessly unknowable universe in which Man is not even close to being the alpha predator.

Q: In the book’s introduction, you state the horror genre is “always popular but often disrespected.” Why do you think that is?

BELL: All cultures produce fearful stories. “Gilgamesh,” the oldest recorded epic, looks without flinching at one of the things we’re still, and perhaps will always will be, afraid of: the finality of death. Film critic Robin Wood once suggested a formula for the horror film: Normality is threatened by the monster.

The best horror movies ask us to question both parts of that formulation— what we think of as normal and how we define the monstrous. And these movies ask their questions in ways both thought-provoking and visceral. It’s the visceral part–our lizard brain reacting to a threat–that gives horror movies their “disrespectful” aspect. They shake us up because they’re intended to, but it’s often too easy to shake us up with a cheap jump scare or buckets of blood.

The horror master Stephen King divides the genre up three ways, calling terror (fear of the unknown) the finest emotion to evoke, horror (involving tangible threats to body and life) coming in second, and revulsion at the bottom. Too many horror movies settle for the gross-out, e.g. “The Human Centipede.”

Q: What is an example of a screenplay that you think successfully translated into a horror movie?

BELL: One of the best horror movies in the last five years is Jordan Peele’s “Get Out.” It received stellar reviews, won an Oscar for best screenplay, and cleaned up at the box office. And yet the script made the rounds of studios for years before Blumhouse Productions finally took a chance on it.

The script is a fearless confrontation with brutal systemic racism that begins as social satire. A young Black man accompanies his white girlfriend to her wealthy family home and has to fend off endless microaggressions by the white “liberals” who embrace him, while feeling more and more like something isn’t quite right with this setup. In the script’s final third, there’s a jolting pivot–from satire to outright horror—but the clues to that horror have been very carefully planted throughout the script’s first two acts.

And when the audience gets the big reveal, they realize the film is doing much more than scaring them. It’s saying, “This is what racism looks like.” And it’s devastating.

Q: How did your interest in horror movies develop?

BELL: I’ve always loved—and been afraid of—being scared, similar to the love-hate relationship some people have with roller coasters. My older brother blames a children’s book we were subjected to as kids, a weird German book of moral poems with suitably grotesque illustrations called “Slovenly Peter”–in which kids with bad habits were brutally punished. For example, the kid who sucks his thumbs gets them cut off, a girl who eats too much sugar melts in the rain, and so on. It’s a horrible book, and was a best-seller way back then. As much as it scared me, I’ve never forgotten it.

Movies were trickier to access because my parents controlled the television and wouldn’t let me see any films they thought were inappropriate. But I clearly remember one time when my pestering paid off, and my father took me to the sci-fi/horror movie that I was dying to see: “The Angry Red Planet.” It had, the television ad promised, giant killer amoebas—among other terrors. How could it not be great?

So, I settled into my seat, watched the first 30 minutes or so with my dad, and then, completely freaking out (because those amoebas were terrifying), said with an effort to be nonchalant, “Okay, I’ve seen enough. We can go now.” My Dad responded, “You dragged me here, now you’re watching the whole thing.” Lesson learned: If you’re going to a scary movie, plan an exit strategy.

Bell’s book “How to Write a Horror Movie” is available through Routledge. To order, please visit the Routledge website.