Duke’s New Dean of Students: How Prince Saved My Life

John Blackshear didn’t always have it easy growing up. He had a loving mother, but there was also violence in the home. And outside, bullies called him sissy and gap-toothed.

“I went through it,” Blackshear said. “I needed a place of refuge to stay sane at a really insane time; music is where I found it, and nobody did it for me like Prince.”

That refuge helped keep Blackshear on a path that eventually led him to Duke, where he has served students in various capacities for two decades. On August 1, he became dean of students and associate vice president of student affairs.

“I'm just delighted that I get to serve students in this interesting new way,” Blackshear said.

Prince, the fiercely independent multi-instrumentalist also known as His Purple Majesty, died in 2016. A preternaturally talented musician, Prince was also confrontational, sexually ambiguous, and defiantly whoever he wanted to be in any given moment. That commitment to authenticity has resonated with Blackshear throughout his own life and career as a psychologist and teacher.

Prince, the fiercely independent multi-instrumentalist also known as His Purple Majesty, died in 2016. A preternaturally talented musician, Prince was also confrontational, sexually ambiguous, and defiantly whoever he wanted to be in any given moment. That commitment to authenticity has resonated with Blackshear throughout his own life and career as a psychologist and teacher.

“I love his freedom, I love that he knew he wasn't normal, and that he embraced his unique qualities and really put it right in front of us,” Blackshear said. “The way he looks at you on his album covers, it’s almost like he’s challenging you to question what you see.”

Blackshear grew up in Savannah, Ga. He was drawn to music early, not least because he associated it with peace, tranquility and calm.

“When we had music playing and food cooking,” he said, “it seemed like everybody was OK.”

Sometime around 1979, when he was about 7 years old, Blackshear heard the Prince ballad “Still Waiting” blaring from a neighbor’s yard.

“I don't know what made me pause and listen to the lyrics,” he said. “I thought it was a woman singing, and there was this longing in the voice. And I asked one of the older kids, who said ‘It's Prince.’ And so in my mind I was thinking, a girl named Prince, that's interesting.”

Blackshear saw the album with a topless (and clearly male) Prince on the cover at K-Mart and begged his mother to buy it until she caved. He came home and played it on his plastic Fisher-Price record player, reading the liner notes and marveling at how Prince had written, performed and produced the album entirely by himself.

“I remember thinking, this one person did all of this,” Blackshear said.

The connection he felt deepened when he read Prince also had grown up around domestic violence and parental breakup.

“He felt lost and alone in the world, and channeled all of that into being this excellent musician,” Blackshear said. “I felt like he was a testimony to those of us who felt the same way, that if you immerse yourself in this particular way, that you can make it right.”

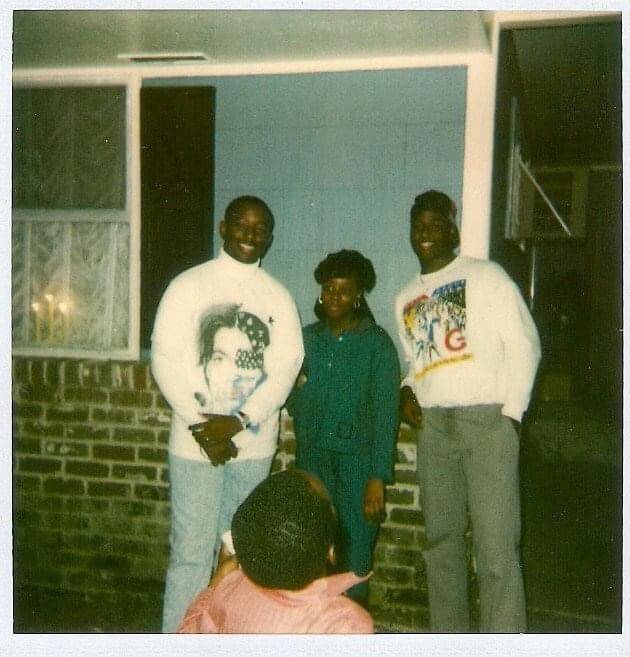

Will Holmes – who preferred Michael Jackson – has been friends with Blackshear since third grade. In Blackshear’s room, where a Prince poster covered the whole door, they would argue over whether Prince or Jackson was better, “loud enough for his mom to yell at us to calm it down,” Holmes said.

Prince also became Blackshear’s refuge when he was teased or bullied – which was often.

“Listening to Prince was the way I would reorient myself back to feeling OK,” he said. “This guy who I know had been bullied like nobody's business, he took everything that made him different, and did not let it diminish him. Every single thing people thought about him that was supposed to be problematic, he amplified it and made it great.”

That, Blackshear said, is why he feels Prince saved his life.

“I get to amplify my own traumatic history as a testimony for other folks who are dealing with trauma; that you can survive that, you can be happy and you can give the world something that speaks to the next person behind you,” he said.

Prince also inspired Blackshear to get serious about music. Lyn Wise, Blackshear’s aunt, said he was the first drummer their church ever had, before he was even in middle school.

Blackshear credits her with fanning his musical spark. Wise took him to his first concert: Michael Jackson on his “Off the Wall” tour at the Savannah Civic Center. Years later, he returned the favor by bringing her to a Prince concert in Greenville, S.C. That was one of the 23 times Blackshear watched Prince perform live.

“When Prince died, the first person I thought of was John,” Wise said. “Everyone who knew he loved Prince called him. You’d have thought Prince was one of his relatives.”

Growing up, Blackshear’s drumming brought him into contact with kids from different backgrounds, kids he wouldn’t otherwise have met, keeping him out of trouble.

“We all came together to form bands, we all loved Prince, that was the thing that we all had,” he said. “I spent so much time immersed in it, it kept me focused on things that worked out to my benefit.”

His skills on the drum kit landed Blackshear a scholarship to Florida A&M University, where he realized he couldn’t drum well enough to be in Prince’s band. But it’s also where he discovered and fell in love with psychology. He took the lessons he learned from Prince and the other masters of their musical craft he loved – Joni Mitchell, Stevie Wonder, Miles Davis – into that domain.

“What they did was the ultimate expression of who they are,” he said. “You don't have to be on the stage and playing the drums. You're an artist when you go and you do your work.”

Blackshear eventually became a clinical psychologist, and in 2001 he came to work at Duke’s Counseling and Psychological Services. His work supporting Duke students has ranged from being student ombudsperson and supervising low-income and first-generation scholarship and success programs, to being dean of academic affairs for Trinity College of Arts & Sciences.

He also teaches forensic psychology as an adjunct instructor in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, and it should not be surprising to learn he takes lessons from Prince’s music into the classroom, channeling that confidence that he can bring everyone along for the ride.

“It’s a commitment to being genuine,” he said, “while staring out at the world saying, ‘you’re gonna love this. Trust me.’”

Now, Blackshear is almost certainly the first dean of students at Duke with a tattoo of the Prince symbol on his arm. He also steps into the role at the start of an unprecedented year, as the university grapples with the ongoing pandemic.

“We're asking students to take on responsibilities that adults don't seem to be doing very well,” he said. “To raise consciousness about behaving in a way that takes care of not just themselves but their fellow students, and that's a cultural shift for sure.”

But just as in the classroom, Blackshear’s overarching goal remains challenging students to find and embrace their authentic selves.

“Be the you that you are, and there should only be one of you, only one,” he said. “Most of the time you suffer when you are forced to live inauthentically as opposed to embracing that you're perfectly who you are, who you were designed to be. And Prince gave me that.”