Poems for this moment

April is National Poetry Month. As the coronavirus pandemic continues, we wondered if Duke’s writers and literature scholars are turning to particular poems right now, perhaps for their beauty, wisdom, or potential to inspire, or as a mirror for this moment. Duke Today reached out to three professors in Duke’s English department and literature program with the question, “What poem are you reading now?”

Faulkner Fox, a writer and lecturing fellow in the English department, is the guiding force behind the “Poem of the Day” project at the Sanford School’s Hart Leadership Program.

Faulkner Fox, a writer and lecturing fellow in the English department, is the guiding force behind the “Poem of the Day” project at the Sanford School’s Hart Leadership Program.

With this project, the Hart program is posting a new poem on its website each day. The project has very personal origins, as Fox explains:

“On March 14th, I talked to my father on the phone. He had fallen and was feeling very weak. He's 80 years old, with Parkinson's.

We talked about what he might do while he was too weak to do much. I suggested reading poems if he couldn't read anything longer. He asked me to send him some.

By the time I emailed him a poem the next morning, he was in the ICU with what, eventually we understood, was COVID-19. He was one of the first confirmed COVID-19 patients in the state of Virginia.

He is out of the ICU now and recovering—even though we were told he had a less than 10 percent chance to survive.

I realized there's never a reason to wait to send poems. So I started sending them to lots of people, including my students.

A week later, the Hart Leadership Program decided to collect the poems I was emailing, calling it “Poem of the Day.”

Here is the poem I emailed to my father then faxed to the ICU. It’s also the first poem I sent out to lots of people in my life.”

blessing the boats

(at St. Mary's)

may the tide

that is entering even now

the lip of our understanding

carry you out

beyond the face of fear

may you kiss

the wind then turn from it

certain that it will

love your back may you

open your eyes to water

water waving forever

and may you in your innocence

sail through this to that

Ariel Dorfman, professor emeritus of literature, has found himself returning recently to a very old Spanish poem by Francisco de Quevedo:

Ariel Dorfman, professor emeritus of literature, has found himself returning recently to a very old Spanish poem by Francisco de Quevedo:

“Some years ago, I was among 100 men to be asked by Amnesty International to select a poem that made me cry (that book was followed by one that had 100 women offer their own preferences). The sonnet that I chose was written by Francisco de Quevedo back in the 17th Century and seemed to be a way of expressing the love I felt, beyond death, for my wife Angélica.

I have returned often to these verses, and more so today when a plague rages and an early death carries away far too many of our fellow humans on this planet. The fact that, along with the fine translation into English, I include the Spanish, allows us to feel compassion towards the multitudes of our foreign brothers and sisters who are suffering this pandemic in a language we may not understand but who share with us the need for the solace of a poem that declares that death may come for us but it cannot stop us from being ashes in love.”

Love constant beyond death

By Francisco de Quevedo (1580-1645) Translated by Margaret Jull Costa

Though my eyes be closed by the final

Shadow that sweeps me off on the blank white day

And thus my soul be rendered up

By fawning time to hastening death;

Yet memory will not abandon love

On the shore where first it burned:

My flame can swim through coldest water

And will not bend to laws severe.

Soul that was prison to a god,

Veins that fueled such fire,

Marrow that gloriously burned -

The body they will leave, though not its cares;

Ash they will be, but filled with meaning;

Dust they will be, but dust in love.

Amor constante más allá de la muerte

Cerrar podrá mis ojos la postrera

Sombra que levare el blanco día,

Y podrá desatar esta alma mía

Hora a su afán ansioso lisonjera;

Mas no, de esotra parte, en la ribera,

Dejará la memoria, en donde ardía:

Nada saber mi llama el agua fría,

Y perder el respeto a ley severa.

Alma a quien todo un dios prisión ha sido,

Venas que humor a tanto fuego han dado,

Médulas que han gloriosamente ardido:

Su cuerpo dejará, no su cuidado;

Serán ceniza, mas tendrá sentido;

Polvo serán, mas polvo enamorado.

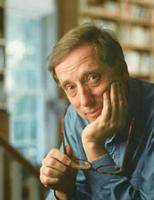

Thomas Pfau, professor of English and German, is teaching a course in poetry to Duke undergraduates this spring. For Pfau, the poetry of Nobel Prize-winning writer Czeslaw Milosz (1911-2004) resonates right now:

Thomas Pfau, professor of English and German, is teaching a course in poetry to Duke undergraduates this spring. For Pfau, the poetry of Nobel Prize-winning writer Czeslaw Milosz (1911-2004) resonates right now:

“Czeslaw Milosz is someone whose work I hold in exceptionally high regard. His often harrowing experience of 20th-century European history give his voice a gravity quite apposite to our present moment.”

A Song on the End of the World

By Czeslaw Milosz

Translated by Anthony Milosz

On the day the world ends

A bee circles a clover,

A fisherman mends a glimmering net.

Happy porpoises jump in the sea,

By the rainspout young sparrows are playing

And the snake is gold-skinned as it should always be.

On the day the world ends

Women walk through the fields under their umbrellas,

A drunkard grows sleepy at the edge of a lawn,

Vegetable peddlers shout in the street

And a yellow-sailed boat comes nearer the island,

The voice of a violin lasts in the air

And leads into a starry night.

And those who expected lightning and thunder

Are disappointed.

And those who expected signs and archangels’ trumps

Do not believe it is happening now.

As long as the sun and the moon are above,

As long as the bumblebee visits a rose,

As long as rosy infants are born

No one believes it is happening now.

Only a white-haired old man, who would be a prophet

Yet is not a prophet, for he’s much too busy,

Repeats while he binds his tomatoes:

There will be no other end of the world,

There will be no other end of the world.

Warsaw, 1944

Late Ripeness

By Czeslaw Milosz

Translated by Robert Hass and Czeslaw Milosz

Not soon, as late as the approach of my ninetieth year,

I felt a door opening in me and I entered

the clarity of early morning.

One after another my former lives were departing,

like ships, together with their sorrow.

And the countries, cities, gardens, the bays of seas

assigned to my brush came closer,

ready now to be described better than they were before.

I was not separated from people,

grief and pity joined us.

We forget—I kept saying—that we are all children of the King.

For where we come from there is no division

into Yes and No, into is, was, and will be.

We were miserable, we used no more than a hundredth part

of the gift we received for our long journey.

Moments from yesterday and from centuries ago—

a sword blow, the painting of eyelashes before a mirror

of polished metal, a lethal musket shot, a caravel

staving its hull against a reef—they dwell in us,

waiting for a fulfillment.

I knew, always, that I would be a worker in the vineyard,

as are all men and women living at the same time,

whether they are aware of it or not.

Tsitsi Jaji, a poet and professor of English, has included guest appearances by poets in her remote classes this spring.

“I have had guest poets from Botswana/UK, Nigeria/US, and Carrboro’s poet laureate join my classes in the last couple weeks, so I’ve been reading their poems with my class – not as comfort so much as that part of the “everyday” that is actually almost always extraordinary if we pay attention.

Poetry so often teaches me to feel for the human in the inner world of an unknown.

Here’s one of my favorites, from T.J. Dema’s book "The Careless Seamstress”:

A Benediction for Climbing Boys

By Tjawangwa Dema

1.

Sometimes the chimney was hot or alight.

They sent us up anyway, mostly naked.

At night we, sleeping black,

dreamt of the bakers on Lothbury,

of tight flues and endless winding.

The first time Jonny went up,

there was not even four years behind him.

He was up while the chimney was cold,

before the morning fire was lit. His skinny limbs,

cramped, waited for the mason’s cutting tools.

Luck for the bride who sees us perhaps.

But we are black and blind with falling soot.

We are burnt and scraped, our knees

set to fire with brine and brush

to harden our small hearts.

In the fairy tales, the sweep finds love

with a porcelain shepherdess.

After May day, we are turned from the table

to which we return, for the world gifts us

only sack cloth and ashes.

2.

there is no cap coarse enough

to keep the soot from eye or mouth

No talisman of brass cap badges

to shame the master who sends them up

to fall from roofs and chimneys

to lodge in flues and suffocate

Whose son has fire set under him

his heels pricked to mend his pace

This is the cold fate of he who is alone

whose mother has died, left his body

for the world to take and make coal

and whose back is bent in youth

his scrotum set to eat itself away

we die knowing what is denied us

air and love, a clean wanting

we fall, we hope, to something warm

that union that sought us out

first as fire now as ash

has left us invisible, sooty faced

only grace lets us fall