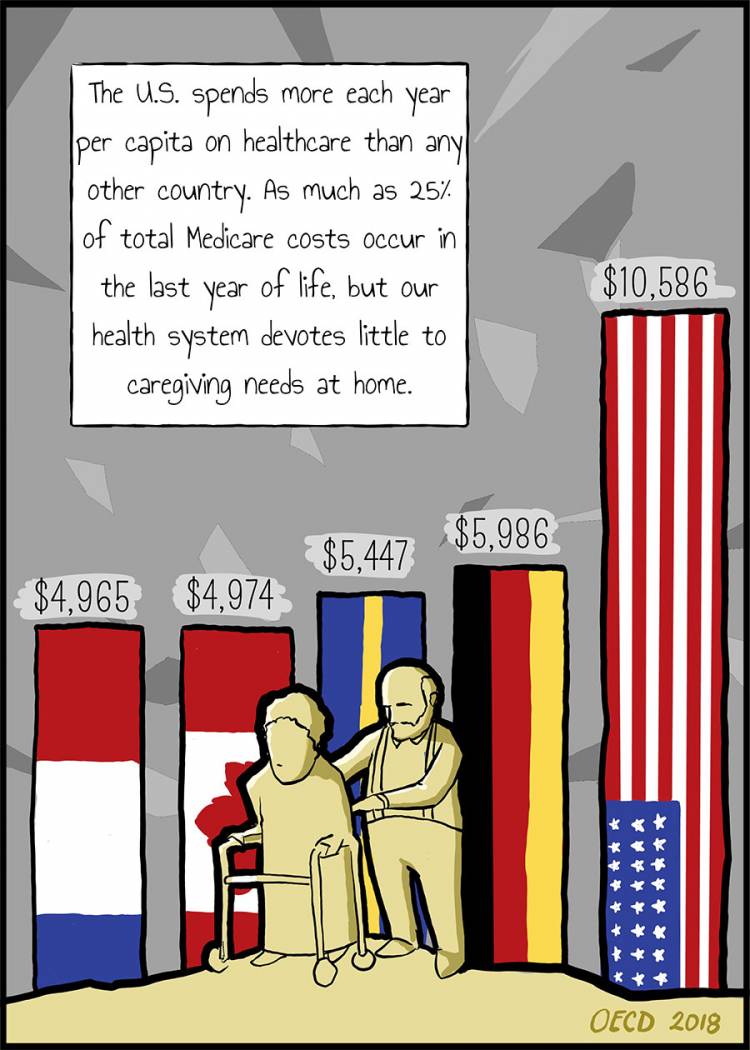

Dr. Nathan Gray is an assistant professor of medicine and palliative care at Duke University School of Medicine. As part of his work, he explores health care issues through graphic opinion pieces. Previously, he collaborated with another Duke doctor on how cancer care can bankrupt families.

This article previously appeared in the Los Angeles Times.