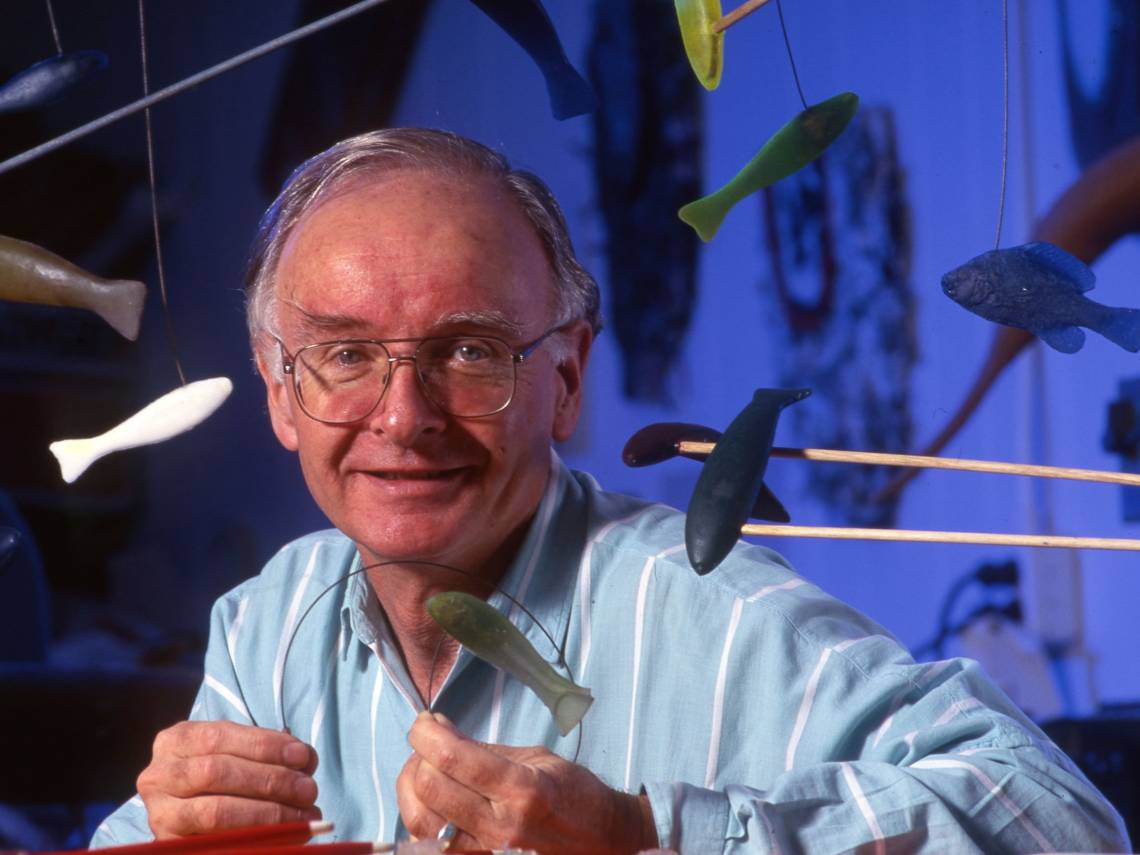

Duke Flags Lowered: Scientist-Sculptor Stephen Wainwright Dies

Over more than 30 years at Duke, the discipline-straddling professor helped shape the field of biomechanics

DURHAM, N.C. -- Stephen A. Wainwright, a Duke University zoology professor whose work merged marine biology, engineering and art, died on December 12 at his home in Chapel Hill. He was 88.

When Wainwright looked at a tuna, or a mackerel, he didn't just see a fish. He saw a living machine, whose parts -- from its stiff-but-flexible backbone and undulating body, to its propeller-like tail -- were exquisitely designed for swimming.

He regarded all living things with the eye of an engineer: the shape and makeup of a clam shell, the stiffness of a starfish. To Wainwright, animals ranging from sharks and eels to sea cucumbers were all essentially bendy cylinders, encased in a fabric-like wrapper of connective tissue that allowed their bodies to be supple or stiff.

Wainwright was the co-founder, along with Duke zoology professor Steven Vogel, of the field of comparative biomechanics, which uses principles of engineering and physics to study how animals move and function.

Wainwright was born on Oct. 9, 1931, in Indianapolis, Indiana. He received a bachelor of science degree from Duke in 1953, then studied at the University of Cambridge before earning a Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley in 1962. He did postdoctoral work at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts before moving to Duke in 1964.

He was elected a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), and served as president of the American Society of Biomechanics in 1981, and the American Society of Zoologists in 1988.

Wainwright devoted more than 30 years to studying how the mechanical support systems of plants and animals help them move and protect them from impact, breaking and tearing.

By thinking in terms of mechanical design, Wainwright said, one could look at the structure of a shell, or a bone, or the rubbery stem of seaweed, and tell what kind of ocean waves its owner withstood, or how it might respond if conditions changed.

Wainwright’s main scientific contribution was in explaining how alternate layers of helically-wound fibers reinforce and streamline the body walls of many animals.

In a paper published in 1978 in the journal Science, he showed that sharks use a crisscross arrangement of collagen fibers in their skin as a flexible sheath to help them swim. His collaborations with colleagues and students revealed similar design features at work in the body walls of swimming dolphins and sea anemones, the movement of sea urchin spines and the mantles of squids.

In addition to his research, Wainwright was remarkably influential as a teacher and mentor.

In addition to his research, Wainwright was remarkably influential as a teacher and mentor.

In contrast to the khakis and button downs of most professors, Wainwright took the stage wearing flamboyant bow ties or Hawaiian print shirts.

“He also brought exuberant color to the biology he presented,” said professor James Tidball of the University of California, Los Angeles, who took several of Wainwright’s courses as an undergraduate in the early 1970s. “His creativity, enthusiasm and joyous pursuit of understanding the relationships between form and function were instrumental in creating novel ways of thinking about biology and had a tremendously positive impact on so many lives.”

Like his fellow biomechanics pioneer Vogel, who died in 2015, Wainwright encouraged his students to design and build 3-D working models to test their ideas.

Former Ph.D. student Mark Westneat, Ph.D. ’90, now at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, described his work with Wainwright as having two parts: “take fish apart to see how they worked, and then try to build one out of wood, clay, plastic and wire.”

“He gave me the nickname Carcass Marcus because I was always working with dead fish, with him by my side or peering over my shoulder,” Westneat said.

In his modeling, Wainwright “deliberately intersected with art, […] bringing fabrics and soft materials into the hands of physical scientists,” said Wainwright’s former graduate student John Long, Ph.D. ’91, now a biomechanics professor at Vassar College. “In this way, Wainwright was decades ahead of ‘new’ fields like soft robotics,” Long said.

In 1990, Wainwright co-founded with artist Chuck Pell the Duke Bio-Design Studio, which he called "the only art studio in an academic science department in the world.” Over 100 researchers worked there, “creating 3-D working models of everything from hand-woven whale blubber (it's fibrous, not just fat) to fully swimming and flying robots,” Pell said.

While Wainwright’s creativity will be remembered, so will his generosity and selfless support of early-career scientists.

“Steve notoriously did not seek out authorship on papers,” Long said. “Most of the time, he wanted to operate in the background and let his students and colleagues do the public performances and publish on their own, thus avoiding the appearance of riding his coattails.”

Wainwright’s approach was one of “supporting researchers rather than using them for self-aggrandizement,” Long said.

Long and Westneat recall one summer in the late 1980s when Wainwright took a group of students to Hawaii, renting a boat and scuba gear for a week so they could study the backbone-bending pattern of the 200-pound blue marlin, one of the fastest fish in the ocean.

He “quietly funded his students' ideas when no one else would or could,” Pell said. “He hated red tape, and would just buy equipment that a student could show was critical.”

“One of the things Steve Wainwright taught me,” said former graduate student Ann Pabst, Ph.D. ’89, of UNC Wilmington, was to “always sit lower than the person you are meeting with. This simple action, which puts your fellow at ease, and subtly tells them they are the most important person you could possibly be speaking with, encapsulates Steve,” Pabst said. “He did not say this to me -- he showed me.”

After he retired in 1996, Wainwright became a sculptor, carving his biologically-inspired sculptures out of massive chunks of wood that he hoisted with a crane into his home art studio, where he surrounded himself with books, bones, pottery, glass, toys, origami and fabrics.

He went on to establish several nonprofits and other ventures based in Durham. One, the Center for Inquiry-Based Learning, aims to help North Carolina K-8 teachers develop teaching practices that “nurture the natural excitement children have doing science.” He also founded SeeSaw Studio, a free after-school program for young artists that taught design and entrepreneurship skills to local teens.

“I have not met his equal in sensing the special talents of diverse individuals and gently launching and effectively supporting them as they defined and explored their separate domains,” Vogel wrote in 2007.

“His boldness in reaching beyond the normal disciplinary boundaries was remarkable,” said UNC-Chapel Hill biology professor Bill Kier, who earned his Ph.D. with Wainwright in 1983.

As Wainwright mentee Thomas Daniel of the University of Washington put it, “He was, in a sense, a Leonardo da Vinci of our generation.”