An interdisciplinary group from two universities is taking a data-driven approach to help protect North Carolina’s drinking water supply.

The Innovations in Infrastructure project is using the state’s drinking water systems as a lens to examine policies for better building and maintaining infrastructure necessary for delivery of basic public services. Funded by a multiyear Collaboratory grant from Duke University’s Office of the Provost, the project brings together Duke faculty and students with the Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“There are a lot of platitudes about an infrastructure crisis in the United States and sweeping indictments that list 20 problems to explain why our infrastructure is failing,” said co-principal investigator Megan Mullin, associate professor of environmental politics at Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment. “Our suspicion was that all of those 20 indictments hold, but they hold for different systems under different conditions. As long as we’re bundling everything together, we’re not going to be able to help improve infrastructure in particular places at particular points in time.”

Propose a CollaboratoryThe Collaboratory team has since narrowed its focus to policies affecting how drinking water is provided in North Carolina. As in much of the United States, it is “an expensive public service that’s supported locally and is extremely fragmented,” Mullin said. Some systems deliver water to just a few hundred paying customers. That is a small revenue base to support maintaining “capital-intensive infrastructure,” which can include building treatment plants, repairing or replacing aging pipes, or tapping new sources of water.

These water systems can face numerous challenges—increases or decreases in population, changing economic conditions, or impacts related to climate change, such as droughts or floods. How the local governments and utilities that operate these water systems see the risk from these challenges can differ from how the state or private sector sees them, said co-principal investigator Amy Pickle, director of the State Policy Program at Duke’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions.

“The overarching question for me is: How well does North Carolina assess the risks that impact the sustainability of local water supply and then prepare for those risks with either funding, education, or other policy solutions?” Pickle said.

They needed a critical piece of information, however, to get the right level of detail for the research.

“We have to understand the areas these water systems are serving, and no one knows that,” Mullin said.

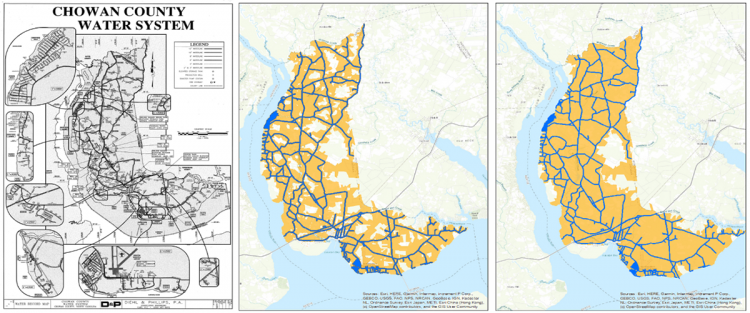

Like most states, North Carolina does not have a single digital map showing where every local water system is located. So the project team would have to build one.

To get started, the researchers turned to the North Carolina Division of Water Resources, which has become an invaluable partner in the project. In 2009, the General Assembly passed a law to help prepare for droughts that requires communities to submit water supply plans to the Division’s Bureau of Public Water Supply. As part of that reporting, the Bureau received PDF maps of service boundaries for each of the more than 500 community water systems in the state.

The trove of system maps came with varying degrees of quality. While some were generated with pinpoint accuracy by mapping software, many others were drawn by hand.

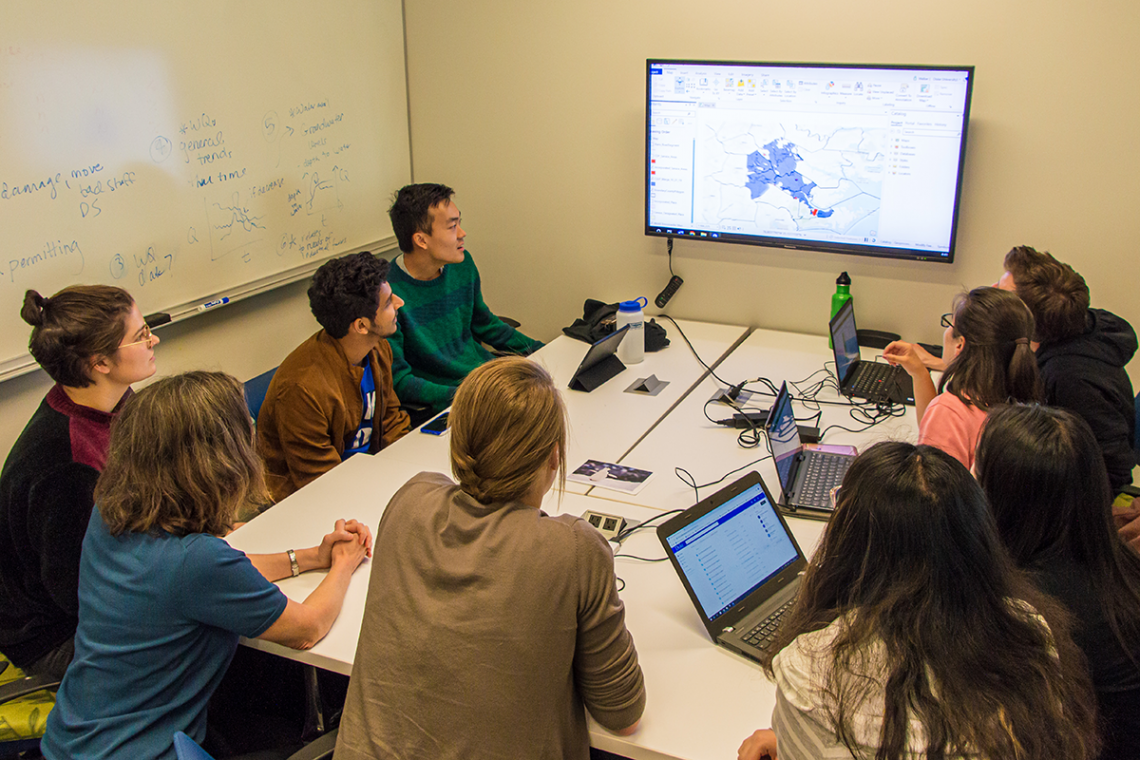

For more than a year, a team of eight student assistants from the Nicholas School of the Environment and the Pratt School of Engineering has been incorporating those system maps into a single digital statewide map. The challenging work gave the students an opportunity to learn new skills from each other, an important part of the educational component of the project.

“The team structure is amazing on an interdisciplinary level,” said Katy Hansen, a PhD student in the University Program in Environmental Policy who serves as the research lead for the project. “Lots of people are operating on the edge of their learning curves.”

The student team has been directed by Hansen and lead project manager Rachel Gonsenhauser, a master of environmental management (MEM) student in the Nicholas School. Bringing different backgrounds and levels of mapping expertise, they spent months refining a process for digitizing the water system maps. With a procedure in place, they have worked in pairs to incorporate the system boundaries into the larger map, checking each other’s work and sharing ideas as they go.

Kartik Pathak, a master of engineering management student in the Pratt School, is among the students who benefited from the pairs approach. Pathak came to the project with an interest in the topic but little GIS experience. His knowledge has grown from working with his “mapping buddy.”

Among the key members of the team has been Walker Grimshaw, who is working toward both an MEM degree from Duke and a master’s in environmental sciences and engineering from UNC. Grimshaw brought both GIS experience and an understanding of why the map was so vital based on his time with the Environmental Finance Center at UNC.

“I would keep meeting people who wanted what our end product will be—a tool showing where the water utilities are serving people,” Grimshaw said.

State agencies and researchers are excited to have that information, Mullin said. Once the students’ work on the map is complete, the Division of Water Resources will be able to go back to individual water systems to reduce any measurement errors in their boundaries. And this summer a new set of students will build an online tool to make that process easier for local governments and utilities, through Duke’s Data+ program.

Among the next steps for the project is an informal workshop in the spring with Division of Water Resources staff to go over the map and data related to risks that water systems are facing. The project team will also discuss policy innovations that can improve the flow of water supply information, both from local governments to the state and between different parts of the state bureaucracy.