Agree to Disagree: Teaching Students to Depolarize

Undergraduates learn to get to know others and why they believe as they do

Duke is expanding a multi-faceted effort aimed at equipping students to respect differing viewpoints. This new Duke Today series examines the decline in civil discourse and Duke’s efforts to improve campus dialogue.

See the full series

Wearing a red Make America Great Again hat and a white trash bag with two holes cut out for sleeves, Brendan Dickson takes a seat at the end of a long rectangular table before class starts in the West Duke building.

It’s midmorning on Halloween, and the first-year student is trying to prove that conservatives aren’t treated unfairly on Duke’s campus.

“My faculty-in-residence is pretty conservative,” Dickson says. “He’s always going on that you never see any Trump hats on campus, and he’s convinced that means conservatives are made to feel unsafe about their opinions.”

Fellow first-year student Thomas Mande takes issue with the experiment.

“You’re saying conservatives aren’t oppressed, but then you’re ripping conservatives,” Mand says. “Why are you doing that? I don’t think it’s cool. I’m being offended on behalf of people talked about as white trash. These are people, and then you’re out here mocking them at one of the most privileged institutions in the country.”

“Right, I think it’s good to laugh at yourself,” Dickson says.

“Right,” counters Mand, “but you’re not these people.”

Welcome to “Virtuous Thinking in an Age of Political Polarization,” a Kenan Institute for Ethics/political science course for first-year students that’s among Duke’s efforts to help students deal respectfully with those who hold opposing views.

Kenan Institute instructor John Rose is challenging his students to go beyond “self-segregation,” the practice of associating only with those who share your beliefs.

“Our motto is ‘Truth, not victory,’” Rose says in an interview. “Students with the minority view need to feel comfortable. Absence of that is making society more polarized, and it’s counter to the spirit of a liberal arts education.”

Using a mix of moral philosophy with social and political science literature, Rose’s course examines the current phenomenon of political “partyism” and cultural segregation. He urges students to “rise to the occasion” -- get to know people and why they believe as they do.

Class topics include “The Culture of Contempt,” “The Value of Intellectual Diversity” and “The New Tribal Left and Right, Racism and Bigotry.”

“It really teaches them how to disagree well,” says Rose, who is also associate director of the ethics-promoting Arete Initiative at Duke. “Our class tries to transcend tribalism and find common ground.”

Students say that the class is doing just that.

“I've learned how to interact with others of different beliefs and how to express my views in a logically sound way,” says student Julia Feldman. “I now also understand the significance of being able to back your opinion and accept others’ opinions, regardless if I agree or not.”

“I have learned how to both understand and analyze viewpoints and situations with an open mind and be cognizant of the many differences between people,” adds student Charles Shaffer. “I have also learned that we must be accepting of others -- this does not mean we must agree with them on everything -- in order to avoid polarization and help increase intellectual diversity.”

Preparing undergraduates to become more tolerant voters and citizens couldn’t come at a better time.

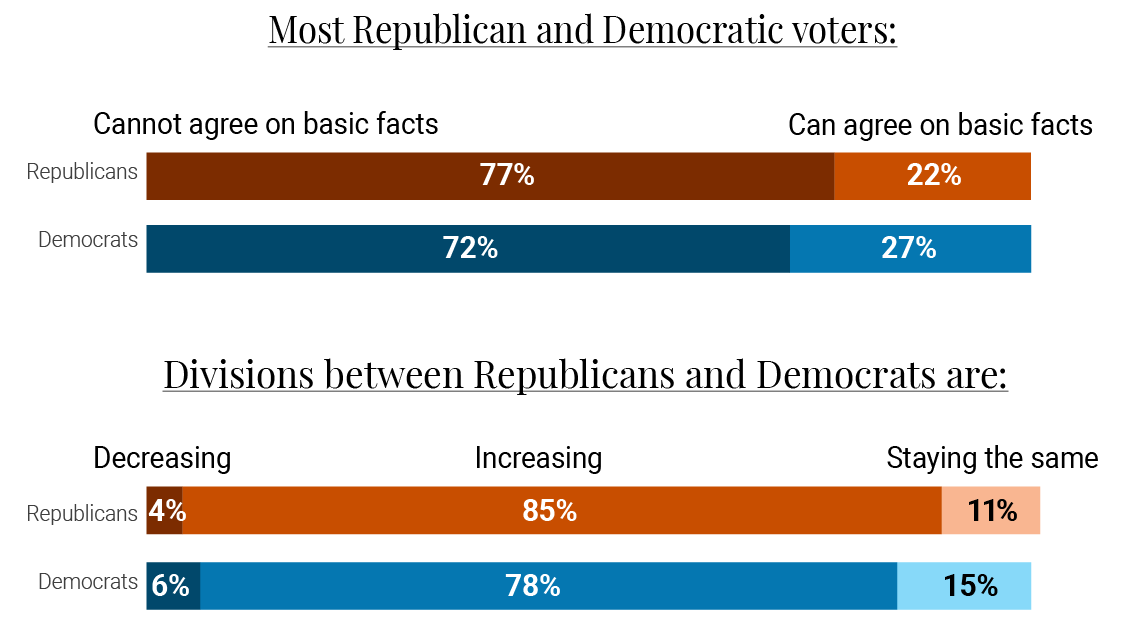

A Pew Research Center study released in September found that 85 percent of Republicans and 78 percent of Democrats believe divisions between the two parties are increasing. Further, Republicans (77 percent) and Democrats (72 percent) say they can't even agree on “basic facts.”

On a recent Tuesday morning, two leaders from a group that works to break down such partisan barriers make their case to Rose’s class.

Better Angels sponsors workshops and other events across the country to help people move beyond a disdain for those on the other side of their political ideology. The goal is not to change political positions, but to help people better understand those with whom they disagree.

“I don’t think people change their views, but change their view of the other side,” says John Wood Jr., Better Angels’ director of media development who as a Republican unsuccessfully ran for Congress in 2014 against Maxine Waters in Los Angeles.

“There is an appetite for what we’re doing, but there is a fear and I think it often comes from their own tribe,” adds Ciaran O’Connor, Better Angels’ chief marketing officer and a 2013 Duke graduate. He worked as a staffer on the Obama 2012 and Clinton 2016 presidential campaigns.

The media – especially tribalistic social media – helps feed the partisan beast, they say.

“Things are going to get worse before they get better,” O’Connor says. “For the media and pols, outrage and fear sells. Facebook and Twitter don’t reward restraint, they reward trying to humiliate people.”

A 2018 study by the Duke Polarization Lab, run by sociologist Chris Bail, found that exposing social media users to opposing viewpoints actually increased the division rather than boost an understanding of one another.

Another effort promoting political understanding is the Bipartisan Political Dialogue Program through Duke’s Center for Political Leadership, Innovation, and Service (POLIS). The monthly conversations among roughly 10 students from conservative, liberal and moderate persuasions gather to talk about today’s most contentious political issues, including gun control and free speech.

“Participants are learning to understand perspectives which differ from their own and growing their ability to meaningfully engage in these types of conversations,” says senior Elliott Davis, who started the program.

He got the idea for the POLIS program after studying abroad at a cross-border environmental peacebuilding institute where Israelis, Palestinians, Jordanians and internationals learned about each other’s political perspectives and became friends during the process.

“I hope this program will continue to teach rising political leaders the values of civility, diversity and dialogue for years to come,” he says.

Back in Rose’s class, students are debating Google’s 2017 firing of an engineer whose internal memo criticized his employer for its efforts to boost gender and racial diversity among workers. James Damore’s memo attributed a lower number of women in tech to psychological differences between men and women, and called for a more collaborative and caring software engineering culture. He has since sued Google.

A majority of the roughly 15-member class does not believe Damore should have been fired, with some noting he intended for the memo to remain internal.

“Is he stereotyping?” Rose asks the class.

“He’s not saying that if you possess these evidenced-backed female qualities that you can’t do your job,” says student Lily Vore. “He’s saying right now, the culture in tech is not conducive to those female qualities and that we should change that culture and that environment to make it more conducive for females to thrive.”

After class, Vore says she attended a high school where students were very politically active and very polarized. Rose’s class has improved her ability to tolerate opposing viewpoints, she says.

“I wouldn't say I wasn't understanding of those with whom I disagree before this class,” she says, “but I would say that by interacting and discussing difficult, significant topics in a respectful, informed manner, my ability to weigh other perspectives and modify my own thinking has definitely improved.”

Katherine Zheng, a first-year student from Vancouver, Canada, says she had no idea what polarization was until taking Rose's class.

"This class has definitely helped me understand others’ views," she says, "because it was a safe space where everyone could actually properly explain themselves and have positive debate about each others’ perspectives."