The Offices Where Great Things Happened

On a campus where time rarely stands still, historic spots go on to have new lives

At first glance, Tom Brothers’ office in the Biddle Music Building isn’t particularly remarkable. It has a few windows, filing cabinets and a desk.

Near the door, there’s a Steinway piano that Brothers, a professor of music and jazz scholar, said was in the office when he moved in about 10 years ago. When asked if the piano had been there long enough to be played by his office’s most famous inhabitant, Mary Lou Williams, Brothers smiled.

“Probably not, but who knows?” he said.

To most people, office 071 in the Biddle Music Building is no different than any of the other workspaces tucked into the building’s ground floor. But 40 years ago, the space was home to Mary Lou Williams, a ground-breaking jazz talent who spent her final years sharing her expertise with Duke students.

On a campus where students turn over every few years and the work of teaching, learning and searching for answers continues each day, many spaces go on to have new lives, leaving their ties to important pieces of Duke’s past largely unnoticed.

Here are the stories of three such campus places, largely anonymous spots where important chapters of Duke’s history unfolded.

Residual Karma

Wiley Schell, an associate professor in the Duke University School of Medicine, said that scientists don’t often get sentimental about their workspaces. If their labs and offices are well-equipped and big enough, that’s all that matters.

For the last five years or so, the third floor of the Sands Building has been home for Schell and his colleagues in professor John Perfect’s lab, which studies fungal infections.

“It’s been a good space for us,” Schell said.

The third floor of the Sands Building has been good for other Duke researchers, too.

The third floor of the Sands Building has been good for other Duke researchers, too.

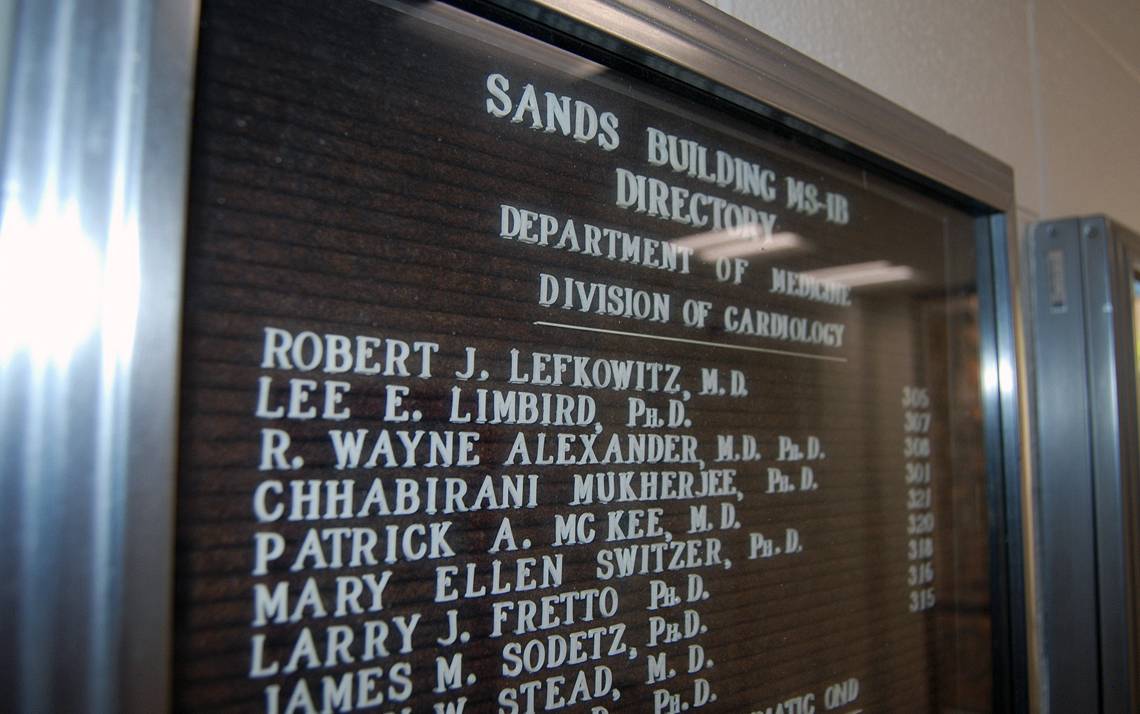

In 1973, when the building opened, one of its first tenants was new Duke faculty member Robert Lefkowitz. Over the next several years, Lefkowitz and his team unraveled the mysteries of how proteins work together, opening doors for drugs that addressed conditions ranging from allergies to heart disease.

In 2012, Lefkowitz earned the Nobel Prize in chemistry, becoming the first Duke professor to win the award. By then, Lefkowitz and his team moved into the nearby Clinical and Research Laboratory Building, where he has a larger office with a small drawback.

“I used to have a beautiful view of the chapel,” Lefkowitz said of his Sands Building office. “If it was a really rainy stormy day, you could watch the clouds descend, and you’d lose the ability to see the top of the chapel. It was great.”

Schell, who now inhabits Lefkowitz’s old office, has that view now. And while he and his colleagues go about their work without dwelling on what once happened in their workspaces, Schell admitted that the history of his workspace is too fun not to acknowledge.

“When we moved in we kind of joked about it,” Schell said. “We hoped that there was some residual karma or creative forces hanging around in the room.”

Literary Echoes

Ranjana Khanna, professor of English and Women’s Studies, recalls going to a recent Rubenstein Library exhibit of items belonging to former Duke professor and acclaimed author Reynolds Price. Khanna spent several years as a colleague of Price, who died in 2011 and said it was especially moving to hear recordings of Price’s booming, yet graceful southern accent.

“He was great to be around, he was lovely to me, always very warm and with a wicked sense of humor,” she said.

Working from her office on the third floor of the Allen Building, Khanna never has to go too far from reminders of Price. From 1993 until his death, Price worked out of the office Khanna has now.

Price joined the Duke faculty in 1958 and built a formidable literary legacy as a novelist, essayist, poet and playwright, exploring life in the south and the complicated nature of faith. This made him one of the most prominent figures on campus and turned his office into a destination for both students and celebrities. Longtime English department staff members recall Grammy-winning singer-songwriter James Taylor, Price’s friend and collaborator, as a regular visitor.

Price joined the Duke faculty in 1958 and built a formidable literary legacy as a novelist, essayist, poet and playwright, exploring life in the south and the complicated nature of faith. This made him one of the most prominent figures on campus and turned his office into a destination for both students and celebrities. Longtime English department staff members recall Grammy-winning singer-songwriter James Taylor, Price’s friend and collaborator, as a regular visitor.

These days, the room which contained Price’s office is quieter. Khanna, who is also the director of the Franklin Humanities Institute, does most of her writing and takes most of her meetings in the front room of the two-room suite. Here, she works beneath towering bookshelves and a colorful, wall-sized collage celebrating the reach and legacy of Bob Marley.

But it’s the rear space of Khanna’s office, where Price worked, that’s especially stunning. A bank of large windows – complete with gothic-revival ornamentation – looks out onto Abele Quad. In the space that Khanna uses to do research and formulate lesson plans, she has a sofa, bookshelves and table which holds a small kettle and several tins of tea.

The space is distinctly hers, but she said the happily shares it with the ghosts of Price.

“It’s just very nice to have that sense that he was in here and that the office treated him well,” Khanna said.

Home of Greatness

As director of Duke’s Mary Lou Williams Center for Black Culture, Chandra Guinn often runs into people who were Duke students during the four years when Mary Lou Williams was on the faculty. And without fail, their memories of working with her are both happy and vivid.

“You could tell she really cared,” Guinn said. “I’ve heard people say she treated them with a warmth and regard that made them feel seen.”

Williams taught in the Duke Music Department from 1977 until her death in 1981. An acclaimed pianist, composer and bandleader with a list of friends and collaborators that included jazz icons such as Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, Benny Goodman, Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, the opportunity to work with Williams was a unique thrill for the Duke students and faculty members in her orbit.

Williams taught in the Duke Music Department from 1977 until her death in 1981. An acclaimed pianist, composer and bandleader with a list of friends and collaborators that included jazz icons such as Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, Benny Goodman, Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, the opportunity to work with Williams was a unique thrill for the Duke students and faculty members in her orbit.

The center of that orbit was her office, office 071, which now belongs to Tom Brothers, on the ground floor of the Biddle Music Building.

With jazz fans and music scholars gaining more of an appreciation for her work, Williams legacy has grown since her death. In 1983, the Mary Lou Williams Center for Black Culture opened at Duke. The Mary Lou Williams Jazz Festival is now held each year at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C.

“Her legacy extends across decades,” Guinn said. “She was an innovator in a way that people who care about music really appreciate and have deep respect for.”

But her office, which has changed hands a few times in the past few decades, is a small reminder of her time at Duke. And working there is something that Brothers takes pride in.

“I just have a lot of respect and appreciation for her and for what she did in her life,” Brothers said. “It’s very nice to feel connected to that.”

Got a special office? Send email to Working@Duke.edu.