An Inside Look at Duke's Finances

From the Great Recession to current fiscal realities, Working@Duke demystifies Duke's finances

Inside research greenhouses on West campus, string bean plants and Morning Glory vines shoot skyward, toward the sunny glow of overhead lights. Near many, small signs bear the names of Duke professors studying them.

Elsewhere in the greenhouse operated by the Department of Biology, plants are labeled with bar codes, showing the plants belong to outside entities renting the unused space.

The idea to earn money off extra greenhouse space took root about a decade ago, when Duke faced a $100 million budget shortfall during the economic downturn of 2008-09 and university departments responded by finding ways to save money. While adhering to federal research regulations and maintaining the university’s non-profit status, the greenhouse is able to use revenue from unused space to offset operating expenses.

“It was like, ‘We’re all in this together. Let’s try to find a way to survive it,’” said Randy Smith, the manager of Duke’s Department of Biology who suggested the idea to lease the space.

“It was like, ‘We’re all in this together. Let’s try to find a way to survive it,’” said Randy Smith, the manager of Duke’s Department of Biology who suggested the idea to lease the space.

In 2008, the nation experienced the largest economic downturn since the Great Depression. The U.S. Treasury estimated 8.8 million jobs were lost and $19.2 trillion in household wealth disappeared during the recession, which also shook Duke.

The Duke University endowment – the pool of invested money that’s the financial backbone of the university – suffered a 24.5 percent loss. Meanwhile, Duke University leadership and departments found ways to cut around $75 million in annual spending.

While Duke managed the recession with responsible stewardship, many community members are not aware of the long-term effects, or of Duke’s financial realities and structures today. Duke has a strong balance sheet and ample resources to fulfill its mission, but with financial experts predicting another recession in the coming years, it’s important to understand the factors that limit Duke’s financial flexibility.

“The reality is that Duke is blessed with significant resources, yet our community members constantly experience pressure due to resource constraints,” said Tim Walsh, Duke’s vice president of Finance. “This is essentially because the vast majority of our existing resources are restricted as to use, and because there are always many ambitions across Duke to do new and exciting things.”

“Major things ... don’t make money”

Debra Silver, associate professor for Duke Molecular Genetics and Microbiology, is fascinated by what happens as brains develop. Cells divide and connect, sketching the unique blueprint of someone’s mind.

Long, skinny neural stem cells drive the process, creating the web of neurons that communicate with the body. If they don’t create the right types of neurons at the right time, it can lead to diseases such as autism.

When Silver, who came to Duke in 2010, found factors that might alter neural stem cells’ behavior, she wanted to dive deeper.

“It was a completely new research direction,” she said.

Without external grant funding for this project, Silver was awarded $125,000 in bridge funding from Duke, which supports Duke faculty members whose promising research that has yet to secure external funding.

“It shows that Duke is willing to invest in the people who are doing good research,” said Silver, whose work on this project has since earned two government grants.

While bridge funding spurs innovation and empowers researchers, it costs money. Government and private sources fund the majority of the university’s research, but Duke typically spends between $100 to $150 million per year to cover remaining costs, which includes bridge funding.

Walsh points out that virtually all of Duke’s activities – including education and research – operate at a loss, which is not unique to Duke or higher education.

“The major things we do,” Walsh said, “simply don’t make money.”

For example, he explained, the “list price” for an undergraduate education, including tuition and living expenses, is about $75,000, but the cost of providing the undergraduate student experience at Duke is estimated to be approximately $125,000 per student. Furthermore, with Duke providing financial aid to about 50 percent of its undergraduate students, the university collects an average of around $42,000 per undergraduate.

In the current academic year, Duke will invest more than $175 million in undergraduate financial aid.

“In many ways, we’re trying to scrape together money for new things because of the disconnect between what we actually collect and what we actually spend on our students,” Walsh said. “And that's true at almost any research university.”

However, Duke’s strong investment base, generous donor base, and support received from Duke University Health System for the research mission keep the university on firm financial footing.

“Need for cost-consciousness”

When Sharon Kinsella arrived at Duke, she planned on majoring in biology.

But after joining the Hoof n’ Horn musical theatre group, she found her passion: the arts. Now a Global Cultural Studies major, she’s performed in and produced Hoof n’ Horn musicals, and sees her future in the arts.

As living proof of the vitality of Duke’s growing arts scene, Kinsella, now a senior, gives tours of the Rubenstein Arts Center to prospective students who, like her, didn’t realize the role arts play on campus.

“It’s cool to show them that ‘Yes, there is a place for you,’” Kinsella said.

The Rubenstein Arts Center, which opened in 2018, is a campus-wide destination for the study and production of the arts. It features studio spaces, a 200-seat theater, film theater, radio studio and high-tech makerspace.

“It’s a beautiful building,” said Marcy Edenfield, senior director of the Rubenstein Arts Center. “It gives students a home base, a location where they can make art happen.”

The building is also an example of how money that flows into Duke is often tied to a specific priority and cannot be used for other expenses. In 2015, a gift from philanthropist and Duke graduate David Rubenstein spurred the creation of the Rubenstein Arts Center at a cost of $50 million.

The money spent on the Rubenstein Arts Center – as well as other new construction such as the Karsh Alumni and Visitors Center and the Hollows Residence Hall – was part of $305 million in Duke’s capital spending in 2018. Financed mostly with debt and gifts, Duke’s new buildings

The money spent on the Rubenstein Arts Center – as well as other new construction such as the Karsh Alumni and Visitors Center and the Hollows Residence Hall – was part of $305 million in Duke’s capital spending in 2018. Financed mostly with debt and gifts, Duke’s new buildings  aren’t part of the university’s operating budget, which was $2.86 billion last year with salaries, wages and employee benefits representing nearly 60 percent of that budget.

aren’t part of the university’s operating budget, which was $2.86 billion last year with salaries, wages and employee benefits representing nearly 60 percent of that budget.

Duke University’s endowment – now valued at over $8.5 billion – provides around $500 million per year to support university operations. But virtually all of the endowment comes with stipulations and must go to specific purposes spelled out by donors.

While Duke has considerable resources to fulfill its mission, finding unrestricted money to devote to new priorities can be a challenge.

That becomes an issue in lean times, such as the 2008 financial crisis. Before the downturn, Duke had around $800 million in unrestricted funds in its endowment. Between the falling value of investments and the withdrawal of around $250 million of those reserve funds (or its rainy-day fund) to finance university priorities following the crisis, Duke lost or used more than half of the unrestricted money in its endowment.

With a Fuqua School of Business survey of corporate financial officers suggesting that a recession is likely by late 2020, Duke would have far less financial flexibility during another recession.

“The need for cost-consciousness across Duke will be as urgent as ever in the coming years,” Walsh said, “with or without another financial downturn, if we are going to fully execute on the many ambitions of Duke.”

“Retail with a higher purpose”

On the Friday before 2019 commencement, Willie Williams watches a flood of shoppers in the University Store rush between racks of Duke jackets, hats and jerseys, clutching the keepsakes they’ll soon buy.

Williams, who has worked for Duke University Stores for 31 years and is an assistant general manager, knows how to keep this busy day from turning into chaos.

“We call ourselves coaches,” Williams said of his team. “We’ve put together a game plan for how all of this is going to work. We’ve got all our positions laid out.”

For the rest of the afternoon, customers flow to registers, buying reminders of the university they hold dear. And each purchase helps Duke function a little easier. With 14 locations across campus selling an array of items such as snacks, school supplies, computers and thousands of Duke-branded garments and gifts, Duke Stores is one of the university’s handful of profit-generating units.

For the rest of the afternoon, customers flow to registers, buying reminders of the university they hold dear. And each purchase helps Duke function a little easier. With 14 locations across campus selling an array of items such as snacks, school supplies, computers and thousands of Duke-branded garments and gifts, Duke Stores is one of the university’s handful of profit-generating units.

In the past fiscal year, Duke Stores brought in around $25 million in gross revenue. After covering operating expenses and the cost of goods, Duke Stores contributed $6 million to the university’s operating budget.

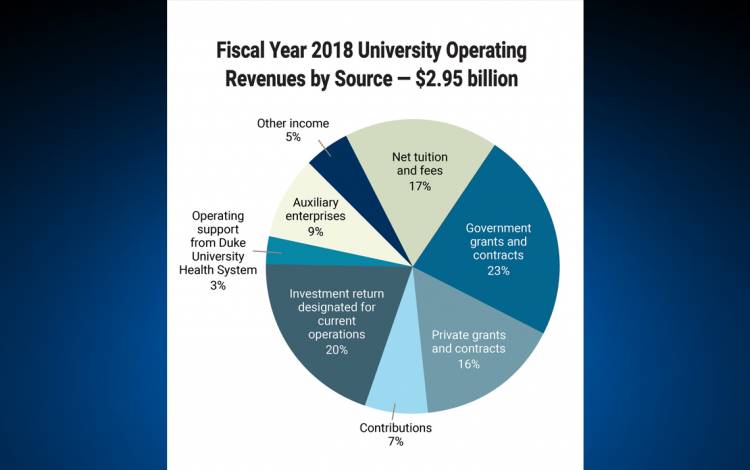

Only 9 percent of Duke University’s total $2.95 billion in operating revenue comes from “auxiliary enterprises,” such as dining services, parking and transit, and retail operations such as Duke Stores. But in the context of how resources are allocated at Duke, the contributions loom large.

Duke University’s budgeting structure is driven by individual academic schools, which earn or are allotted money to cover their needs and commitments. A portion of their resources must be devoted to central administration costs such as maintaining infrastructure and paying wages and benefits for roughly 2,750 central administration employees who keep campus running.

The revenue from sources such as Duke Stores goes directly to covering central administration expenses, easing the financial load on schools and leaving schools better positioned to fulfill their mission.

“I call it retail with a higher purpose,” said Jim Wilkerson, Duke Stores’ director of trademark licensing and stores operations. “It’s retail within an institution that utilizes our dollars to support its goals and priorities for education, health care, research and doing good for society across the world.”

Have a story idea or news to share? Share it with Working@Duke.