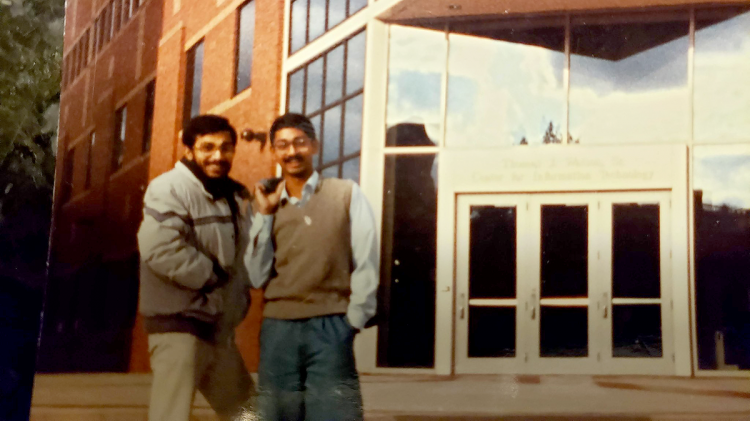

On Aug. 26, 1989, Ravi Bellamkonda flew from India to the United States, where he didn’t know a soul.

“I had never been on an airplane before,” he said. The 21-year-old had a spot in grad school at Brown University in Rhode Island, and $800 in cash to live on until his fellowship kicked in.

Thirty years later, Bellamkonda is a pioneering biomedical engineer, dean of Duke’s Pratt School of Engineering and a U.S. citizen. His journey as an immigrant and a scientist has shaped both who he is and the importance he attaches to training the engineers and leaders of the future.

Thirty years later, Bellamkonda is a pioneering biomedical engineer, dean of Duke’s Pratt School of Engineering and a U.S. citizen. His journey as an immigrant and a scientist has shaped both who he is and the importance he attaches to training the engineers and leaders of the future.

“The world is not already made, it’s not a system you just have to figure out,” he said. “We as individuals can help create and shape this world, whoever we are.”

As a boy, Bellamkonda hoped to be a doctor, but found biomedical engineering combined his interests in math and medicine.

“It was made for me,” he said.

When he arrived in the U.S., Bellamkonda stayed for a week with two German brothers he’d never met, computer scientists, who took him in just because he was the friend of a friend of a friend. Then he found a roommate who covered his half of the deposit for an apartment until his fellowship started paying.

”It was tight, that first month,” he said. “There were many people who were very kind to me.”

Bellamkonda had no plans to stay in the United States after school. He didn’t even intend to complete a Ph.D. Then he had what he now calls a revolutionary moment -- when he asked his graduate adviser a research question and was told no one knew the answer, and that he should design an experiment to find it himself.

“The idea that nobody in the world knew this thing – it was about how to grow brain cells in gel – and that someone like me, who didn’t even know if I wanted to be a scientist, could design an experiment to find out, was mind-boggling to me,” he said. “It showed me what a leveler science is – that a student could find out something nobody knew.”

“ When we’re young, we think about what we want to be – a doctor, a scientist, an entrepreneur – but not enough time thinking about who we want to be. We need to keep track of that, too. You have to be anchored on the inside, and not the outside.”

-- Ravi Bellamkonda

Today, he studies brain cancer, which typically spreads before it’s diagnosed, making it impossible to remove. So Bellamkonda’s work focuses on how cancer cells in the brain can be moved. His team created a tumor monorail, a filament that mimics the nerves along which brain cancer cells tend to travel, which lures the cells to the edge of the brain where they can be neutralized. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has named it a “Breakthrough Device.”

He’s also experimenting with electrical fields that can nudge the cells to move in a certain direction, and with tumor-seeking bacteria that are drawn to brain cancer cells and can kill them where they are.

“Brain cancer survival rates haven’t changed since 1968, simply because the cancer cells move around,” he said. “As an engineer fooling around with a serious thing like cancer research, I’d rather be out of that business, but all ideas are welcome until we figure it out. Patients don’t have the luxury of time to wait.”

His desire to contribute – and the ability to effect change – was what spurred Bellamkonda to look beyond the classroom and lab and toward a leadership role, where he could help shape curriculum and learning experiences.

“When we’re young, we think about what we want to be – a doctor, a scientist, an entrepreneur – but not enough time thinking about who we want to be,” said Bellamkonda, who came to Duke in 2016 to lead Pratt. “We need to keep track of that, too. You have to be anchored on the inside, and not the outside.

“If you want to be a doctor, you know what courses you need to take. But what do you need to do to become the person you want to become? Maybe it will just happen, but this is too important to be left to chance. Whether that comes from spirituality, music, reading – there are many ways to get there -- but we need to be intentional about doing things that nourish our soul.”

Moving to the U.S. – and later becoming a U.S. citizen – was part of Bellamkonda’s version of that journey.

“Giving up your nationality is a big deal,” he said. “I have deep gratitude toward India for investing in me. At the same time, I live here and I felt strongly about contributing my voice to shaping what America is, and what it will become.

“As an immigrant you tend to look at the system afresh. The American idea is powerfully aspirational and noble, and I didn’t want to cede the definition of what it could be – because it is being written still – to those I didn’t feel were interpreting it the right way. I wanted to actively add my voice to shaping what it is, and what it becomes.”

That is why it’s so important to Bellamkonda to help students be centered while living and studying in a country that offers so many choices that it can sometimes seem overwhelming.

“When I arrived, it was assumed there would be other Indian students who would be my friends,” he added. “And some of them did become close friends, but my closest friends were not all of Indian origin. In the U.S., we have a melting pot with people from everywhere, and the people you resonate with can be from anywhere. It was a powerful realization for me that when we say ‘us,’ we can mean anyone.”