Mary or Martha?: A Duke scholar's research finds Mary Magdalene downplayed by New Testament scribes

A 12th century Greek manuscript in Duke's library helps religion doctoral student Elizabeth Schrader argue her case

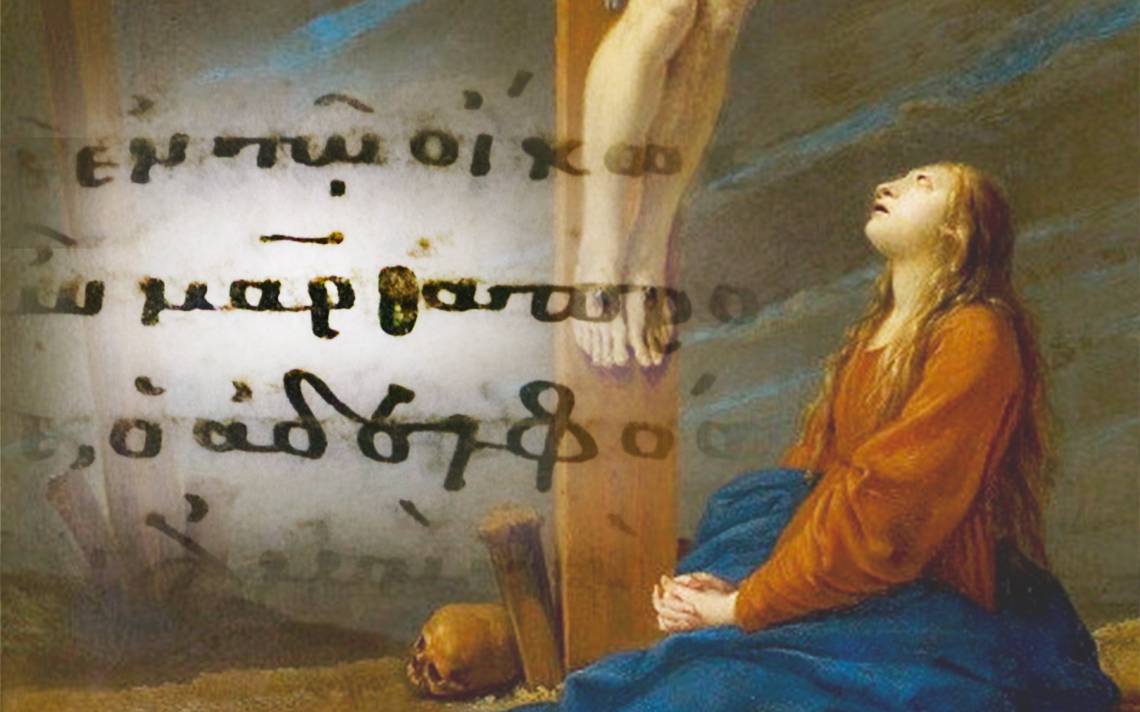

Looking closely at a digital image of Papyrus 66 - generally thought to be the oldest near-complete manuscript of the Gospel of John - Elizabeth Schrader noticed something odd.

The word ‘Maria,’ (or Mary) had been altered, with the Greek iota symbol – the ‘i’ –scratched out and replaced with a ‘th’ that changed the name to ‘Martha.’ And in a later verse, a woman’s name was replaced with ‘the sisters.’

This discovery was the first of many that Schrader, now a Duke doctoral student in religion, would make. She did so by poring over hundreds of transcriptions of these manuscripts that represent the work of so many scribes who hand-copied versions of the Bible; some of these scribes made slight changes along the way.

The discovery, Schrader argues, points to a deliberate minimizing of the legacy of Mary Magdalene, the controversial follower of Jesus who witnessed his death, burial and resurrection.

Schrader’s findings were published in the scholarly journal Harvard Theological Review two years ago; since then, she’s found even more evidence supporting her core claim that the text of John was altered early on, including one 12th-century manuscript in Duke’s Rubenstein Library archives where ‘Mary’ has again been replaced by ‘Martha.” (Martha is a biblical figure described in the Gospel of Luke.)

“Elizabeth has called attention to a problematic and significant variant in an urgent new way,” said Jennifer Knust, a Duke religious studies professor and Schrader’s doctoral advisor. “That alone is important — and she is the first to put the pieces of this puzzle together.”

Schrader understands her claim is provocative because it could undermine foundational assumptions about the Gospel of John, one of four gospels of the Christian Bible.

But some Biblical scholars are intrigued. In July, Schrader will visit the editors of the Nestle-Aland New Testament, the edition of the Greek text used by most scholars, students, and translators today and also employed in United Bible Societies’ editions. The Nestle-Aland New Testament is regularly updated to reflect the most up-to-date knowledge in the field about the earliest recoverable text. Schrader’s findings may warrant a mention in the critical apparatus that will accompany the edition under preparation now.

Here, she discusses her work with Duke Today.

You’re meeting in July with editors for the Nestle-Aland and UBS Greek New Testament, which publishes new pocket editions for scholars with footnotes and updates based on ongoing scholarly interpretation of the Bible. If they cite your research, what does that mean?

If the editors decide to update the printed initial text or the critical apparatus based (at least in part) on my work, it would be a formal acknowledgement for all scholars of the New Testament that there is a problem with Martha in the textual transmission of John.

To be clear, you’re arguing that Martha was not originally in the Gospel of John but has been added as a way to replace Mary Magdalene?

I’m arguing that Mary Magdalene’s original role in the Fourth Gospel has been divvied up, so that she now appears as three women in John. I’m not arguing that Martha didn’t exist - she definitely belongs in the Gospel of Luke. But I do not believe she belongs in the Gospel of John. There’s too much manuscript evidence, where problems appear around Martha in nearly every scene in John in which she appears. You have to look at over 200 manuscripts at once to see this trend; only recently have hundreds of transcriptions of the Gospel of John been made available simultaneously online. I believe that’s why this evidence was overlooked previously.

When you say ‘a problem around Martha,’ what precisely do you mean?

It manifests in lots of different ways. The most obvious one is what we have at Duke. The name ‘Mary’ has been changed to ‘Martha’ at John 11:21. It can also appear in the form we see in the first printing of the King James Bible, where only one sister is mentioned in John 11:3, whereas a modern Bible would have two sisters in that verse. And in Papyrus 66, the oldest copy we have, there are problems with Martha in five verses straight. One verse has a ‘Maria’ changed to ‘Martha,’ and in another, it appears that the name ‘Maria’ is changed to ‘the sisters,’ altering one named woman into two unnamed women.

And why would these changes have been done?

I believe this was done to distort the Gospel of John’s presentation of Mary Magdalene. If Lazarus’s sister Mary is Mary Magdalene, then she becomes a far more authoritative figure in the Gospel of John. However, once Martha is added to this story, Lazarus’ sister Mary isn’t Mary Magdalene anymore - instead she’s a different Mary from a different gospel (Martha’s sister from Luke 10). We know from other early Christian texts that Mary Magdalene was a controversial figure in earliest Christianity. I think somebody was trying to downplay her prominence. The Gospel of John is a central text of Christianity, and I believe it intended to give Mary Magdalene a very prominent role. But she may have been just too much for the time.

So what damage does all of this do to the legacy of Mary Magdalene?

It distorts her presentation and dilutes it. It makes her one of many women interacting with Jesus, as opposed to her being a prominent figure in the entire second half of the Gospel of John.

It distorts her presentation and dilutes it. It makes her one of many women interacting with Jesus, as opposed to her being a prominent figure in the entire second half of the Gospel of John.

Of course in modern Bibles, she’s still there at the cross and still the only person Jesus appears to Easter morning in the garden. She has always been famous for that. But Mary Magdalene is now one of several important women in the Gospel of John who have significant interactions with Jesus - and I think that some of those interactions were hers alone originally. For example, in modern Bibles Martha gives the central faith confession of the Gospel of John: “Yes, Lord, I believe that you are the Messiah, the Son of God, the one coming into the world” (John 11:27). But according to the church father Tertullian, who wrote in about 200 CE, that confession was Mary’s.

You’re a Christian. Does this do anything to your own faith or belief system as it relates to this section of the Bible?

This actually strengthens my faith. It shows me that the earliest version of the text was friendlier to Mary Magdalene. It was those who copied it who had a problem with such a strong woman. It gives me faith in God: from my perspective, God has preserved evidence in these manuscripts for us to find.