Walt Whitman Was a Rebel, And It Still Matters Two Centuries Later

Brodhead returns to Duke to celebrate 200th anniversary of famed poet's birth

Walt Whitman’s formal education didn’t extend past the fourth grade; his youth in Brooklyn was marked by financial instability and uncertainty. As an adult, he first scratched out a living as a carpenter, typesetter, printer and editor before deciding that he had a calling to be a poet. That’s not a resume of an author about to set the world on fire.

But if that poetry seems unremarkable to the contemporary reader, President Emeritus Richard Brodhead told a Perkins Library audience Thursday, it’s only because we fail to see that Whitman threw out all of the rules of poetry of his time. The event celebrated the 200th anniversary of the poet's birth year.

For 45 minutes, Brodhead returned to campus in “throwback mode” as a scholar of American literature and led a master class on Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass.” First published in 1855, the book was repeatedly reworked and expanded by Whitman throughout his life.

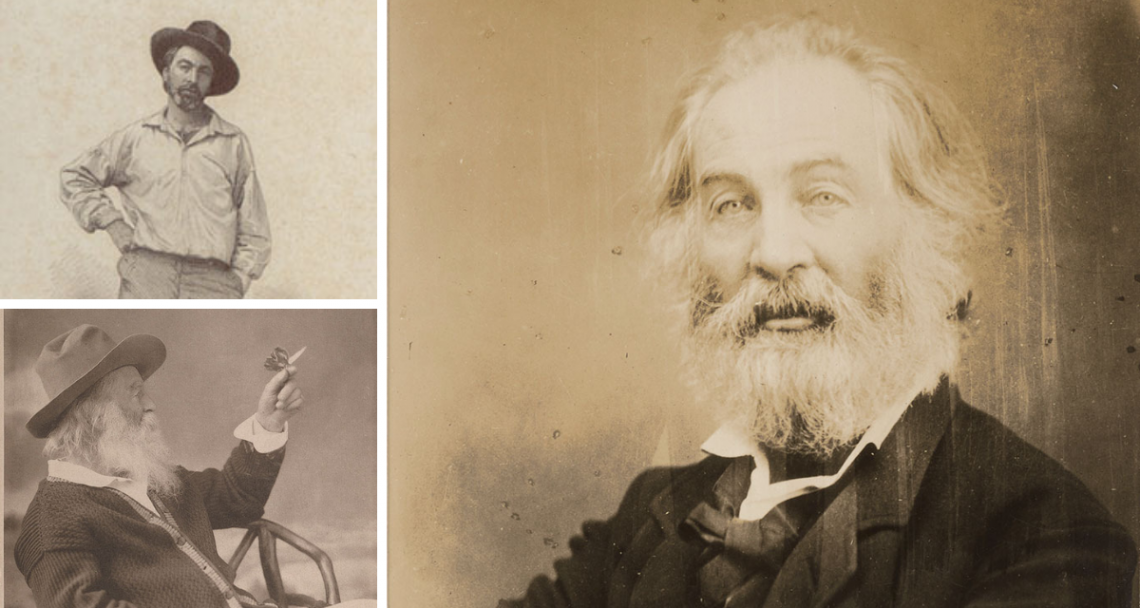

The work was revolutionary, Brodhead said —“and we are on the other side of the revolution Whitman effected.” Out went the dictates of meter and rhyme. No more were the formal rules of accents and stress. The first edition didn’t even have an author’s name listed on the title page – just a photograph of the author in a casual, slouching pose. Whitman’s message, Brodhead said, was “This book is me.”

“I’ve never before or since read anyone try to describe the experience of vitality taking place inside you,” Brodhead said. “What does it feel to have blood being forced through your veins? What is it like to have air flowing in and out of your body? What does it feel like just to be alive?”

Brodhead captured Whitman’s wonder and celebration of life and explored the changes from the exuberant first edition of “Leaves of Grass” to the final edition when the elder statesman of American literature said goodbye with his last published words.

Brodhead captured Whitman’s wonder and celebration of life and explored the changes from the exuberant first edition of “Leaves of Grass” to the final edition when the elder statesman of American literature said goodbye with his last published words.

Whitman also matters at Duke because of the extraordinary Whitman material collected by the late Mary Duke Biddle Trent Semans with her first husband, Dr. Josiah C. Trent, and donated to Duke Libraries. Their donations are the heart of a Whitman collection that Brodhead called one of the three best in the country.

Some of the library's treasures were on view during the event, including a rare copy of the 1855 first edition, notes from Whitman in preparation for writing (including a long list of body parts and potential metaphors for them) and material from a 70th birthday party for the poet thrown by the town of Camden, NJ.

Originally writing in the days leading to the Civil War, Whitman stood apart from most other writers of the time. Whitman didn’t ignore the coming strife – Brodhead noted the numerous times that he mentions slavery and identified with “the hounded slave.” But even at the country’s darkest moment, through his poetry Whitman identified and hailed the essential radicalness of the American experiment. Two centuries later, that’s another reason why he still matters.

The full event can be watched here. The talk begins at 8:25.