'We Must Not Call It Victory': New Archives Illustrate U.S. Cold War Strategy

Former ambassador Jack Matlock has donated his extensive archives to Duke

As he headed to Switzerland in 1985 for a landmark first summit with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, President Ronald Reagan wrote a quick note that became a guiding principle for the American administration.

As he headed to Switzerland in 1985 for a landmark first summit with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, President Ronald Reagan wrote a quick note that became a guiding principle for the American administration.

It said simply: “Whatever we achieve, we must not call it victory.” This hand-scribbled lesson in nuance and ego management would help direct the American team through that and future meetings with their Soviet counterparts as the two sides sought an end to the Cold War.

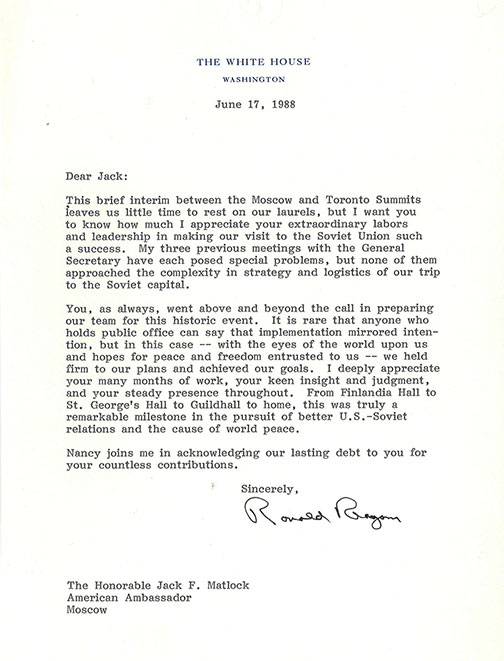

That note was later typed up and given to Jack Matlock, then a National Security Council staffer. Matlock would later become Reagan’s ambassador to the Soviet Union, playing a crucial diplomatic role as the two superpowers negotiated.

Matlock saved that note, as he did most things documenting his 35 years in foreign service.

Duke is now the beneficiary; on February 7, the university will formally open the Duke graduate’s donated archives at the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. It is a voluminous collection of letters, memos, planning documents, media reports, photographs, audio recordings and all manner of ephemera that trace the long journey of Matlock and his wife, Rebecca, including postings in Africa, Moscow and several spots in central and western Europe. The collection also includes his personal journal.

“We’re very proud to be the home of these archives,” said Edna Andrews, who directs Duke’s Center for Slavic, Eurasian and East European Studies. “They are unique. They include things scholars for decades will be using in their research. It’s wonderful.”

“We’re very proud to be the home of these archives,” said Edna Andrews, who directs Duke’s Center for Slavic, Eurasian and East European Studies. “They are unique. They include things scholars for decades will be using in their research. It’s wonderful.”

The archiving project is funded in part by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York.

The collection is massive – roughly 200 boxes of materials that library staffers at Duke are now cataloguing for use by scholars and anyone else with an interest in Cold War diplomacy and politics. Much of the material illustrates the U.S. government’s strategy during the Cold War. Letters, memos and other documents show how U.S. officials approached their Soviet counterparts seeking common ground rather than through confrontational saber-rattling, said Matlock, now 89, in a recent interview.

“The archives shed light on how we ended the Cold War,” he said. “One of the specific decisions we made when planning to negotiate with the Soviet Union was that we were not going to question their legitimacy. If it was a defeat for the Soviet Union, it wouldn’t have stuck. We didn’t win the Cold War; we negotiated an end to it.”

Matlock worked on Soviet issues in various capacities for many years before taking on the ambassadorship in 1987. He retired from foreign service in 1991 and has since held a series of academic appointments at Columbia and Princeton universities. He returned to Duke in 2015 as a Rubenstein Fellow, teaching classes on the Cold War and international leadership while beginning to sort through his massive trove of documents.

While much of the archives focuses on Matlock’s diplomatic work, it also sheds light on the life he and Rebecca led during those years.

While much of the archives focuses on Matlock’s diplomatic work, it also sheds light on the life he and Rebecca led during those years.

The couple are both members of Duke’s Class of 1950. They were introduced by a mutual friend at a meeting of a campus chapter of the United World Federalists, a group that, in the late 1940s, advocated for a world government.

Jack studied history at Duke and would later get advanced degrees in Soviet studies and Russian literature at Columbia. Rebecca majored in education and would later become a high school teacher.

The couple had five children and moved around the world as Matlock’s assignments shifted. Prior to his time in the Soviet Union, Matlock held diplomatic posts in Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia as well as seven years in Africa. As a result, he is able to speak Russian, French, German, Czech and Swahili.

In Moscow, the Matlocks often hosted cultural and social events at the ambassador’s residence – Spaso House. Rebecca was both a photographer and designer of tapestries, and exhibited her work in cities around the Soviet Union.

There are rich details about these lighter moments in the archives as well; in one memo, a staffer debates which of two American films to show a Soviet audience: “The Karate Kid” or “Splash.” It’s not clear which was chosen.

“They were ambassadors of American culture,” said Meghan Lyon, an archivist at the Rubenstein Library who is managing the processing of the collection. “This was about how Soviet people perceived America and what the Matlocks wanted people to understand about American culture and humor. So the collection shows the planning that would go into those events.”

Duke archivists are now developing a guide for members of the public interested in the collection. It will be available online to help anyone who wants to request materials. The collection’s individual documents won’t each be digitized.