Anatomy Lessons

Medical students explore the grisly, sometimes sordid world of anatomical dissection

Two months into medical school, many of the more than 500 students in the 2018 incoming classes at the Duke School of Medicine have already met their first cadavers.

Human gross anatomy is a rite of passage that usually involves a chilly lab with steel tables. Starched white lab coats. The stench of embalming chemicals. But this day’s lesson involves centuries-old books.

“We’re going to take you back in time to about 500 years ago, when people were starting to do anatomy for the first time,” said Jeffrey Baker, M.D., Ph.D., who teaches history of medicine at Duke. “As we go back in time I’m hoping you’ll come back seeing the present from a different angle.”

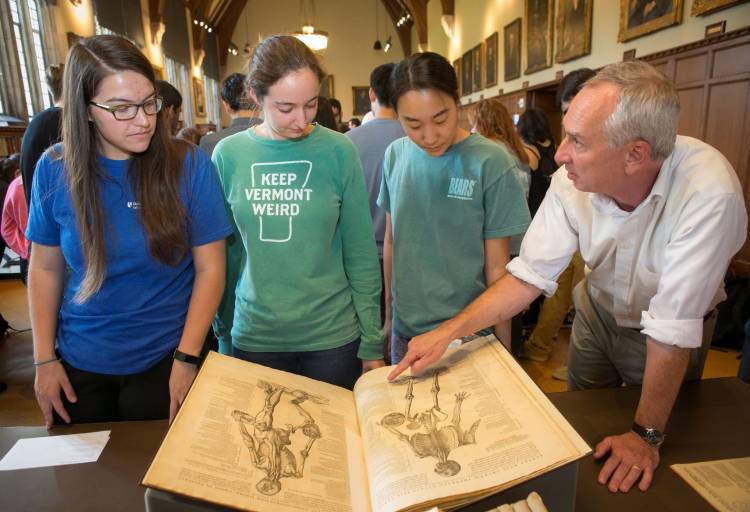

Baker and Rachel Ingold, curator of the History of Medicine Collections, usher the roughly 100 students gathered for Duke’s annual “Anatomy Day” into the Gothic Reading Room on the second floor of the Rubenstein Library.

On display are dozens of rare books from the library’s collections that illustrate how ideas about our insides have changed over time, from the works of Galen, a 2nd-century Greek physician, to Leonardo da Vinci to the modern day.

From the Gallows or the Grave

At one end of the room, a handful of students crowd around a massive leather-bound copy of “De humani corporis fabrica” (On the Fabric of the Human Body). Published in 1543 by Renaissance anatomist Andreas Vesalius, it was the first comprehensive anatomy work with illustrations based on actual dissection of human cadavers.

“It’s one of the most famous and transformative books in medicine,” said Andrew Armacost, head of collection development and curator for collections of the Rubenstein Library.

The book’s black-and-white woodcut illustrations show people in various stages of being flayed. Armacost turns the 700-some pages to an image of the skinless corpse of a man standing, lifelike, amid the Italian countryside, his flesh stripped away until little remains but his skeleton.

Most of the cadavers dissected by medical students today are voluntarily donated by the person or their loved ones, Baker said. But for centuries, anatomists like Vesalius often procured their bodies through more questionable means.

From the Middle Ages, medical schools in Europe relied on the corpses of hanged criminals brought fresh from the gallows. A chronic shortage of bodies meant that grave robbery was also rampant.

“They tended to come from the paupers’ area of the graveyard,” Baker said.

Medical murders?

On the other side of the room, Ingold shows a group of students a life-sized illustration of a woman’s dissected pregnant torso cut down to the uterus.

Apparently the woman died in her ninth month of pregnancy. Now headless, her legs have been reduced to stumps cut off mid-thigh, like a dinner ham.

"It's incredibly beautiful and incredibly disturbing at the same time," Ingold said.

It comes from Scottish physician William Hunter's 1774 "Anatomy of the Human Pregnant Uterus Exhibited in Figures.” The collection of 34 copperplate engravings offered one of the first detailed glimpses of the stages of pregnancy and the inner workings of the womb, long before fetal ultrasound and MRI.

Hunter didn’t disclose the source of the dozen or so bodies that appeared in his atlas, but given the chances of opening a grave to find a full-term pregnant corpse, some scholars suspect the women were murdered to order.

In an effort to stop body snatching and medical murders, Britain’s Anatomy Act of 1832 made it permissible for anatomy schools to use unclaimed bodies from hospitals or poorhouses. “But dubious ethics continued nonetheless,” Baker said.

In an effort to stop body snatching and medical murders, Britain’s Anatomy Act of 1832 made it permissible for anatomy schools to use unclaimed bodies from hospitals or poorhouses. “But dubious ethics continued nonetheless,” Baker said.

One of the most infamous 20th-century examples sits just a few feet away, where a copy of University of Vienna anatomist Eduard Pernkopf’s “Topographical Anatomy of Man” lies open to a detailed painting of a gaunt man whose skin is peeled back to reveal the underlying muscles, nerves and fascia of his head and neck.

First published in Berlin in 1943, Pernkopf’s multi-volume book was widely used and admired as a masterpiece until 20 years ago, when researchers determined -- based on several early edition illustrations signed with small swastikas or “SS” signs -- that Pernkopf was a Nazi who had used the bodies of concentration camp victims as models.

Laura Micham, director of the Sallie Bingham Center for Women's History and Culture, points to a stamped card tucked into a pocket on the back cover showing that Duke students checked it out of the library on a semi-regular basis until the late 1980s.

“Finally in the 1990s the University of Vienna responded to mounting pressure to investigate the origins of the bodies used in Pernkopf’s atlas, and the publisher stopped printing new copies,” Micham said.

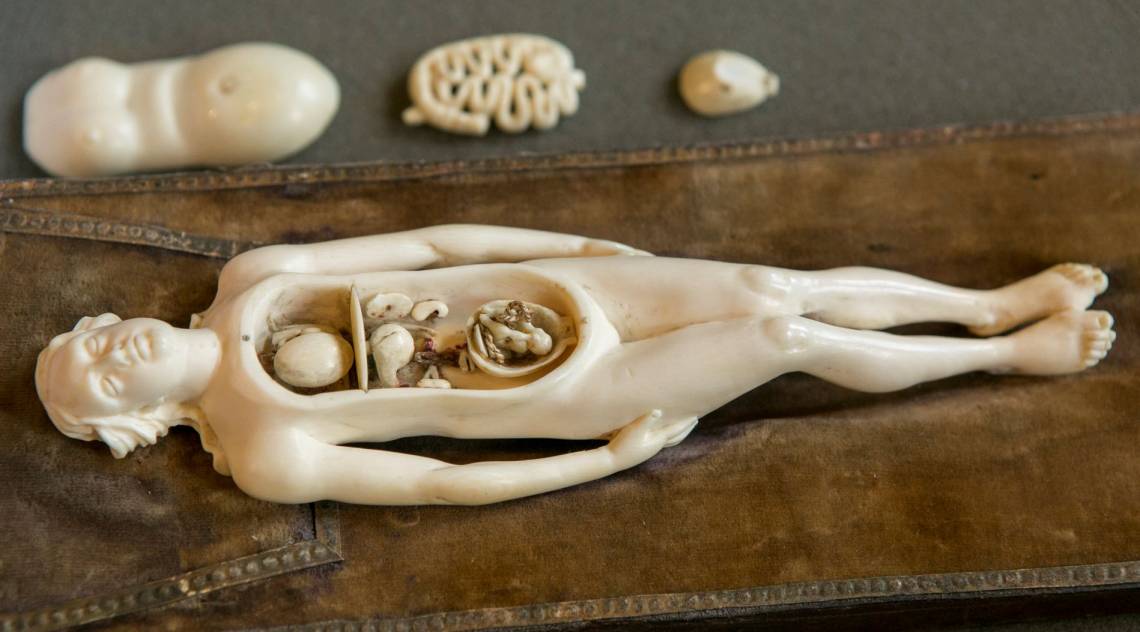

Not every artifact is grisly. At another table, students pore over the only known copies of four 17th-century copperplate engravings, none of them signed or dated, showing naked human figures in different stages of life surrounded by birds, trees, celestial maps and palm reading charts.

The people are depicted carrying flasks of urine, phlegm, blood or bile -- a reference to the then-widespread notion that the key to health was a balanced mix of bodily fluids.

Taylor De Klerk, Josiah Charles Trent History of Medicine intern, lifts layer upon layer of paper flaps to reveal the secrets within their bodies, leaving their innards poking out from the page like an anatomical pop-up book.

Nearby, two students gingerly turn the hand-painted pages of a 19th century Japanese picture book showing how to treat various maladies, from swelling to fractures.

Eventually the students trickle out and head home, exhausted from cramming for a morning exam.

“Science doesn't rob you of your humanity,” Baker said. “But the act of dissecting another human, without reflecting on that person's story and background, can lead you to see people as mere bodies. This is a time for that kind of reflection.”