Oh, the Places You Could Go - with a Ph.D.

How graduate education is changing to prepare students for broader career options

The pace of work for doctoral students is more tortoise than hare, which is why a recent assignment pushed Lizzie Hunsaker far from her comfort zone.

She was asked to summarize a journal article in jargon-free writing suitable for a mainstream media outlet. In 20 minutes.

Ack!

“What I liked was that we had little to no prep time, and we just had to do it,” recalled Hunsaker, a chemistry Ph.D. student. “It was challenging but highly effective. Someone can give a lecture on how to communicate your science, or they can make you do it.”

The class wasn’t required as part of Hunsaker’s doctoral training. It was a science communications course offered as part of the new Duke Summer Doctoral Academy, offered to Ph.D. students earlier this year to fill in gaps in their traditional graduate training.

The new, voluntary venture is one of many resources around the university that help graduate students prepare for careers in academia or, increasingly, outside of it.

Though the job prospects for newly minted Ph.D.’s in many fields are growing more scarce, that isn’t the impetus for many of the initiatives underway, officials say.

Rather, there’s a broad desire at Duke to make doctoral students as skilled as possible, regardless of where their careers take them, said Ed Balleisen, a Duke historian. Balleisen is both co-chair of a campus task force examining doctoral education and a leader of the Versatile Humanists project, the latter a grant-funded effort to prepare humanities graduate students for life after Duke.

“We want to train people to make a difference wherever they go,” Balleisen said. “It’s the capacity to work with others in different fields. It’s the ability to pose questions with broader salience. It’s communicating effectively within a field and outside it, whether with other academics, to decision-makers, or to the broader public.”

Doctoral Academy

Hunsaker and roughly 200 other graduate students took part in the first summer doctoral academy earlier this year. There were 16 classes that met three hours a day for five days. The topics ranged widely -- from visual storytelling to negotiation tactics to the best ways to use archival materials in undergraduate teaching.

“It wasn’t going to go on for 10 or 14 weeks. People wanted to be in those classrooms and no one felt burdened by it,” said Executive Vice Provost Jennifer Francis, an organizer of the initiative. “Students weren’t coming with prior knowledge and experience, but they had enthusiasm.”

In Aria Chernik’s class, the enthusiasm was palpable. A lecturing fellow at Duke’s Social Science Research Institute, Chernik co-taught an education technology class with Matthew Rascoff, Duke’s associate vice provost for digital education and innovation.

Their class, which enrolled doctoral students from disciplines as disparate as microbiology, religion, literature and engineering, included a ‘design sprint.’ In it, teams of students sought out a problem in education, devised a technology-based product to solve it and then actually designed that product. Again, the hare approach, not the tortoise.

“It was wonderful to see the awe in learning,” Chernik reflected. “All of these students are getting their Ph.D.’s and have been in school an extremely long time. On the first day, when we told them what they’d be doing on the last day, they looked at us like ‘there’s no way!’ It was outside their comfort zones.”

In the Graduate School, a change in thinking

At Duke’s Graduate School, assistant dean Melissa Bostrom and others are trying to change a mindset.

Too many master’s and doctoral students view a shift away from the academic path as failure – even if, after a couple years in graduate school, it becomes clear academia isn’t for them. But it shouldn’t be that way, Bostrom argues, particularly because academic jobs are scarce in many disciplines in the humanities and elsewhere.

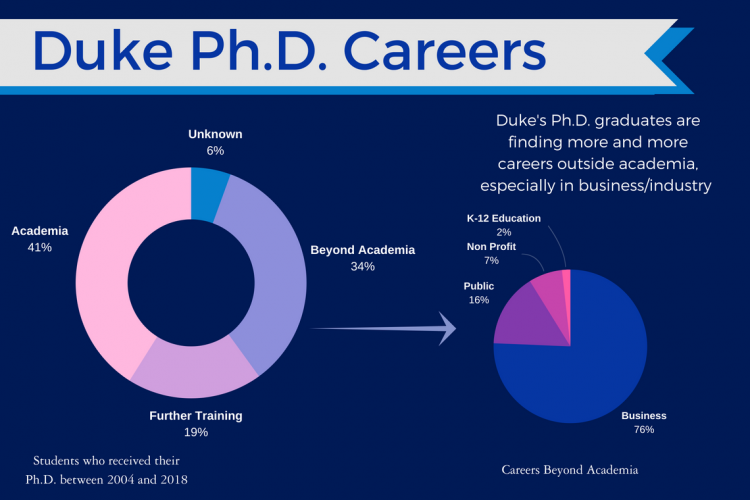

The data isn’t new, but it’s still jarring. The majority of Ph.D. graduates from Duke end up in business and industry, a fact influenced by industry demands for skilled graduates in engineering and the physical sciences, said Bostrom, the graduate school’s assistant dean for graduate student professional development.

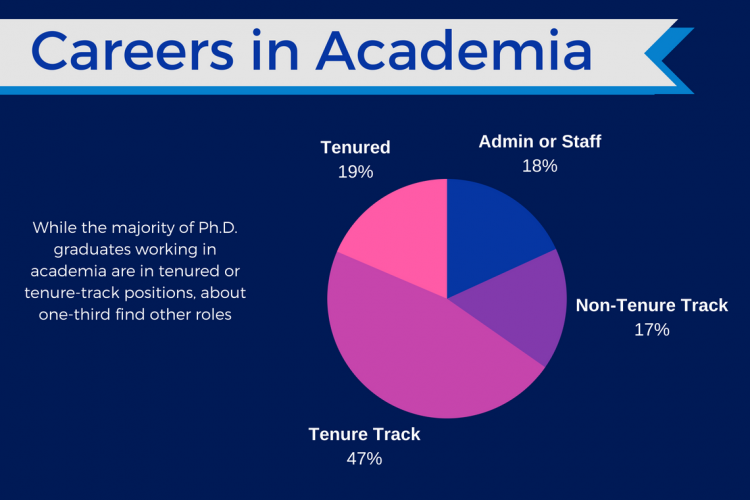

The story is different in other disciplines. While most humanities Ph.D. graduates pursue tenure-track faculty positions, only about half nationally actually get those jobs, a reflection of a very tight job market. (There is, though, fluctuation within the humanities, and some Duke departments and programs report higher numbers of grads in tenure-track positions.)

It’s even more stark in biology and biomedical sciences, Bostrom said; in biology, for example, just about 10 percent of students who enter Ph.D. programs nationwide will end up in tenure-track academic jobs. That number rises to 15 percent among Duke Ph.D. graduates in the biological and biomedical sciences, with almost twice that many going into business and industry.

“There is a tremendous mismatch between the number of graduate students and postdocs and the number of tenure-track jobs available,” she said.

Yet, many students still see that as the primary career path, often stalling out in relatively low-paying, tenuous postdoc positions for years.

“Changing that mindset is critical,” Bostrom said. “Academic culture is very much about the CV, about accomplishments and achievements. I try to get students to focus on the skills they have that make them successful.”

That conversation is often eye-opening for students who can be unaware of just how many coveted skills they possess.

“The ability to fail and fail and fail some more and then keep going and try again and make discoveries – those are really valuable skills.”

-- Melissa Bostrom, Graduate School assistant dean for graduate student professional development

“What are the skills that go into being a good TA? Planning. Time management. Conflict resolution. Problem solving. Communication, leadership,” Bostrom said. “Those are all skills our students use in a classroom setting, but we don’t talk about them in Ph.D. programs.”

“The ability to fail and fail and fail some more and then keep going and try again and make discoveries – those are really valuable skills,” she added.

The Graduate School has a battery of resources to help students think broadly about their skills and future. They include the Duke OPTIONS website, which lets students create a personalized career planning roadmap based on their specifics and interests. And if their goals and interests change, they can go back and make changes to their timeline.

Employers also stress the importance of writing and communication skills, the impetus for a professional development blog the school hosts and students contribute to. It is filled with profiles of successful Duke alumni, written by current Duke graduate students.

Making the University Smaller

Like the doctoral academy, Duke’s Versatile Humanists initiative attempts to shift long-held mindsets among graduate students that they must study within an academic department, an oft-solitary and, some say, outmoded approach to graduate education.

“The premise we’ve had for decades is that graduate students predominantly get their mentoring and advice through departmental channels,” said Balleisen. “That structure doesn’t often provide students a full appreciation for what’s available across the university.”

So Versatile Humanists purposefully makes the full university far smaller and more attainable -- customizing the advising process, creating mentoring networks, building collaborative research teams and providing internship opportunities in environments that students might not otherwise experience.

Take Ashley Rose Young, for example.

Back in 2017, Young was close to finishing her dissertation and heading onto the academic job market – the traditional path for history Ph.D.’s – when the detour she had hoped for finally emerged.

“One of the things I like about my job is that I can go from conducting archival research, to recording a podcast, to hosting a cooking demo related to Julia Child and her cooking legacy. These are all about food, but they’re distinct. I like that diversity.”

-- Ashley Rose Young

It came in the form of a two-month internship at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History – funded by Duke – that quickly turned into a job offer. Now, Young is happily ensconced in her new career as a food historian at the Smithsonian. It is a multi-faceted job of her dreams, mixing traditional scholarship – like poring over archival material and collecting oral histories – with more public work like bringing in celebrity chefs for cooking demonstrations and curating an exhibition that features Julia Child’s Cambridge, Massachusetts kitchen.

The internship came in Young’s seventh and final year as a doctoral student, and the opportunity was unusual in that internships are generally associated with undergrads looking for summer work experience.

But Duke officials see these graduate internships as a critical cog in the new Versatile Humanists initiative, Balleisen said. In its first year, the program connected seven students with internships, and nine more this summer.

“We need more exposure for doctoral students to collaborative environments,” he said. “That’s a crucial dimension of the world of work outside academia, and increasingly so, inside academia.”

For Young, it provided an edge she desperately needed.

“Versatile Humanists was so key for me,” Young said recently. “It’s hard for institutions to pay interns to do labor, so for Duke to sponsor me was a huge deal. I’m not sure I would have made the internship happen otherwise. It provided funding, structure and legitimacy.”

Young first got the museum bug while a Yale undergraduate interning at the Southern Food and Beverage Museum in New Orleans. When she entered the history Ph.D. program at Duke, she planned to go in two directions at once – doing work that would ready her for both an academic career and one now known as ‘alt-academic’ (graduate student shorthand for careers held by Ph.D.’s that aren’t tenure-track academic appointments).

Now she has what she considers a best-of-both-worlds career that involves serious scholarship and a lot of interaction with the public.

“One of the things I like about my job is that I can go from conducting archival research, to recording a podcast, to hosting a cooking demo related to Julia Child and her cooking legacy,” she said. “These are all about food, but they’re distinct. I like that diversity. I like that I can be a serious researcher and two hours later I can be chatting with kids about technological changes in the microwave.”