When the Great War Came to Durham

Duke History student curates WWI exhibit at Durham Museum of History

On Aug. 17, the Museum of Durham History will premiere “Durham During the Great War,” an exhibit that celebrates the contributions of Durham’s citizens at home and abroad during World War I. The exhibit coincides with the upcoming centennial anniversary of the Armistice on Nov. 11.

On Aug. 17, the Museum of Durham History will premiere “Durham During the Great War,” an exhibit that celebrates the contributions of Durham’s citizens at home and abroad during World War I. The exhibit coincides with the upcoming centennial anniversary of the Armistice on Nov. 11.

I have had the privilege of co-curating this exhibit alongside Jeanette Shaffer, director of operations at the museum. Jeanette and I spent most of our summer researching stories of men who heeded the call and fought bravely for their country; stories of women, black and white, who labored tirelessly in tobacco factories and textile mills, joined conservation efforts, and trained to become nurses and stenographers; stories of success in the tobacco industry as Durham cigarettes gained heightened popularity with soldiers abroad; and stories of segregation and violence as African American men who fought for freedom on the war front returned to a Durham still steeped in racial animosity.

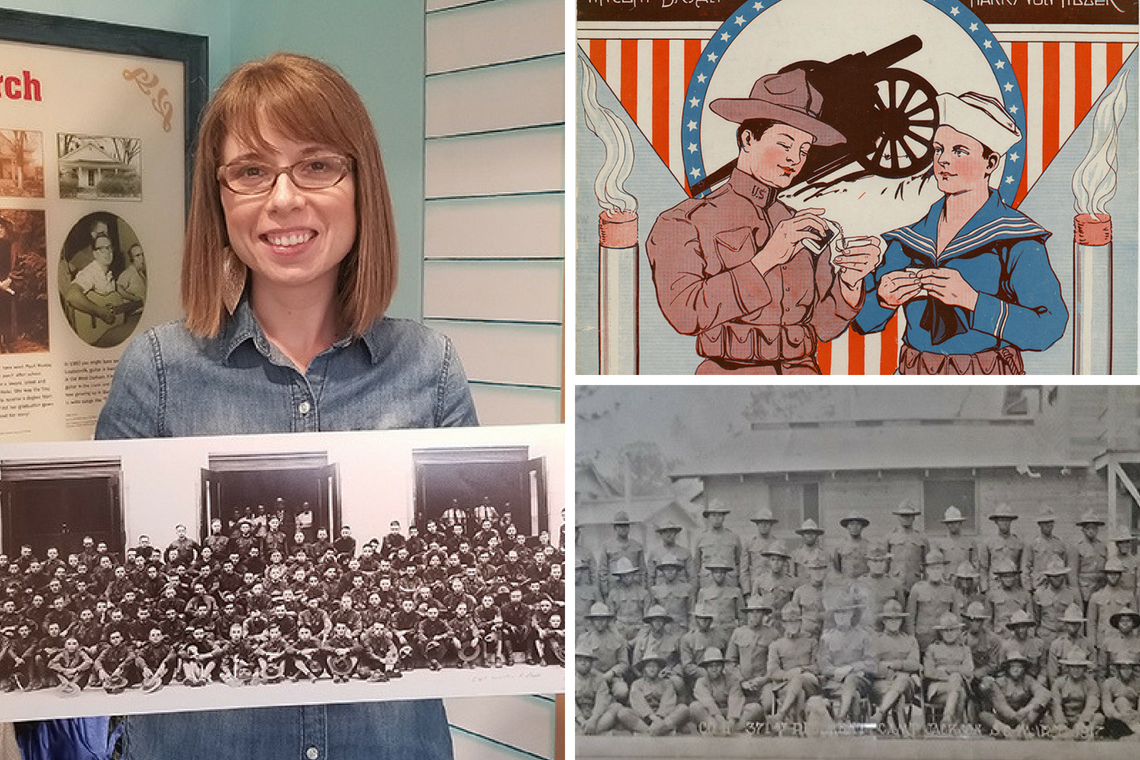

These stories are featured prominently in the exhibit and told through photographs, newspaper clippings, posters, and oral histories that we have gathered over the past few months.

In the process of preparing the exhibit we came across several lifelong Durhamites, each of whom had pieced together their family’s World War I legacies through stories passed down to them, their own research and, in one case, by traveling to France to trace the steps of their relative. These three friends have known each other for most of their lives: James “Jim” Pulley, Thomas Hunt, and Russell Barringer. I sat down with all of them in the Museum’s Story Room earlier this summer to talk about the war and to record their oral histories, which will be featured in the exhibit.

Jim’s father, Wallace R. Pulley, was a member of Company “M,” an all-white military unit from Durham. Jim reminisced about when his dad and the other members of Company “M” left Durham, taking a photograph in front of the old courthouse before boarding the train. Jim’s mother fainted as the train pulled away from the station. Jim’s other favorite memory about his dad’s war days entails his father’s helmet, which is currently on display at the American Legion in Durham where Jim volunteers regularly and where we had our initial meeting.

Jim let me photograph the helmet, which has several shrapnel holes. Jim loves telling the story about how his father’s helmet was hit while he was putting on his gas mask in the trenches in France. Lucky for Pulley, he was only holding the helmet at the time and suffered no injuries.

Thomas Hunt’s father, Clarence Marvin Hunt Sr. was a corporal in Battery “C”, which had a number of prominent citizens from Durham including Wyatt Dixon. His father did not talk about the war very often, inspiring him to do his own digging later in life. Thomas has spent a great deal of time reading through Wyatt Dixon’s journal, a portion of which is featured in the exhibit. He found his dad’s name in the journal along with some interesting anecdotes about their time in training at Camp Sevier in South Carolina. Hunt, Dixon, and the other men had to train with wooden guns rather than actual weaponry because of shortages. They were later sent to France.

Russell Barringer’s father-in-law, Hubert Teer, was an officer in the 371st Infantry Regiment, Company “L,” which was made up of African American enlisted men and white officers from North Carolina and other neighboring states. African American troops could not fight alongside white troops, so many were given non-combat jobs instead. Finding the policy unfair, Teer and his fellow officers petitioned the war department on grounds that black troops deserved to be able to fight for their country. The war department eventually approved the request, but only allowed the men to fight with French divisions and not with their American counterparts.

Russell and his wife Mary later went to France in honor of her father. While staring at a World War I monument they noticed something rather curious—the name of one soldier, Freddie Stowers, etched in gold. As they were leaving, Mary turned around and serendipitously spotted the name again on a grave marker. He was killed while leading an offensive attack in France in 1918 and was given the Medal of Honor posthumously in 1991. When the Barringers returned to the states, they located the Stowers family in South Carolina and went to visit them to find out more about Stowers’ life and to tell them about Hubert Teer.

Jim, Thomas, and Russell all have very unusual stories to share about their family members’ involvement in the Great War, but all three have one important commonality—their love of Durham’s heritage and their dedication to sharing their history whenever possible. We have used their stories and others to tell the history of World War I in Durham from the vantage point of the entire community, engaging the past in a way we hope will foster curiosity and allow everyone to see the war through diverse perspectives.