Speaking the Language of Care

Medical interpreters at Duke Health play a vital role

When Rene Chavez and his Duke Health doctors gathered for one final meeting prior to his hand transplant surgery, there was plenty to discuss. Forms had to be signed, lingering worries had to be eased and, with fewer than 25 hand transplants performed in the country at that point – and none in North Carolina – communication was crucial.

Before the meeting ended, Chavez, who lost his left hand in a childhood accident, led a prayer.

“He was praying for the Lord to bless the hands that were going to touch him,” said Maria De La Cruz Bunce, a Duke Health medical interpreter. “It was a very beautiful moment.”

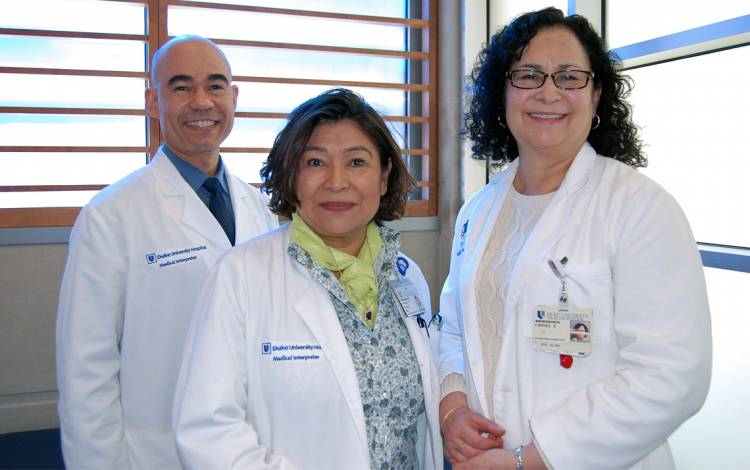

Chavez, a 54-year old grandfather from Texas, speaks Spanish as his first language. As one of roughly 25 full-time medical interpreters in Duke Health’s International Patient Services Department, Bunce played a significant role, ensuring communication between Chavez and his caregivers flowed freely.

Chavez, a 54-year old grandfather from Texas, speaks Spanish as his first language. As one of roughly 25 full-time medical interpreters in Duke Health’s International Patient Services Department, Bunce played a significant role, ensuring communication between Chavez and his caregivers flowed freely.

“Interpreters make possible the communication between the medical team, the patients, their families and friends,” said Linda Carime Cendales, an associate professor of surgery at the Duke University School of Medicine who led the transplant team.

“I’m always impressed with their knowledge, their command of their languages, their understanding of the context, and most importantly, their compassion.”

Serving a diverse community, and with high-level care that attracts patients from around the globe, Duke medical interpreters field around 200 requests per day. There are around 20 Spanish interpreters on staff, as well as others who speak Arabic, French and American Sign Language. Interpreters for other languages can be arranged by phone, by video or in-person through an agency.

Interpreters undergo training on medical terminology and how to be a calming influence for patients while not altering interactions with doctors.

“Our job goes from simple questions, like ‘What is this appointment for?’ to conferences where you’re dealing with life and death issues,” said Medical Interpreter Flora Weisleder.

Nouria Belmouloud, program coordinator for International Patient Services, said interpreters give non-English-speaking patients the same relationships with their doctors as an English speaker. That means they must not filter dialogue.

“We tell patients, ‘I’m your voice. Whatever you want to say, I will say,’” said Grisel Diaz, a medical interpreter.

Diaz and the other interpreters must also be ready for anything. Medical Interpreter Joel Pena discovered that in 2016.

Two weeks after Rene Chavez’ successful transplant, a news conference was held featuring members of the hand transplant team and Chavez. Pena was chosen as the interpreter for Chavez.

“The press conference was something new for me,” Pena said.

Fielding media questions and translating answers from Chavez, Pena showed the outside world how language barriers are never insurmountable for Duke patients.