To Achieve Food Security for All, Build Trust With Communities

Former UN World Food Programme director speaks at Duke's new World Food Policy Center

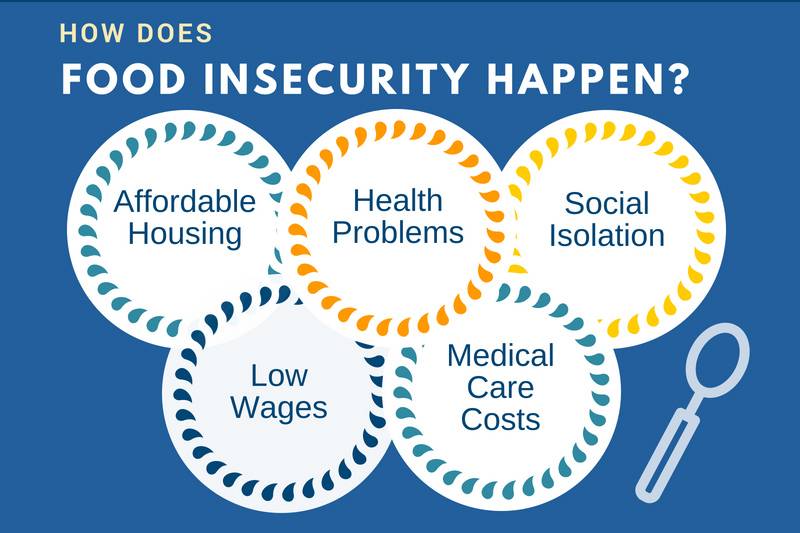

Across the globe, there is more obesity, racial inequity in food access, malnutrition, diet-related disease and food waste than ever before. Those issues interconnect with poverty and inequality as a driver of food insecurity.

Across the globe, there is more obesity, racial inequity in food access, malnutrition, diet-related disease and food waste than ever before. Those issues interconnect with poverty and inequality as a driver of food insecurity.

To meet the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal of zero hunger in the world, nations must succeed at providing universal food security, according to Ertharin Cousin, former UN Director of the World Food Programme and U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Agencies for Food and Agriculture.

“To achieve food security, we need to enable access—the affordability of nutritious food,” Cousin said. “We need to ensure availability of nutritious food. And we need to ensure safe consumption. The food and water we consume must be safe.”

Social science and agricultural technology academics, industry members and community leaders engaged in conversation on food security challenges and opportunities last week in Research Triangle Park. Duke’s World Food Policy Center (WFPC) organized the program, held at the NC Biotechnology Center and sponsored by Syngenta.

"Our food system must be sustainable. That means it must embrace the entire agricultural value chain and address economic, social and environmental needs," Cousin said. "We too often refer to our global food system as sustainable—but it's not. It is just productive, but that is not enough.

“We need cultural changes for innovations to be adopted by growers around the world. We need R&D technology to be available worldwide – not just the Global North (use this contextual link for people who need the definition of Global North and Global South. Our inability to provide technology for smallholder farmers (use this contextual link to define smallholder farmers in the Global South will not allow us to provide the production needed to feed the growing population,” she said.

According to the Committee on World Food Security the majority of the 570 million farms in the world are small. Smallholders supply 80 percent of overall food produced in Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America through farmers, artisan fisherfolk, pastoralists, landless and indigenous people. Also, 70 percent of the 1.4 billion impoverished people live in rural areas, and 75 percent of these rural poor are also smallholders.

“When we think about what is sustainable, and what it will take to create a sustainable food system, we know that it is about the people. That what we create must be safe for the people, must not detrimentally impact our environment, and that it does make a profit. But no one of those elements can be allowed to outweigh the other two pillars. What we do must be supportive of human and planetary health,” she said.

Cousin discussed her efforts to address food deserts while she worked in industry and her international work with the U.N. World Food Programme during the Obama Administration. Food desertsare defined as parts of the country, usually impoverished areas, where access to fresh fruit, vegetables and other healthful whole foods is lacking.

“No one entity can perform the work of food security alone,” Cousin said. “It requires partnerships between the private sector and academics, farmers and growers and consumers, between government and industry and communities. We need to have mayors and government leaders at all levels across our country working together with communities and community leaders. Trust, collaboration and relationships are what is needed to make the policies changes needed to help us address food security. And we must also have imagination, science and technology.”

All heads nodded in the room when the need to build and sustain relationships and trust came up, repeatedly.

“We have an opportunity to build a narrative about science and technology that can be embraced and understood by the global public – and we not only have an opportunity, we have a requirement to ensure that we build that narrative,” Cousin said. “And we must communicate it in a way that those who don't work in the science and tech every day can understand and embrace it as part of their desire to provide for themselves and their children with nutritious food. Research-driven partnerships, regulatory partnerships, and imagination – these are the things we need.”

Cousin described genetically modified foods as an example of a where science failed to build trust with the public.

“The U.S. leads in imagination. We always have, we always should if we do not become afraid of the science that we create. Our challenge is to make imagination less scary. Making ‘different' embraceable and acceptable. Making it personal. For that mother who needs to feed her children and is looking for the solutions that she can afford and know it is also safe. Which means that partnership [with the public] must be built on trust.

“As we build this platform to support the research, innovation, the policies and the imagination, we must build it on trust in conversations where we come together as neighbors and community leaders. We must talk about not just what the challenges are but also the opportunities to ensure that every child universally has access to healthy and nutritious food,” she said.