On the night of April 4, 1968, William Turner was coming back from a physics exam when he learned that Martin Luther King Jr. had been shot and killed on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee.

On the night of April 4, 1968, William Turner was coming back from a physics exam when he learned that Martin Luther King Jr. had been shot and killed on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee.

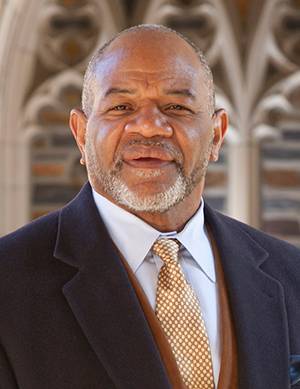

Turner now teaches in the Duke Divinity School, where he is James T. and Alice Mead Cleland Professor of the Practice of Preaching. But in April 1968 he was among a handful of African-American students at Duke, which accepted its first black undergraduates in 1963.

He walked into his dorm, where the lobby television was switched on, and stood and watched in silence as images of rioting crowds in city after city washed across the TV screen.

“That night is a blur except that I watched the news over and over, and saw the eruptions begging to develop all over the country,” Turner said. “And of course Durham was caught in it, too. And so the question on campus was, ‘How shall we respond’?”

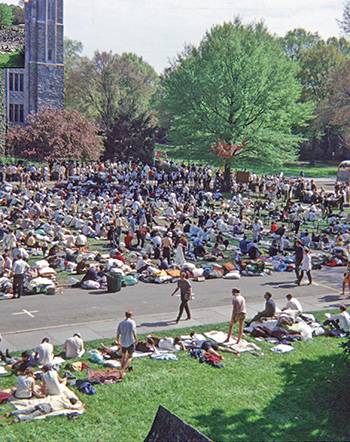

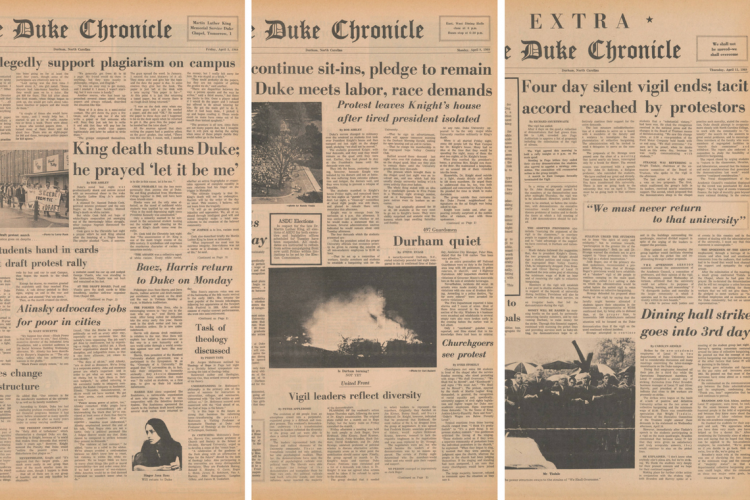

The answer came quickly. In response to King’s assassination, students camped for days in front of Duke Chapel seeking better treatment for African-Americans at Duke in what became known as the Silent Vigil.

Those events are on Turner’s mind as he contemplates King’s death 50 years ago and prepares to step into the pulpit and preach to members of the Class of 1968 during reunion weekend on April 15.

Turner has an unusual perspective on how King’s death resonated at Duke -- and on how that response helped put Duke on a different course. He has spent a half-century on campus as an undergraduate, a Ph.D. student, a staff member and early leader of the black studies program, and finally as a Divinity School professor.

Turner, who is also pastor at Mt. Level Baptist Church in Durham, retires from Duke in May, and his retirement will be marked with an April 9 program at Goodson Chapel. During his 50 years on campus, he witnessed Duke’s evolution from a Southern university with a smattering of black students into a national university with one of the country’s most highly ranked departments of African and African American Studies.

He sees the Silent Vigil following King’s death as a critical pivot point in Duke’s evolution.

“The Vigil was the first campus-wide event that took up the issues of black students and their needs and those of the non-academic employees,” Turner said. “It answered the question of whether Duke students were essentially members of a silent generation.

“It thrust Duke into the headlines and the limelight with the larger momentous events of our time.”

Turner grew up in segregated Virginia, in a tight-knit African American community where he attended all-black schools. His grandfather had once lived in Durham, helping to build Duke Hospital. But he arrived at Duke by happenstance, after a math teacher handed him an application and urged him to apply.

Turner grew up in segregated Virginia, in a tight-knit African American community where he attended all-black schools. His grandfather had once lived in Durham, helping to build Duke Hospital. But he arrived at Duke by happenstance, after a math teacher handed him an application and urged him to apply.

When Turner headed off to Duke, his father had this advice: “Son, find your people.”

Turner found community, partly among the few other African-American students at Duke. He also befriended staff members, including the African-American housekeeper who tended his building. She invited him to her church and Turner accepted, going to church with her regularly on Sundays during his time at Duke.

He also helped integrate the Duke football team, joining as a walk-on and becoming one of the team’s first two black players. It was one new experience among many.

“This was a brand-new experience, a social experiment,” Turner said. “We really didn’t know what to expect. We took it in stride.”

“You have a Southern way of life, a Southern orthodoxy…where everybody has their place, where everything is tiered. Now the question would be whether or not people come here to learn how to do that more perfectly – to perpetuate this Southern orthodoxy and tiered society. Or is this a place where people can come and participate in the opening of society?” - William Turner

The university Turner entered was oriented toward the Southern gentry, he says. Many of Turner’s classmates were from wealthy families. He remembers his surprise upon returning to his dorm room and finding clean sheets on his bed and pajamas folded and neatly tucked beneath his pillow.

But in the late 1960s, Duke was changing. Turner injured his knee during a football practice and checked into Duke Hospital. As his father and grandfather sat by his bedside, a trio of white students – two men and a woman -- stopped by to check up on him. Turner says his grandfather looked shaken.

“‘He’s just not ready for that,’” Turner’s father explained. Turner’s great-grandfather had been lynched in Person County for consorting with a white woman, his father told Turner.

“Social mixing was not a thing to be done in the pre-Civil Rights South,” Turner said. “You just didn’t do that on pain of losing your life. Social mixing – that was something we never did until we came here, for me and for most of us.”

Social mixing was beginning, but Duke was hardly a radical place. In March 1968, Duke professor Jack Preiss was quoted in Sports Illustrated referring to Duke students as part of the “Timid Generation.” Then came King’s death.

For many at Duke, the assassination was a moment of reckoning. As the news spread, more and more students gathered in front of Duke Chapel. Turner hesitated at first, then joined the crowd as it swelled to more than 1,400. The students camped for days demanding more attention to African-American issues, including better pay for Duke’s hourly employees.

Duke’s lone black professor at the time, Samuel DuBois Cook, was a college classmate of King. He returned from King’s funeral and addressed the crowd that fanned out in front of the Chapel.

Student activism continued over the following months, including calls for the establishment of a Black Studies Program. That demand was high on the list a year later when Turner joined other students in taking over the Allen Building in 1969. The Faculty Council approved the new program in May 1969, establishing the precursor for what is now Duke’s highly ranked Department of African and African-American Studies.

In Turner’s view, these critical inflection points helped determine what direction the university would take.

“You get this series of events that go together like hand in glove in 1968 and 1969,” Turner said. “And then after 1969 you really begin to see the change in character of the university.”

“You have a Southern way of life, a Southern orthodoxy…where everybody has their place, where everything is tiered. Now the question would be whether or not people come here to learn how to do that more perfectly – to perpetuate this Southern orthodoxy and tiered society. Or is this a place where people can come and participate in the opening of society?”

By 1974, some answers were emerging. Turner, who had taken part in the Vigil and the Allen Building takeover, had an office in the Allen Building as assistant provost and dean of Black Affairs.

By 1974, some answers were emerging. Turner, who had taken part in the Vigil and the Allen Building takeover, had an office in the Allen Building as assistant provost and dean of Black Affairs.

Duke’s conversation about race – a conversation that is still far from over – had taken an important turn, he said.

“I would say that our time at Duke forced the issue of whether Duke would be another good regional institution or whether it would be a world-class university,” Turner said. “Our presence forced the issue.”

Turner is still tweaking his sermon for reunion weekend. For his message to the Class of 1968, he’s considering a passage from 1 John 3: “Beloved, now we are the children of God. But it does not yet appear what we shall be.”

The message seems appropriate as Turner and others gather to reflect on events of 50 years ago, and all the ways the Spring of 1968 still echoes today.

“Surely, we didn’t have any idea of what we were doing in those days,” Turner said.

“We really have no clue about how the path of our life will unfold.”

More on MLK

- Richard Lischer: "What Martin Luther King Jr. Would Think of Black Lives Matter Today?" Washington Post.

- Darrell Miller: "Guard These True Monuments to Martin Luther King Jr." Newsday.

- Bob Ashley: “From Goldwater Republican to McGovern Democrat, transformed by Vigil.” Duke Chronicle

- Harry Boyte: “Duke Vigil reunion: A tribute to Oliver Harvey.” Duke Chronicle