Putting SNCC Veterans Into the Civil Rights Era Spotlight

Exhibit and conference reflects on how young activists helped launch a movement

In the aftermath of the 1960 Greensboro sit-ins, young African-American activists weren’t interested in sitting on their laurels. Within a few years, the multi-racial Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, popularly known as SNCC, was active throughout the South and in part of the Northeast, putting their lives at risk to register voters, teach children, reform political institutions and create local grassroots organizations that were central to the civil rights movement.

“SNCC veterans are aware the light never shined on their work as it did on the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and other senior statesmen of the civil rights movement,” said John Gartrell, director of the John Hope Franklin Research Center in Duke’s Rubenstein Library. “They were young activists who left their studies to work with local people out of the spotlight: sharecroppers, maids. But it was that work at the local level that was so important to the movement.”

Five decades later, Duke University is partnering with SNCC veterans to ensure their stories can inspire a new generation of activists. Central to that effort is the SNCC Digital Gateway, created in collaboration with the Duke University Library, Center for Documentary Studies and the SNCC Legacy Project, the project is comprised of digitized SNCC archives from around the country, including materials from the John Hope Franklin Research Center and the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture in the Rubenstein Library.

Materials from the collection are featured this month in an exhibit at the entrance of the Duke University Library. The exhibit will culminate with a two-day conference on the civil rights movement involving scholars, SNCC veterans and contemporary young activists.

How SNCC Became SNCC

The way SNCC became SNCC is both ordinary and extraordinary. The audio recording with former SNCC field secretary, Charlie Cobb, pictured right, reflects on the beginnings that shaped the organization.

The starting point is the sit-in protests against segregation and white supremacy that initially brought together the student activists who would form SNCC. Although these sit-ins that first erupted in Greensboro, North Carolina, on Feb. 1, 1960, were spontaneous and spread rapidly across the South, they quickly became the foundation for a major organization because of one of the most significant figures of 20th century social change, Ella Baker.

Baker, the executive secretary of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, helped the students organize the initial SNCC conference in 1960 on the Shaw University campus in Raleigh.

Attracting Recruits

Judy Richardson was raised in Tarrytown, New York. Her father was a labor leader who died on the assembly line when she was 7. As a Swarthmore student, she came south to protest segregation on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in 1962 when she learned about SNCC. She quickly decided to take a semester off from Swarthmore.

Judy Richardson was raised in Tarrytown, New York. Her father was a labor leader who died on the assembly line when she was 7. As a Swarthmore student, she came south to protest segregation on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in 1962 when she learned about SNCC. She quickly decided to take a semester off from Swarthmore.

Note that on her job application she told the organization to never contact her mother: Richardson and many other SNCC activists were conscious of the risks they were taking and looked to protect their families from concern.

Her story also underscores the role women played in the movement and challenges they faced. Although Richardson appreciated her role in SNCC, she grew tired of taking the minutes at organizational meetings, and she noticed that only women were doing the minutes. So, in the spring of 1964, she and the four other women in the Atlanta office decided to stage a sit-in.

Mentors

SNCC veteran Cortland Cox talks about the role of Ella Baker and the creation of local networks.

While the young students were conscious of needing to take a different path than their senior activists, they eagerly learned from experienced mentors. There would not have been a SNCC without Ella Baker. While serving as executive secretary for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Baker immediately recognized the potential of the students involved in the sit-in movement and wanted to bring leaders of the movement together to meet one another and to consider future work.

The young SNCC activists had a complicated relationship to the older civil rights organizations such as the NAACP, the Council on Racial Equality (CORE), and King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), but their coordination and cooperation with Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer and others underscores how the different organizations supported each other.

Freedom Summer, Mississippi 1964

Freedom Summer, Mississippi 1964

Robert Moses was one of many SNCC activists who doubled as staff workers for the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), which organized the Freedom Summer in Mississippi. For 10 hot weeks, a multi-racial coalition of activists came to Mississippi focused on several goals: To establish Freedom Schools and community centers throughout the state, to increase black voter registration, and to ultimately challenge the all-white delegation that would represent the state at the Democratic National Convention in August.

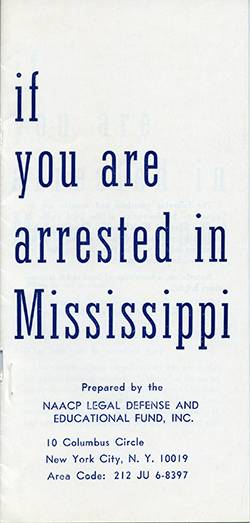

The effort was successful on many counts and expanded civil rights activism into areas of Mississippi that had previously experienced little activity. But the success came at a cost: By the end of Freedom Summer, there had been six known murders, 35 known shootings, four people critically wounded, at least 80 volunteers beaten, and more than 1,000 activists arrested.

The Digital Gateway includes a list of civil rights movement martyrs from Mississippi.

In 1961, Freedom Riders rolled through Mississippi to Jackson. All are jailed in Jackson, and then sent to the notorious Parchman Prison Farm. A few months later, local leaders ask SNCC to send organizers. Their task was to register voters. Left to right: Bob Moses, Julian Bond, Curtis Hayes, unidentified, Hollis Watkins, Amzie Moore, and E.W. Steptoe. Photo by Harvey Richards, 1963.

SNCC Digital Gateway Conference

The SNCC archives are at home at Duke, but through the Digital Gateway and the work of Gartrell and others, they are easily accessible for use by the public, scholars and school teachers in their classroom. “We’re proud the SNCC veterans see the Franklin Research Center and Duke as a place where their papers will be valued and are certain to be used,” Gartrell said. “There are always classes here at Duke using them. And we’re working with teachers’ groups to get these in the classroom.”

The March 23-24 symposium will involve activists, scholars and archivists reflecting on how SNCC’s organizing can inform current struggles for self-determination, justice and democracy. Friday sessions will be held at Duke’s Richard White auditorium; on Saturday it moves to NC Central University. For a full schedule, click here.