The fungus that causes athlete’s foot and other skin and toenail infections may have lost its ability to sexually reproduce as it adapted to grow on its human hosts.

Scientists analyzed samples of this tenacious organism, called Trichophyton rubrum, and found that nearly all belonged to a single mating type. What’s more, when they tried to set the fungi up with members of another mating type, they refused to do the deed, even after the scientists enlisted a variety of seduction schemes -- lowering the lights, cloaking the Petri dishes in plastic, flipping them upside down.

If this fungus can’t sexually reproduce, it can’t diversify, and if it can’t diversify, that may mean its days on this planet are numbered, said Joseph Heitman, MD, PhD, senior study author and professor and chair of molecular genetics and microbiology at Duke University School of Medicine.

But don’t expect toenail fungus to appear on the endangered species list anytime soon. “It is commonly thought that if an organism becomes asexual, it is doomed to extinction,” Heitman said. “While that may be true, the time frame we are talking about here is probably hundreds of thousands to millions of years.”

Though that timeline won’t be much help to the nearly 2 billion people who currently suffer from fungal infections of the skin and nails, the discovery that this species may be asexual -- and therefore nearly identical at the genetic level -- does highlight potential vulnerabilities that researchers could exploit in designing more effective antifungal medications. The findings appear online in the journal Genetics.

Fungal infections affect approximately 25 percent of the world’s population, and Trichophyton rubrum is usually the species to blame. People can pick up this infection by walking barefoot around swimming pools, showers or locker rooms, or by sharing personal items such as towels or nail clippers. Though there are plenty of over-the-counter powders and ointments along with prescription anti-fungal drugs on the market, most keep the infection at bay but don’t clear it. The infection is notoriously difficult to cure, and recent evidence suggests it may often be drug-resistant.

In this study, an international team of researchers decided to take a close look at the genetic makeup and sexual predilections of this fungus. They collected 135 different Trichophyton rubrum samples from around the world and determined their mating type by searching the fungal genome for either the alpha or the HMG domain, which is essentially the molecular equivalent of looking between a dog’s legs. The researchers were amazed to find that all but one of the samples were from a single mating type.

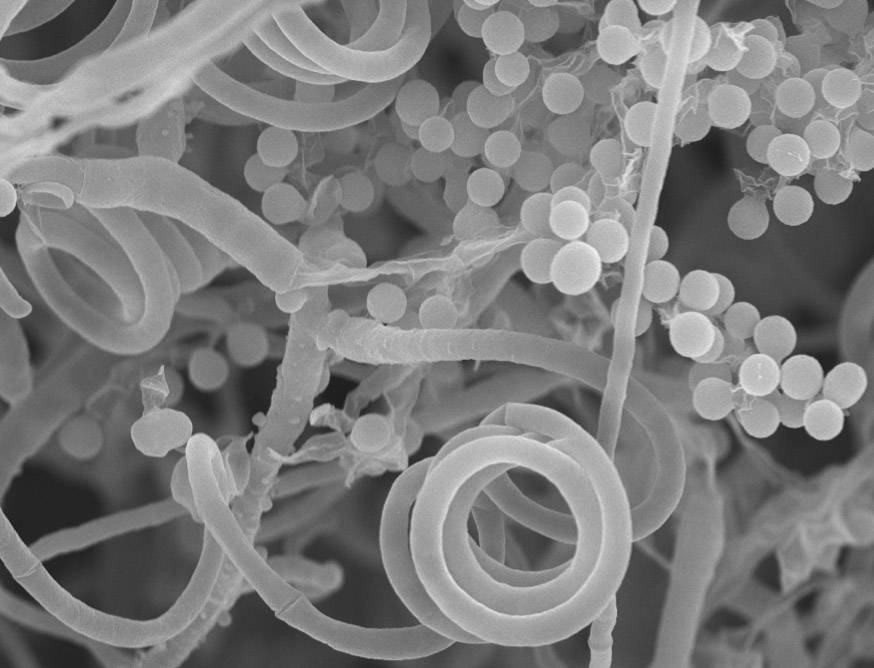

Though the findings suggested the fungi had become asexual, the scientists wondered if they would mate if given the opportunity. They placed the isolates in petri dishes along with a variety of potentially compatible mating types, under a variety of different conditions, and then waited to see if any magic would happen. After five months, the researchers looked at the petri dishes under a light microscope, scanning for the growth of coiled appendages that might contain spores. They didn’t see any.

Curious, the researchers sequenced the genome of the organism. They found that the organism is very clonal, meaning that different isolates (populations) are nearly perfect clones of each other, with little variation from one genome to the next. Any two genomes of Trichophyton rubrum are 99.97 percent identical, which translates to three differences out of every 10,000 genetic letters. Other fungi such as Cryptococcus are only 99.36 percent identical, differing in 64 out of 10,000 letters, making them 21 times more diverse than the toenail fungus.

“Such incredibly high clonality across isolates from around the world is remarkable, and suggests that this organism is very well adapted to humans,” said Christina Cuomo, PhD, senior study author and group leader for the Fungal Genomics Group at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard.

But there is a silver lining. Because the fungus is so clonal and could also be asexual, its ability to adapt further may be more limited than some other fungi. Thus, any new strategies that researchers could develop against this species may have a higher chance of success than those targeting sexual species, which are more capable of mutating or amplifying drug-resistance genes.

CITATION: "Whole Genome Analysis Illustrates Global Clonal Population Structure of the Ubiquitous Dermatophyte Pathogen Trichophyton Rubrum," Gabriela F. Persinoti, Diego A. Martinez, Wenjun Li, Aylin Döğen, R. Blake Billmyre, Anna Averette, Jonathan M. Goldberg, Terrance Shea, Sarah Young, Qiandong Zeng, Brian G. Oliver, Richard Barton, Banu Metin, Süleyha Hilmioğlu-Polat, Macit Ilkit, Yvonne Gräser, Nilce M. Martinez-Rossi, Theodore C. White, Joseph Heitman, Christina A. Cuomo. Genetics, Early Online Feb. 21, 2018. http://www.genetics.org/content/early/2018/02/21/genetics.117.300573

DOI: 10.1534/genetics.117.300573