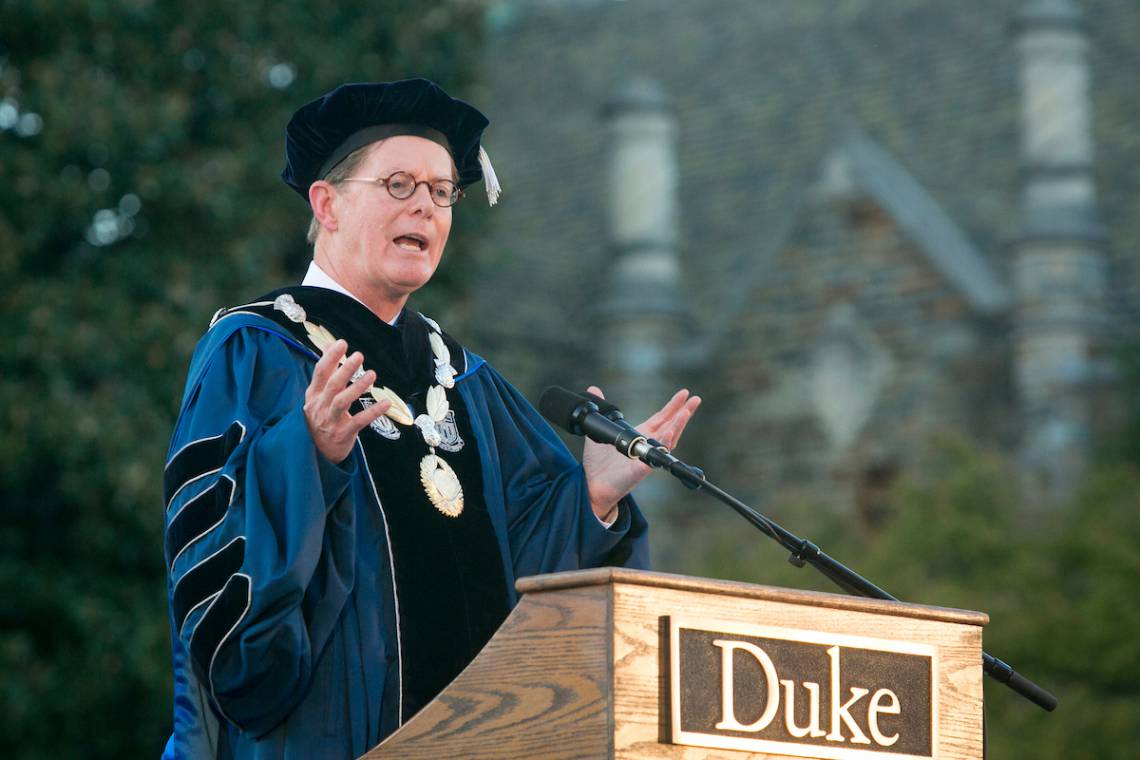

Vincent E. Price: 'Again We are Called Upon to Answer the Challenges of the Day'

Thank you, Jack, for the kind introduction, and to you, Ellen, for that heartfelt blessing. I also want to echo Jack’s appreciation of Nan and Dick, who provided visionary leadership to this university, and offer a special thanks to you, Amy, for sharing your friendship, wisdom and experience.

We commonly think of an inauguration as a beginning, and for me and Annette this does mark the beginning of a new life here as North Carolinians, as part of this vibrant university and wonderful city of Durham … and the conversion of our wardrobes to that luminous shade of blue that marks us forever as Dukies.

But what does this day mean for us together, as we gather today on Abele Quad, in front of this magnificent chapel, at the foot of these majestic trees? A beginning, yes, of sorts; but in an important sense no beginning at all. Rather another step, another iteration, in a long succession of events – and Presidents – that have come before.

Duke has been called “the university in the forest,” and those of you visiting for the first time can clearly see why -- even on beautiful Abele Quad, the center of Duke’s academic and community life, we are surrounded by towering trees, indeed many of them older than this campus.

In fact, this forest of trees was once largely abandoned farmland. Young loblolly pines were the first to seed the barren fields, still rutted with the scars of agriculture. They grew quickly into lonely stands, dropping needles to renew the soil and providing shade for hardwood species, which in turn matured into the thriving, diverse forest we see today.

Environmental scientists call this process succession, a natural regeneration whereby each stage of renewal prepares the land for the stage to come.

At Duke, we are the beneficiaries of a similar process of institutional succession, of continuity and renewal. Like the towering trees in Duke Forest, these magnificent buildings surrounding us today rose into the sky a little over 80 years ago, born on this land from the extraordinary vision of James B. Duke and President William Preston Few, who dared to see a university in a near-wilderness of pine and pasture.

The Gothic campus they brought to life was itself a rebirth and a renewal of Trinity College, which had taken the great risk of moving to Durham a generation before. This process of succession, of powerful and periodic renewal, can be traced directly all the way back to John Brown’s one-room schoolhouse in Randolph County, and as our architecture so clearly signals, indirectly to great traditions of learning stretching across continents and millennia.

Throughout our history, each iteration of this institution has risen with purpose to meet the great challenges of its day and has shaded and seeded the ground for the grander things to come. Each generation of Duke leaders has acted decisively in the face of ferment and turmoil to resist -- as President Few put it -- the mighty influences that would sway the university from its true course and to boldly accept the consequences of their choice.

Today, this university is again facing a world in ferment. We are again besieged by influences that would divert or distract us from our missions of teaching and learning, discovering knowledge, and of healing and serving society.

We face difficult questions about what role higher education should play in an increasingly globalized, interconnected world. We live amid concerns about the sustainability of our trajectory, in light of pressures placed upon students and their families. We hear criticisms from those who believe that elite universities are a barrier to -- rather than an instrument of -- the democratization of knowledge.

Again we are called upon to answer the challenges of the day.

So let us think of today not so much as a beginning, but as another renewal: both a renewed commitment to the values that guided the choices of our predecessors at Duke, and a renewed charge to make bold choices of our own, choices that will permit this noble university in the forest to thrive and to shape the course of a still-new century.

This renewal must begin where Duke began – in the classroom. Inspired by the great American philosophy of pragmatism, our forebears developed a thoughtful, far-sighted teaching model that blended the best of their past with what their present permitted, and what their future demanded. Their brilliant and broadly applicable system of departments, credits, and professionally accredited degrees is familiar to us because it became the paradigm of the modern research university.

And yet even as this model was perfected, the society that called it forth continued to evolve. Indeed, the research university system itself unleashed many of the most profound technological, economic, and cultural forces that have so undeniably altered our society: a society that, reflexively, now demands that we change, that we adapt. Today’s workforce, today’s human needs, today’s students – all have been transformed by the digital age. So too must our ability to elevate them and shape them for the better.

So, let us renew our commitment to lead in teaching and learning. Let us boldly set about the work of again blending the very best of our past with the full technological capabilities our present now allows, and with an eye toward the scalability and adaptability that our future will demand.

Duke has shown its boldness before. Are we bold enough now to invent new and creative ways to better adapt to and personalize every Duke student’s educational needs and interests? To offer them more efficient just-in-time and on-demand learning opportunities? Are we flexible enough to offer not only the finest residential education anywhere but also continuing access to learning, discovery and re-training throughout their entire lives as Blue Devils?

Our new century calls for a university audacious and visionary enough to fundamentally redefine learning and teaching in higher education.

I believe Duke can and will be that university.

We are similarly called upon today to renew our commitment to discovery. By transforming Trinity College into Duke University nearly a century ago, by reshaping and enlarging the departments of the college and founding new schools of graduate and professional study, our founders committed to fusing the finest in teaching with the most advanced research and scholarship.

This division of the research enterprise into disciplines has led – at Duke as it has elsewhere – to a wide array of transformative discoveries. Never has humankind understood more than we do today about our natural and physical worlds, our minds and behavior, our societies and cultures, our history.

But as our collective knowledge has grown, so too has the realization that the most pressing problems and far-reaching opportunities of our world tend not to fit into one discipline or profession. We must prevent our research from ossifying around practices that were designed to confront another century’s challenges, and that limit our ability to confront the emerging problems of today. The landscape of human knowledge and human challenge has changed; so too must our maps and tools for navigating them.

So, let us renew our commitment to opening our intellect, and the full generative power of our faculties, to the true shape of the world’s needs and opportunities rather than our established research conventions.

Duke has shown its boldness before in launching innovative interdisciplinary initiatives around – among others – the environment, the brain, and entrepreneurship. Few if any of our peers do it better. But I believe we must do more, and better yet.

Are we bold enough now to invent more productive and sustainable ways to organize and catalyze scholarship around pressing problems? Are we broad-minded enough to collaborate across the full range of scholarly perspectives, disciplined enough to drive resources to support this work, and flexible enough to alter our expectations of what “counts” as valuable research?

Our new century cries out for a university where the drive to discover is not hemmed by disciplinary logics; where philosophers work side-by-side with physicians and physicists; where nurses find inspiration in narrative theory; where mechanical engineers team up with marine biologists or musicians.

I believe Duke can and will be that university.

We are, finally, called upon today to renew our commitment to healing and to serving our surrounding communities. At each key moment of institutional regeneration, our predecessors understood and reconfirmed their obligation to marshal Duke’s teaching, learning, and discovery to positive social ends, and so we do today. We heal human injuries and illnesses; we work to heal division within our own community; and we use our skills and knowledge to aid healing and reconciliation elsewhere. We serve our fellow students and colleagues, our local community, and the world beyond to improve life and well-being for others.

This work begins here on campus. Our new century demands that we prepare ourselves for a diverse and often chaotic world, whose challenges, controversies, and crises do not stop at Duke’s gates. We need to work together to defend -- even seek out – voices that are different from our own. This is hard work, but if we are to heal the divisions in the world we have to open ourselves, honestly and deeply, to a diversity of perspectives.

One great advantage Duke has in this work is that we are part of a vibrantly global community. But we must be careful not to overlook the challenges and opportunities in our own backyard. James B. Duke called on us, in his words, to “develop our resources, increase our wisdom, and promote human happiness.” The truest tests of our commitment to healing and serving, the most accurate gauges of our resolve, are right here in North Carolina.

We have done much over the past decade to strengthen our service to this city and region. And yet, much good work remains.

Are we bold enough to consciously work to break down the division between what we do regionally and what we do globally? Are we humble enough to understand that we need not travel to the other side of the world to find communities in need, both rural and urban, or willing partners with whom we can work to propel human welfare, creativity, and fulfillment?

Our new century calls for a university that grounds its ambition to heal and serve the world in humility; that confronts its own problems as readily as it does others’, and that shows its most generous and supportive self to its own neighborhood.

I believe Duke can and will be that university.

Today, then, we are called upon to renew one of the last century’s great ambitions – this Duke University – for the new and very different century that lies before us. Ultimately, this renewal will require the active participation of every member of the Duke community: faculty, students, staff, alumni, and neighbors.

Together, we endow the university with our talents, our labor, our differences, our passion, and our knowledge; and in so doing, we join a long succession of men and women who have renewed the Duke University of their day.

We know it can be done. Consider the boldness of John Franklin Crowell’s moving Trinity College to Durham 125 years ago, when the institution was in dire financial straits, packing the 10,000 volumes of the library onto mule carts and sending them off on the trail to what is now East Campus. Or imagine James B. Duke and William Preston Few in the 1920s, picking their way on a cow path through fallow fields and having the audacity and the vision to dream of a Gothic campus rising on this hill.

We sit here for a moment’s rest at a point on the same trail, shaded by the very same hardwoods and pines, a trail that was at best obscure to the founders of this university. But they set our coordinates; they each cut their own section of this trail; they marched hard and gained so much ground for us.

And now it is for us to push further along, and to blaze a new path toward the brighter days ahead.