Humans Don't Use as Much Brainpower as We Like to Think

Animals had energy-hungry brains long before we did

DURHAM, N.C. -- For years, scientists assumed that humans devote a larger share of their daily calories to their brains than other animals. Although the human brain makes up only 2 percent of body weight, it consumes more than 25 percent of our baseline energy budget.

But a study published Oct. 31 in the Journal of Human Evolution comparing the relative brain costs of 22 species found that, when it comes to brainpower, humans aren’t as exceptional as we like to think.

“We don’t have a uniquely expensive brain,” said study author Doug Boyer, assistant professor of evolutionary anthropology at Duke University. “This challenges a major dogma in human evolution studies.”

Boyer and his graduate student Arianna Harrington decided to see how humans stack up in terms of brain energy uptake.

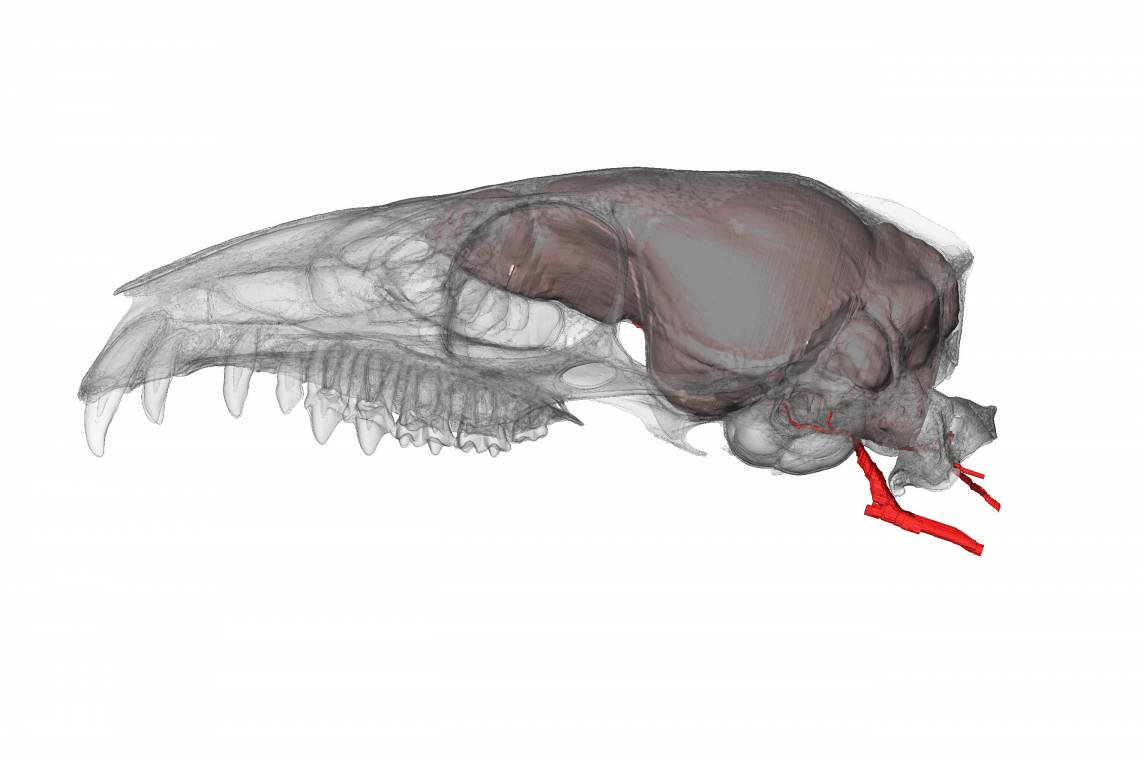

Because energy travels to the brain via blood vessels, which deliver a form of sugar called glucose, the researchers measured the cross-sectional area of the bony canals that enclose the cranial arteries.

By coupling these measurements with previously published estimates of brain glucose uptake and internal skull volume as an indicator of brain size, they examined seven species, including mice, rats, squirrels, rabbits, monkeys and humans. The researchers were able to show that larger canals enclose arteries that deliver more blood, and thus glucose, to the brain.

Then, using a statistical technique called multiple regression, they calculated brain glucose uptake for an additional 15 species for which brain costs were unknown, including lemurs, monkeys and treeshrews, primate relatives from Southeast Asia.

As expected, the researchers found that humans allot proportionally more energy to their brains than rodents, Old World monkeys, and great apes such as orangutans and chimpanzees.

Relative to resting metabolic rate -- the total amount of calories an animal burns each day just to keep breathing, digesting and staying warm -- the human brain demands more than twice as many calories as the chimpanzee brain, and at least three to five times more calories than the brains of squirrels, mice and rabbits.

But other animals have hungry brains too.

In terms of relative brain cost, there appears to be little difference between a human and a pen-tailed treeshrew, for example.

In terms of relative brain cost, there appears to be little difference between a human and a pen-tailed treeshrew, for example.

Even the ring-tailed lemur and the tiny quarter-pound pygmy marmoset, the world’s smallest monkey, devote as much of their body energy to their brains as we do.

“This shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise,” Boyer said. “The metabolic cost of a structure like the brain is mainly dependent on how big it is, and many animals have bigger brain-to-body mass ratios than humans.”

The results suggest that the ability to grow a relatively more expensive brain evolved not at the dawn of humans, but millions of years before, when our primate ancestors and their close relatives split from the branch of the mammal family tree that includes rodents and rabbits, Harrington said.

Previous studies calculated the amount of energy needed to fuel a brain based on neuron counts. But because the current study’s method for estimating energy use relies on measurements of bone, rather than soft tissue such as neurons, it is now possible to estimate brain energy demand from the fossilized remains of animals that are extinct too, including early human ancestors.

“All you would need to take the measurements is an intact skull and some of the neck vertebrae,” Harrington said.

What the data can’t show is whether energetically expensive brains evolved first, and then predisposed some groups of animals to greater mental powers as a byproduct, or whether preexisting cognitive challenges favored individuals that devoted more energy to the brain, the researchers say.

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (SBE-1028505, BCS 1440742, 1552848, DBI-1701714) and a Leakey Foundation Research Grant.

CITATION: "Scaling of Bony Canals for Encephalic Vessels in Euarchontans: Implications for the Role of the Vertebral Artery and Brain Metabolism," Doug Boyer and Arianna Harrington. Journal of Human Evolution, Oct. 31, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.09.003