This Week in Duke History: Trinity College Moves to Durham

Behind the scenes of how a Randolph County college came to thrive in Durham

Most colleges are forever tied to the location where they were founded. Harvard has always been in Cambridge. The University of North Carolina has always been in Chapel Hill.

But Duke has not always been in Durham. Instead, Duke and Durham chose each other in an intentional way.

In the 1880s, Duke’s predecessor institution, Trinity College, was located in rural Randolph County. The tiny town that grew up around the small college even took on its name, incorporating itself as Trinity, North Carolina.

At the same time, about 70 miles away, Durham was rapidly becoming a tobacco boomtown of the New South. The city had diverse population and economic opportunities for white and black citizens. City leaders were ambitious and determined for Durham to make its mark, and they saw higher education as a way to solidify the prestige and influence of their city.

Trinity College enjoyed a good academic reputation, but it was struggling financially and finding it difficult to attract students and faculty. John Franklin Crowell, a Yale graduate, had been named president of the college in 1887 at the age of 29. In addition to teaching economics and coaching the football team, Crowell had aspirations for Trinity. He managed to persuade both the trustees and the Methodist Conference that a move to an urban location would boost Trinity’s chances for success.

Crowell then began to approach North Carolina cities to gauge their interest in becoming Trinity College’s new home. In 1889, Raleigh offered the school $35,000, an amount deemed enough to cover the projected cost of the move, estimated at around $20,500, and the Methodist Conference approved the proposal.

But then the citizens of Durham stepped forward. Their civic pride had been stung when the Baptist State Convention had chosen to locate its Baptist Female University (later Meredith College) in Raleigh even though Durham had offered more money.

Durham officials of the Methodist Church urged local business leader and philanthropist Washington Duke to counter Raleigh’s bid. In early 1890, Washington Duke declared that Durham could match Raleigh’s offer, and that he would personally contribute an additional $50,000 for endowment. When news of this offer reached Crowell, he traveled immediately to Durham to meet in person with Washington Duke for the first time. Mr. Duke then suggested that if he was willing to put up the funds, Julian Carr might be induced to donate his fairgrounds, Blackwell’s Park, as a site for the college. Crowell went across town to put this request to Carr, who agreed at once.

Next, the trustees undertook the delicate matter of formally asking the citizens of Raleigh to release Trinity College from its agreement to move the college to the state capital. The request was granted, and the designated spot later came to be occupied by North Carolina State University.

The move to Durham did not go smoothly: it was originally scheduled for 1891, but the tower of the new main building collapsed, and the move was delayed a year.

Eventually, Trinity College packed up its college bell, clock, safe, and the several thousand books of its library, loaded them onto a railroad boxcar, and decamped to Durham. Crowell’s horses and Professor Pegram’s cow walked the distance. Crowell later wrote that while the actual distance was less than 100 miles, it felt like 10,000 miles psychologically.

The little town of Trinity had objected to the “removal” of its college; local farmers and boarding houses lamented the loss of income from students. In fact, most of the faculty chose not to make the move but remained behind in Randolph County to teach in the high school that opened in the old college building.

Trinity College opened in Durham on September 1, 1892, with 17 faculty members and 180 students – a large increase from its previous enrollment of 113.

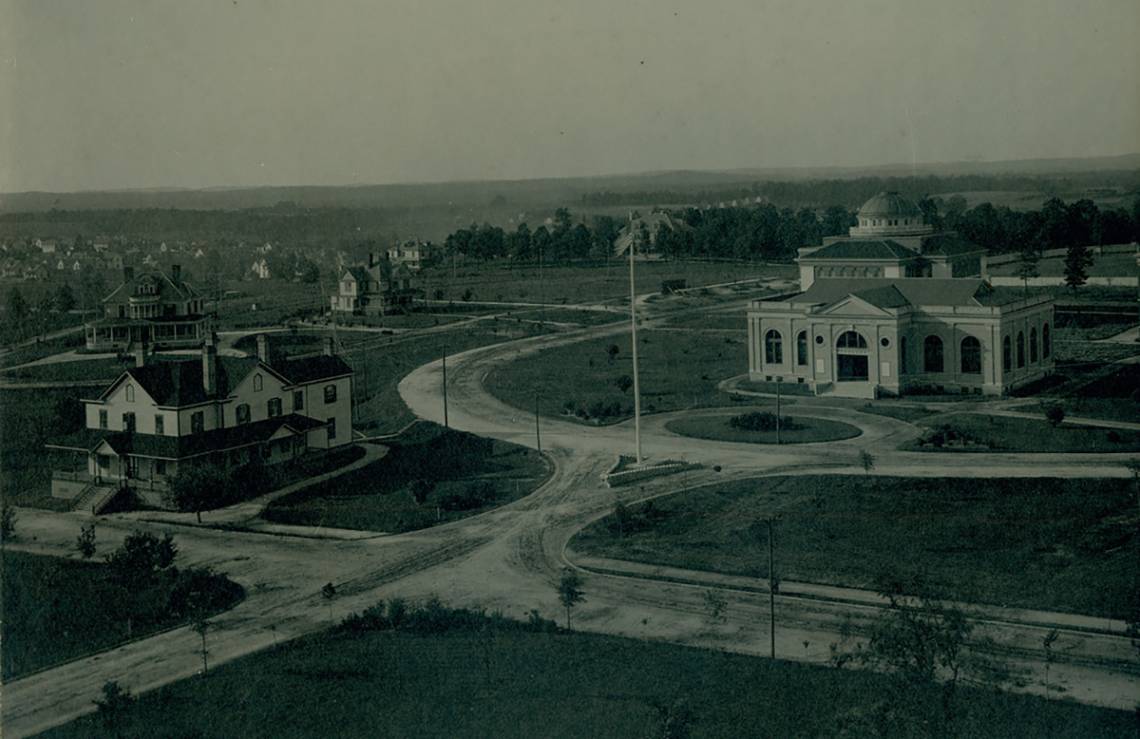

They were greeted by three new college buildings: a large building called Old Main, containing classrooms, the library, administrative offices, and dormitory rooms; the Technological Building, for which Crowell himself donated the funds; and the College Inn, which was the residential and social center of the college. There were also five houses for faculty on campus.

The move to Durham did not magically solve every problem for Trinity College; the college continued to face financial challenges. But by tapping into Durham’s urban energy, the college gained access to the wider world, and the strategic agreement between the college and its new home was the beginning of an enduring partnership.

Learn More: