Preserving the Priceless

Deep in Perkins Library, staff members protect Duke’s library treasures

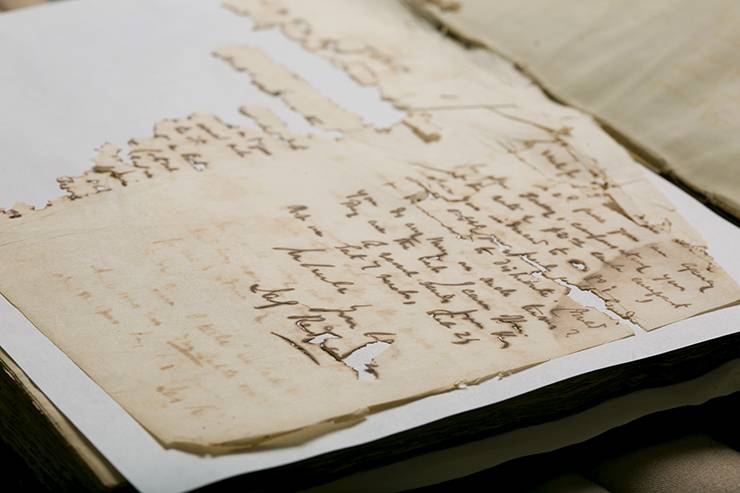

On a recent Monday afternoon in the Verne and Tanya Roberts Conservation Laboratory, Henry Hébert was battling a tear. Brushing gentle adhesive onto a yellowed page, the special collections conservator attempted to halt a rip’s slow march toward lines of looping handwriting.

That handwriting – complete with crossed-out mistakes and blotches where the author’s pen lingered on the paper too long – was put there more than 150 years ago by Walt Whitman. The book is a collection of the poet’s Civil War-era papers.

“This is a draft of an appeal he was making for an exchange of prisoners,” Hébert explained.

Working nearby, senior conservation technician Rachel Penniman overheard Hébert.

“Is that another Whitman?” she asked.

For the Duke Libraries team in the 15-year old lab in Perkins Library, protecting and preserving the priceless is nothing new. When a piece of Duke Libraries’ vast collection needs repair – no matter how common or curious – it goes to the Verne and Tanya Roberts Conservation Laboratory. Last year, the lab worked on 2,100 books and 2,247 other paper items, and each day brought surprises.

“We see it all,” said Beth Doyle, conservation services department head and the Leona B. Carpenter Senior Conservator who has overseen the lab since it opened.

To best understand work at the lab, consider these items found there on a recent day.

Finding a solution

Hébert moved the book of Whitman letters aside to show another project, one that illustrated the head-scratching problems the lab’s staff often faces.

After nearly a century, what was once the sturdy red cover that held together dozens of individual songbooks, had become a brittle mess. This book, cataloged as “Songs Used in Army Camps and Hospitals, 1918-1921” will get fixed but first, the staff had to figure out what method to use.

On a computer, Hébert worked on a report, detailing the damage, which included threadbare binding, numerous torn and creased pages and a spine that was missing large pieces. The report would get submitted to library curators, who would determine next steps, including answering: Would the songbooks stay bound together or would they be separated and catalogued individually?

“It’s a question of the best way to bring it back to life,” Hébert said.

Spanning the centuries

The lab’s metal shelves have held writings from nearly every era of recorded history. Cuneiform tablets from before biblical times have passed through. So too have centuries-old writings on vellum. On a cart nearby, there’s a reminder that not everything has that long a history.

Published in 2013, the 1,184-page hardcover “DC Comics New 52 Villains Omnibus” is a brick of a book.

“Here, feel how heavy this is,” Doyle said.

The book’s spine had come loose, leaving the cover barely attached to the pages. Doyle points to the reason. The whole thing was held together by flimsy paper.

“Of course that’s going to fail,” Doyle said. “That happens a lot with new materials.”

Like other books, the hardcover will get repaired and sent back into circulation.

“That’s always kind of amazing to me, to work on something that’s 500 years old and it’s in better shape than some things that are 40 years old because of the quality of materials,” Hébert said.

Built to preserve

While most of the staff works quietly, bodies still, gaze locked on delicate repairs, on this day, Rachel Penniman is in constant motion, cutting and folding stiff archival cardboard.

“I make a lot of boxes,” she said.

Not everything that comes into the lab needs to be fixed. Sometimes, the items just need a home.

Last year, the lab made 5,721 custom enclosures – essentially fancy boxes.

“Libraries don’t just collect books or manuscripts,” Doyle said. “They collect these weird and wonderful objects that don’t always sit on a shelf very well because they’re not square and flat.”

Penniman said the boxes are easy to make. It’s what goes inside that’s tricky. Each item has to be measured and foam padding cut to fit the item’s shape.

“You just need to be precise,” she said.

Recently, Penniman built a custom enclosure for ivory manikins in Rubenstein Library’s History of Medicine collection. The centuries-old, miniature anatomical models have hollow torsos that hold tiny, hand-carved organs.

Now, each figure rests snugly in Penniman’s assemblage of white foam and gray cardboard.

Fighting time

Recently, word reached the lab that a researcher was interested in seeing a book of letters from 19th-century abolitionist James Redpath. Making this happen wouldn’t be easy because the book had been in the lab for months with staff trying to figure out how best to save it.

The text was copied from original documents using iron gall ink. For well over a century, the acidic ink had eaten through the paper. Some of the book’s 484 pages were in decent shape. Others were so thin and riddled with holes they looked like worn lace.

“This is a little heartbreaking because I don’t know what we can do with it,” Doyle said.

Repairing the pages would take hundreds of hours of tedious work. Getting it digitized would also be an arduous process since each brittle page would have to be turned by one of the lab’s technicians while being photographed.

The researcher was able to see the book, but it’s uncertain if others will get a chance.

“For us to say you can’t have this because it’s too fragile, that breaks our heart as library conservators,” Doyle said. “That’s not our job. Our job is not to say you can’t touch this because it’s too precious.

“Our job is to say ‘Yeah, take it, see what you can do with this thing. Do something great. Learn something from it.’”