The Medici's Painter: Carlo Dolci

Nasher Museum exhibit reassesses a forgotten 17th Century master

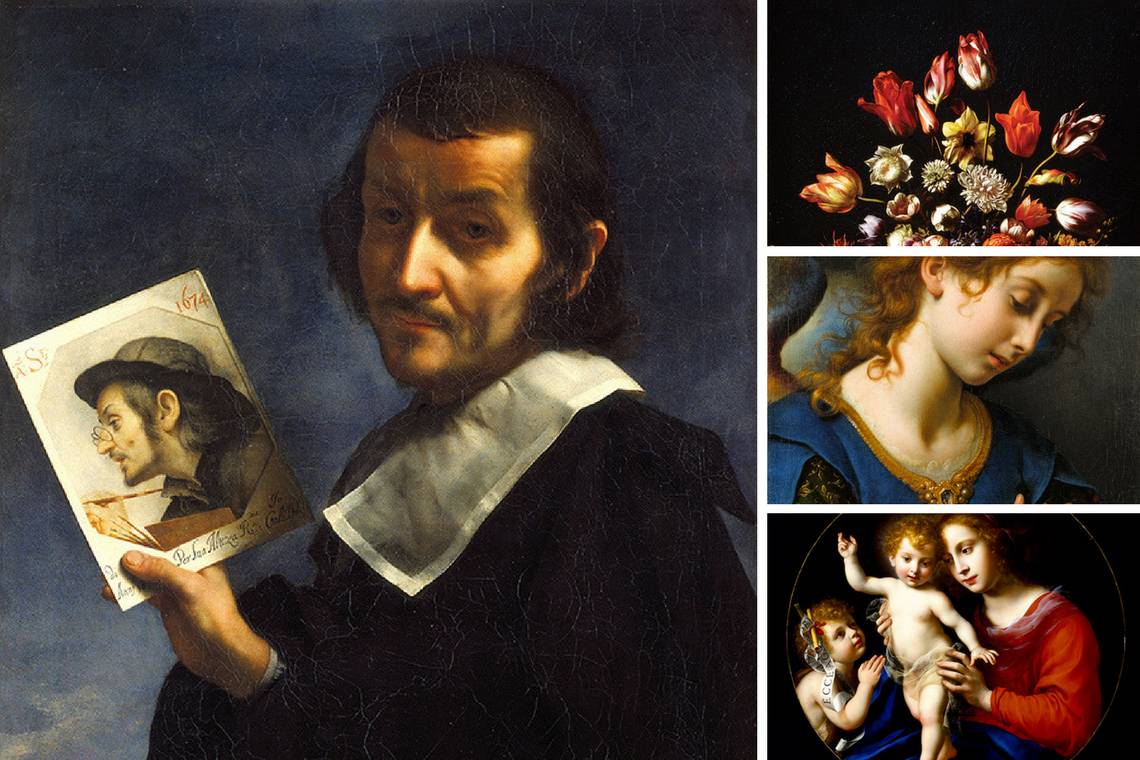

Left, Carlo Dolci, Self-portrait from 1674. 'The Medici's Painter' exhibit opens Aug. 24 at the Nasher Museum of Art.

The Nasher Museum of Art’s new exhibit, The Medici’s Painter: Carlo Dolci and 17th-Century Florence, is the country’s first-ever exhibition of the remarkable paintings and drawings by Carlo Dolci (1616-1687).

A favorite of the Medici court, Dolci was a celebrated and popular artist in his day, but his personal and original interpretation of sacred subjects fell out of favor in the 19th century.

The Medici’s Painter exhibit offers a reassessment of an Old Master painter whose reputation deserves to be restored. His meticulously painted and emotionally charged works that were carefully selected for this exhibition come from U.S. museums as well as important private collections and major museums in Europe.

Dolci was a precocious child, entering the workshop of Jacopo Vignali at the age of nine. Very early, his gifts as a painter were discovered by Don Lorenzo de’ Medici and other powerful persons in Florence, who recognized Dolci’s remarkable ability to render details from nature, especially facial features and hands, as well as complicated drapery.

As a boy and throughout his life, he was called “Carlino” (little Carlo), possibly because of his short stature and humble character. He was also extremely pious. If not diligently practicing drawing or developing his painter’s craft, he often could be found praying in Santa Maria Novella.

In 1632, when he was 16, Dolci opened his own workshop in Florence. One of his pupils was Filippo Baldinucci, who would become the leading connoisseur in Florence, and the author of the official biography of his “beloved Carlino.” Unlike most of his contemporaries, Dolci refused most commissions for large altarpieces and frescos. Baldinucci tells us that rather early in his career Dolci vowed to paint only religious works. A handful of portraits have survived, however, including the exhibition’s dashing Portrait of Stefano della Bella, which demonstrates Dolci’s skill in capturing the sitter’s personality as well as every fold and ruffled edge of the multi-layered linen collar.

In 1632, when he was 16, Dolci opened his own workshop in Florence. One of his pupils was Filippo Baldinucci, who would become the leading connoisseur in Florence, and the author of the official biography of his “beloved Carlino.” Unlike most of his contemporaries, Dolci refused most commissions for large altarpieces and frescos. Baldinucci tells us that rather early in his career Dolci vowed to paint only religious works. A handful of portraits have survived, however, including the exhibition’s dashing Portrait of Stefano della Bella, which demonstrates Dolci’s skill in capturing the sitter’s personality as well as every fold and ruffled edge of the multi-layered linen collar.

The Medici’s Painter also contains a rare still life, Vase of Tulips, Narcissi, Anemones and Buttercups with a Basin of Tulips. The Medici coat of arms in the middle of the gilded vase suggests it was a commission he could not turn down. Dolci’s real desire, however, and his spiritual mission, was to paint intimate depictions of divine subjects that would inflame the faith of those who viewed them.

The Medici’s Painter gives us an opportunity to study Dolci’s painstaking application of paint using ultrafine brushes, and only a few bristles, or the concentration it took to make tiny details look so real, as in the lace on the cloth beneath the Christ child’s feet in the foreground of The Virgin and Child with Lilies from Montpellier. One of the first things visitors will notice about a Dolci picture is his brilliant sense of color, achieved by his access to expensive materials, such as real gold and ground lapis lazuli, which accounts for the beautiful blues. There is often a high finish that gives the surface a smooth, enamel-like quality.

Dolci’s technique was time-consuming and exacting. He was notoriously slow, a perfectionist who might take as long as 11 years to finish a canvas to his own satisfaction. Another habit contributed to the inordinate length of time: According to his biographer, Dolci would recite the litany Ora pro nobis (pray for us) between each brush stroke and sometimes write inscriptions on the back of his canvas. The Medici’s Painter includes a fine example of such a canvas, so visitors can see Carlino’s tiny florid script.

“Dolci was an incredible colorist and an impeccable draftsman,” said Sarah Schroth, Mary D.B.T. and James H. Semans Director of the Nasher Museum. “Visitors will delight in his perfect rendering of hands and faces — and will be dazzled by his colors, such as the intense blue made from ground lapis lazuli.”

The Medici’s Painter is accompanied by an illustrated catalogue, published by the Davis Museum at Wellesley College ($35, Yale University Press). The catalogue was edited by exhibition curator Eve Straussman-Pflanzer, head of the European art department and Elizabeth and Allan Shelden Curator of European paintings at the Detroit Institute of Arts.