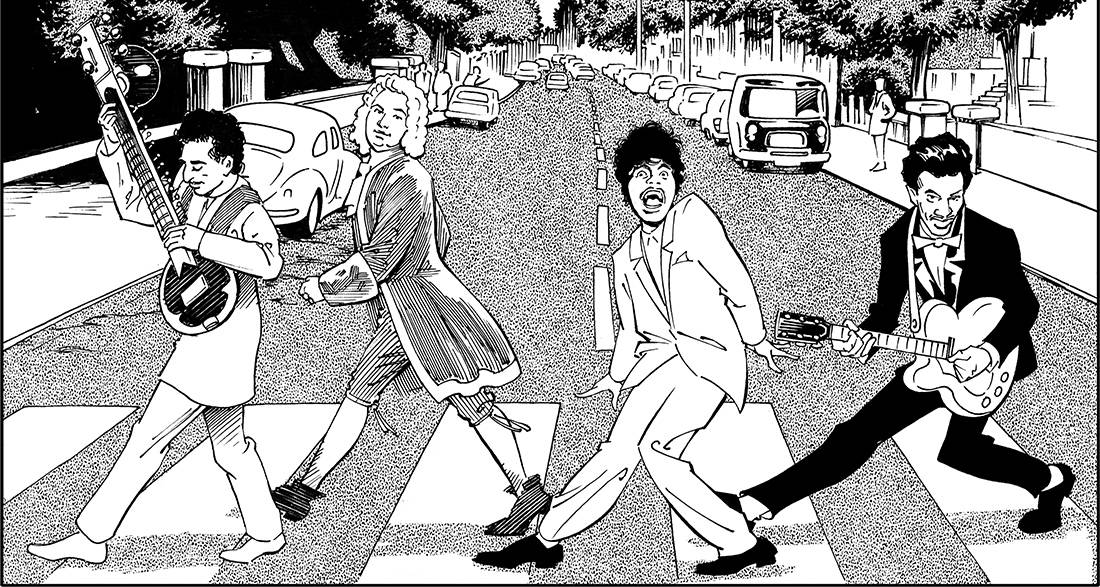

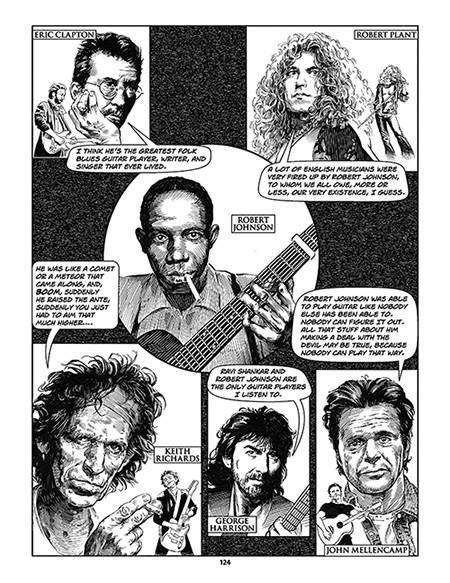

To borrow from Cole Porter, Tchaikovsky did it. Beethoven did it. Even Robert Johnson and Ray Charles did it. Creative masters all, they each appropriated music from others in their works and were borrowed from in turn.

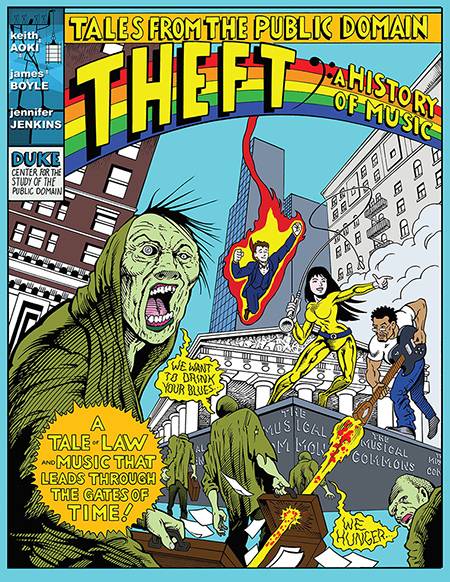

James Boyle and Jennifer Jenkins’ new scholarly comic book is a celebration of these and other musicians and composers who crossed barriers and built the playlist of extraordinary Western music from ancient Greece to classical to hip-hop. Published by the Duke Center for the Study of the Public Domain, “Theft: A History of Music,” brings these artists’ musical borrowings to the forefront, saying that instead of stifling creativity, such “thefts” were essential to musical cross-fertilization and creation of new genres.

But the book also comes with a warning: At every point of new musical innovation, there was resistance and efforts to control music, whether it was from philosophers, the church, or politicians. “These attempts at preventing borrowing have been going on for centuries and part of the reason is because music is very powerful. It raises a lot of passion. People get scared about change in music,” Boyle said.

Today, some of the challenges to the role of borrowing in music come from the law. Recent changes in copyright law and the culture of the music business directly attack the essential role of musical borrowing in producing new music.

“One of the questions we ask is, if we had the current rules in place 100 years ago, would we even have jazz, the blues, and rock and roll?” said Boyle, William Neal Reynolds Professor of Law at Duke Law. “And our answer is, maybe not, which is horrifying.”

The book builds on the success of “Bound by Law,” the 2006 comic book authored by Boyle, Jenkins and the late Keith Aoki, an artist and intellectual property scholar at the University of California-Davis School of Law. (See accompanying story). That book, which has been downloaded more than 1 million times, guided documentary filmmakers through potentially expensive legal intellectual property issues.

Boyle said the comic book form proved useful in presenting complex legal ideas. “One of the missions of the Duke Center for the Study of the Public Domain is to translate academic knowledge into information that artists, citizens and policymakers can understand and put to practical use,” Boyle said. “The format helped us give people the tools to understand, not just the law, but the entire creative economy in which their work is being constructed.”

Available online for free download, “Theft” is more ambitious than “Bound by Law,” covering nearly 2,500 years of musical history and connecting the variety of technological, political, legal, social and racial factors that shaped that history.

Each stop in history focuses on the tension in music between control and creativity. In ancient Greece, Plato argued that the state should actually ban mixing of the musical modes; he thought that remix would undermine both the cosmic order and social peace.

Each stop in history focuses on the tension in music between control and creativity. In ancient Greece, Plato argued that the state should actually ban mixing of the musical modes; he thought that remix would undermine both the cosmic order and social peace.

When notation was reinvented in medieval times, the church uses it to standardize the performance of the Mass and religious services.

But at every point, musicians found ways to subvert control. Composers start using notation to write more complex music that stretched the music beyond traditional bounds and created new genres. Secular troubadours and Renaissance composers had ideas of which the church disapproved, but that did not stop church musicians from borrowing from those secular, and often bawdy, sources and turning them into sacred religious music.

Changing technology also played a role, from Gutenberg’s printing press, which made the publication of music scores available to a wider audience, to the invention of recorded music, the radio, MP3s and digital sharing networks. Jenkins, director of the Center for the Study of the Public Domain, said that in many cases, predictions about the technology were “badly mistaken.”

“We all think the Internet changed music dramatically, but earlier technology did as well,” said Jenkins, who co-taught a class on music and law with music professor Anthony Kelley. “One of my favorite examples is the mass production of pianos. Suddenly middle-class families had pianos in their homes and people like me started to learn how to play it, but not all that well. So composers started writing music that could be played by people at home, which sounds very different than the music they were writing for professionals to perform.”

When the story turns to America, the means of control focuses on issues related to law and politics, and at the center of much of it was race.

When the story turns to America, the means of control focuses on issues related to law and politics, and at the center of much of it was race.

“We knew about the racially tinged resistance to black music, of course, but one of the surprising things in doing the research for the book was just how deeply music was part of a culture war based on fear of the other.” Boyle said.

“I think people are aware of the appropriation of African-American music or of the fact that African-American musicians not being sufficiently compensated. Even knowing that history, I was truly surprised at the depth and incendiary nature of the racial opposition to jazz, the blues and rock ‘n’ roll. Despite that resistance, music was continually moving back and forth across the color line. How can you listen to American music today and not think we are so much the richer for it? We’d be better off without jazz? The blues? Rock and roll? That is just crazy talk!”

“I found it humbling to realize, that in the face of intense cultural resistance, musicians kept pushing those boundaries because they love this music. In the process they kept drawing on each other’s traditions. They are the ones that make America the remix nation, which is what it still is today,” Boyle said.

The history also is a reminder of how unusual it is for musicians of all ethnicities to reap the benefits of their music. Boyle noted that Stephen Foster, whose blending of classical and African-American influences changed popular music in the pre-Civil War period, never received more than a pittance of the fortunes made by the publishers of his music. The three-decade period ending around the advent of digital music in the late ’90s might be the only time musicians became rich from publication and recording of their music.

While the music industry remains rightly concerned about digital piracy, Boyle and Jenkins draw attention to a less well publicized threat to the music of the future. A series of cultural changes in the music industry – the so-called ‘permissions culture’ – and several recent legal rulings have dramatically chipped away at the musical commons that musicians are free to use. The struggle between control and creativity is tipping toward the former.

While the music industry remains rightly concerned about digital piracy, Boyle and Jenkins draw attention to a less well publicized threat to the music of the future. A series of cultural changes in the music industry – the so-called ‘permissions culture’ – and several recent legal rulings have dramatically chipped away at the musical commons that musicians are free to use. The struggle between control and creativity is tipping toward the former.

These rulings included a verdict against Pharrell Williams and Robin Thicke for “Blurred Lines.” Here, Jenkins said, the jury was allowed to rule not just on the basis of specific musical elements in the music composition of Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up,” but on the basis of “total concept and feel.” It borrowed a general sensibility, mood and sound from Gaye’s song. The problem? Funk songs are going to sound like … funk songs.

In short, Jenkins said, the “common creative borrowing practices of the past may now be illegal.” The irony is that such an interpretation of the law stands in opposition to digital technologies that allow anyone with a computer or video recorder to reshape borrowed music, make it their own and distribute it online.

The main reason for optimism, they say, is the history of music itself, where creativity always struggles but seems to hold its own. “The message we end with,” Boyle said, “is ‘The staff of music is long, but it bends towards harmony.’”