Spring Breakthrough: A Week of Learning for Learning's Sake

Pilot program used creative topics to tackle scholarly issues with fun, food and magic

Students helped socialize two 6-week old golden retriever puppies as part of their class. The puppies, MATTOX and CHESSIE, are in training to become assistance dogs through the paws4people foundation. Photo by Megan Mendenhall/Duke Photography

Something had been missing in Sara Idris’ Duke education. She found it during Duke Spring Breakthrough, a pilot project at the university pairing students with Duke teachers studying unusual topics without grades or pressure.

Around 100 students, mostly first-years, spent Spring Break in Durham taking one of eight informal classes built around the concept of learning for learning’s sake. In Idris’ class with biology professors Mohamed Noor and Eric Spana, students explored the science behind science fiction and comic book stories such as Kong and Captain America.

Around 100 students, mostly first-years, spent Spring Break in Durham taking one of eight informal classes built around the concept of learning for learning’s sake. In Idris’ class with biology professors Mohamed Noor and Eric Spana, students explored the science behind science fiction and comic book stories such as Kong and Captain America.

“This experience reminded me of the joy of learning out of curiosity and for the sake of knowledge, and it gave me a drive and new-found motivation that I had definitely been lacking before spring break and that I plan to carry forward with me all throughout my Duke education,” Idris said. “I know for a fact that I want to further pursue biology at Duke -- though I originally had sworn to myself I wouldn't get anywhere near it! And I'm really excited about what the rest of my semesters here hold.”

As with the science fiction class, the topics could be light-hearted, but all delved into areas of strong scholarly interest. The Captain America discussion, for example, was a hook for a quick review of human genetics. A class on the musical “Hamilton” had students learning history and ethics, as well as trying out their creative writing and musical skills.

Whenever the week’s weather would allow, the students took their learning in the field, in the movie theater, at zoos or over meals.

Provost Sally Kornbluth said faculty and administrators are collecting assessment data but are already thinking about potential classes for next year.

Kornbluth spent the week visiting a number of the classes and said she saw “engaged and excited students” and faculty members who enjoyed “the opportunity to interact with highly interested students in a stress-free environment.”

“I think a side benefit that I hadn’t anticipated was that students found others whom they hadn’t known before, but who shared similar interests,” Kornbluth said. “In addition, students had the chance to have a good deal of interaction with the faculty both inside and outside of the classroom, which they really appreciated.”

Steve Nowicki, dean of undergraduate education, also said he saw a lot of excitement in the classes he visited. Nowicki, a biologist, also promised to teach a Spring Breakthrough course next year, called “The Birds and the Bees.” “Yes, it will be about sex,” he said. “Does that beat puppies?”

Confronting Climate Change in North Carolina

The biggest takeaway for students in Alex Glass’ sessions on climate change in North Carolina was the urgent need to address the issue. Glass, a geologist and popular teacher in the Nicholas School of the Environment, brought the global crisis home by focusing on the state’s vulnerability to development, agriculture, tourism and use of fossil fuels.

A cold, whirlwind trip to the Outer Banks augmented classroom discussions of the well-substantiated science behind the causes of global warming and sea-level rising.

“As an environmental sciences and policy major, I've had plenty of opportunities to read about climate change and learn about the threats that ecosystems and communities face,” said sophomore Claire Wang, who grew up in Utah. “Reading about a three-foot sea level rise is one thing, but walking on the beach alongside rows of abandoned houses that are already being washed away by the ocean is a completely different experience.”

A visit to the historic Cape Hatteras lighthouse, which was moved inland in 1999 to keep it from falling into the ocean, impressed Sangjie Zhaxi, a first-year student and native of Tibet, who took the class because he has witnessed snow melt on the mountains at home, where there is a lot of mining.

“One of the most important things I learned on the climate change trip is that how the narrow islands like the Outer Banks move over time,” Zhaxi said. “One side of the beach gets narrow over time, but the another side expands, so there is always a beach and it is a natural system. If we build concrete walls, roads, or houses on the beach, then the beach can't move naturally and ultimately we are destroying the ecosystem.”

Zhaxi said he was shocked to learn about the political and economic forces that prevent discussion of climate change. “This is also surprising, because this is a not a personal, or one country's issue,” he said. “This is a serious global issue that seven billion human beings and all other living creatures have to face at the end.”

For Glass, discussing the topic with the students gave him encouragement. “I have been very depressed about what climate change will mean for earth, humans and biodiversity,” Glass said. “However, spending five days with students who were so enthusiastic, optimistic and energetic about solving this issue has given me a renewed sense of hope and purpose in teaching this subject.

“I have also learned that the best laid plans can readily fall away due to bad weather!” said Glass, who cut discussions on the beach short because of the 30 degree weather and 40 mph winds.

Encountering Thoreau in the South

A class that focused on man’s relationship with nature wasn’t stopped by a cold snap that kept temperatures outside near freezing for the early part of the week. But that’s how Henry David Thoreau would have wanted it.

Thoreau is a central character in law professor Jed Purdy’s recent book, “After Nature,” which explores the political and social effects of the changing interaction of man with nature. In his Spring Breakthrough class, Purdy used Thoreau’s life on Walden Pond as a starting point to understand how place shapes our lives and beliefs.

The students read from “Walden,” but also Pauli Murray’s “Proud Shoes” to learn how Murray’s political, legal, social and religious activism was connected to her Durham upbringing. While the conversation started on how their study of Walden Pond affected their reading of “Proud Shoes,” Purdy also had the students consider the reverse: How did their reading of an African-American female pioneer activist shape their ideas about Thoreau and “Walden?”

Students said one highlight was a field trip to Eno River State Park, which many had never visited. Throughout the week, students said the class conversations were engaging.

“Professor Purdy does a fantastic job of facilitating discussion,” said one student, “allowing students to direct the flow of conversation often, while occasionally stepping in to point out some things he noticed.”

“Hamilton”: Music, History and Politics

For Noah Pickus, developing Duke’s inaugural Spring Breakthrough course "Hamilton: Music, History and Politics" was a family affair. His middle-school-aged daughter is a huge fan of the hit musical “Hamilton” and his wife is a research archivist in Rubenstein Library who made historical documents from Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr available for students to explore.

“These all came together to say, how do we teach about history and politics at the founding era and today, but use the musical, which so many students are in love with, as a way of getting them in to do this in a different kind of way than a traditional course that I might teach?” said Pickus, associate provost and a dean at Duke Kunshan University.

Over four-and-a-half days, students explored praise and criticism of the musical and studied the time period in which “Hamilton” takes place.

Students also learned how to write and perform spoken word. Pickus tasked students with using their research to compose their own narrative about an issue that was not presented in the musical.

“Writing doesn’t tend to get better just because you have more time. That was a struggle in the middle part of the course where they felt, ‘Oh my gosh, we’ve learned so much but how do we put it all together?’ But they all really came through and some of them rewrote their whole lyrics one day before they were due. But they all produced, I think, quite stunning material,” Pickus said.

One piece performed by freshmen Sonali Mehta and Tristan Malhotra explores the relationship between Aaron Burr, who is the villain in the musical production, and his wife Theodosia and their daughter. (Video below)

“Hopefully our song does a good job of showing more of Burr’s humanity and who he was outside of the guy who killed Hamilton,” Mehta said. “I have been involved with theater for a long time, but I’ve never really had to write a song like this before. So it was really cool just to have a couple of days where campus is pretty quiet, there’s not much else going on, just to really work on this and do all the research and take the whole project from start to finish.”

Socrates on Trial

For nearly 2,500 years, the Greek philosopher Socrates has loomed over Western civilization as the archetypal example of a wise and courageous individual who rather than compromise his beliefs faced the ultimate penalty.

For nearly 2,500 years, the Greek philosopher Socrates has loomed over Western civilization as the archetypal example of a wise and courageous individual who rather than compromise his beliefs faced the ultimate penalty.

For four days, classical studies professor Josh Sosin shared with students that there’s so much more to the story than what we think we know. Over dinner at his house, in walks along campus and in the classroom, Sosin took the students on a tour of Athens after the Peloponnesian War, and a question that has troubled intellectuals for centuries: Why did the world’s first democracy tarnish its values by executing one of the founding fathers of Western philosophy?

The class built to a final day of reading and discussion of the account of the trial by Plato, Socrates’ student and friend whose Apology provides the traditional account of Socrates’ defense.

But first Sosin and students reviewed other contemporary accounts, which provide a different picture of a city-state angered by the loss of a generation of young men in the war, betrayed by incompetent political leadership and reeling from the abuses of the Thirty Tyrants, Athenian leaders imposed on the city by Sparta following the war and led by one of Socrates’ students.

The seven students dove into the workings of the Athenian legal system, the use of rhetoric in trials, the nature of Athenian juries and most of all, the fallout from the disastrous war. “The demography of the city shifted,” Sosin said. “Nearly every male under age 50 was dead. The fallout ran for generations, and this shifted how people thought about young men. There weren’t many of them and they are seen as scary.”

Comfortable in the informal setting, the students spoke as much as Sosin, putting themselves in the mindset of the jurors and offering thoughts on how Athenian’s growing distrust of expertise affected Socrates’ trial. They talked about how some Athenians saw the trial as necessary to protecting Athenian democracy.

By the end of the week, the students -- only one of whom had extensive classical studies experience -- had shaped their own views.

“I like it when your comments reflect the parts I’ve underlined in my text,” Sosin said with a laugh during one class discussion. “It makes me think I got it right.”

Preventing Violent Extremism in America

For a class studying the rise of extremist groups, David Schanzer wanted his students to cut through the fog of political rhetoric on a volatile topic. He started with a trip to a mosque in Raleigh.

For many of the students, stepping inside a mosque was a first, and what they learned dispelled a lot of myths.

“That was one of the highlights,” said one student. “I learned more about Islam and misconceptions about it in this course than anywhere else.”

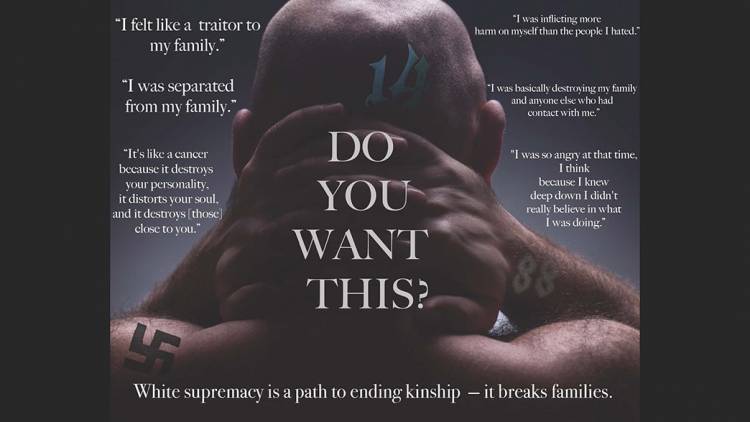

From a dinner at his house to a number of Skype interviews with policymakers and advisers in Washington, D.C., the class studied real-life examples of how people become radicalized, giving equal attention to the threat of white supremacy violence.

Then they started to do something about it. For final projects, the students broke into groups, developing a website and other messaging in a campaign to counter extremism. (See poster, above). The students developed tips to recognize the signs of growing extremism in friends and family members and offer advice on where to go for help in these cases.

The Biology of Popular Science Fiction TV & Movies

Eric Spana wanted his class to help with a problem: How tall was Captain America?

Eric Spana wanted his class to help with a problem: How tall was Captain America?

Spana had just spent 30 minutes outlining a plausible scenario for how scrawny Steve Rogers could be turned into a World War II superhero with strength, speed and metabolism surpassing any normal human. In discussing the comic book hero, biology professors Spana and Mohamed Noor in fact had given the 13 students a crash course in DNA repair, the role of myosin in regulating muscle development, CRISPR gene splicing technology, the amazing properties of cell-penetrating peptides, and path-breaking optogenetics research in which visible light is used to turn on cell properties.

But after all that, Spana still had several big obstacles to overcome. For one, how did 5’4” Steve Rogers become the much taller Captain America? How did all this resolve the sickly Rogers’ asthma and extensive heart ailments? And will any of these powers be inherited by any offspring?

For the next 30 minutes, students huddled together, searching the Web, reading literature both scholarly and fan-based. They start discussing issues such as what would be the effect of myosin deficiency on Rogers’ ailing heart? Can bone cement explain how Captain America was taller than Rogers? What would it take to get Captain America, whose metabolism was four times the norm, drunk? (This is a popular question among nerds. The answer, the students found based on a formula incorporating his higher metabolism, is that he would have to drink a gallon of beer in one minute.)

Spana has given public talks on the genetics of Harry Potter and the biology of Marvel Comics, while Noor has a talk on evolution in Star Trek. In the class, they used science fiction in literature, TV and movies to take the students on a tour of some of the most pressing questions in biological and evolutionary science. After watching “Kong: Skull Island” for example, the students returned to class to explore research on “island gigantism,” (see video) including Darwin’s observation that island species must be most closely related to species found on the nearest mainland, one important piece of evidence supporting evolution.

Free Beer And Other Forces That Get Us to Misbehave

The students in professor Dan Ariely’s behavioral economics class were robbed by a master.

To show how humans can easily get distracted, Ariely brought in Apollo Robbins, a professional pickpocket, magician and entertainer, whose popular TED talks explore how misdirection affects human behavior and decisions.

Getting their pockets picked was one of the highlights of a class that included a visit to Ariely's lab where his psychology experiments have been the source of his best-selling books on irrationality, dishonesty and the logic of human motivations. Those experiments also are the source for the many personal anecdotes that he told during the class.

The lesson of the class is that real-world phenomena that appears to be unquantifiable can in fact be quantified in a useful way. Students delighted in the lesson.

“Behavioral economics was a fascinating topic but I think it was Dan himself that made the topic even more engaging and personal,” one students said about the class.

Puppies!

Evolutionary anthropologists Brian Hare and Vanessa Woods put their 14 students through the tough assignment of spending much of the week cuddling with puppies and playing with older dogs.

The fun all had the serious scientific point of asking what the domestication of dogs and other species can tell us about canine and primate evolution.

Visiting the Durham animal shelter, meeting service dogs and their trainers, and cuddling with puppy participants in Hare’s Canine Cognition Center, the students studied canine behavior, along with that of their human friends.

The class asked what do we think is attractive, which has significant evolutionary implications. Hare and other researchers believe that rather than humans domesticating dogs, the canines domesticated themselves as an evolutionary strategy for longer, safer lives. In evolving from wolves, dogs took on more floppy ears, shorter, curlier tails, shorter snouts and smaller teeth, all of which added to their appeal to humans. Hare and Woods asked the students why these changes appeal to us, and what evidence do we have from other domesticated species that might shed additional light on the topic?

The week concluded with a visit to a Siler City goat farm where students engaged with a different kind of cute, domesticated animal and to the North Carolina zoo to visit chimpanzees, which along with bonobos are the closest relative to humans.

At the zoo, the students received a quick and startling lesson about primate behavior: Kendall, the leader of one of two groups of chimps at the zoo, appeared at the far end of the enclosure, saw and recognized Hare and in a matter of seconds raced to the window to slam his hand in front of Hare and the students.

“As a general rule, chimpanzees will not engage with humans watching them at the zoo,” said Hare, who has met Kendall several times during around a dozen trips over the past decade. “But if you’ve met the chimpanzee at the back end of the enclosure (closed to the public), they remember you and will come to you.”

The slamming of the wall was typical chimp behavior asserting Kendall’s dominant position. As soon as that was over, Kendall returned, sat in front of Hare, and the two shared a long, quiet and friendly interaction. (Video, above)