The image remains unforgettable: The body of a young African-American boy, his skull smashed in, one ear clipped, one femur – the strongest bone in the body – broken, lying in an open casket because Emmett Till’s mother wanted all of America “to see what they did to my boy.”

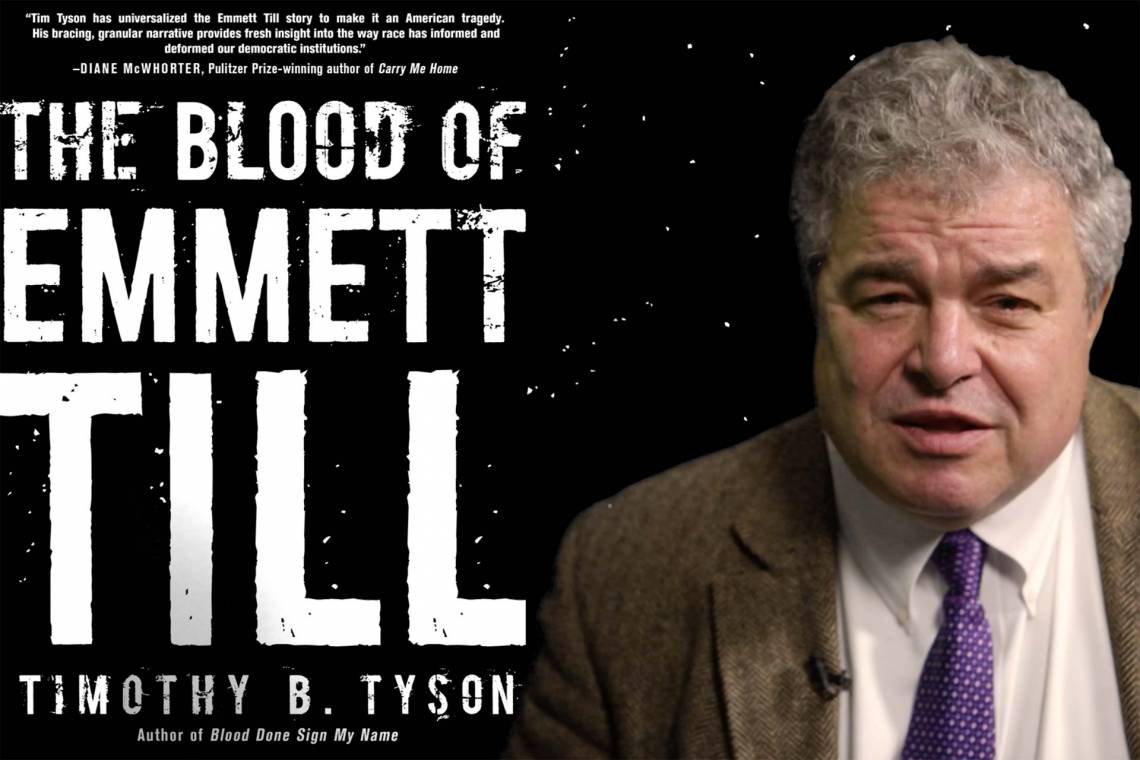

Six decades after Till’s murder, Duke professor Tim Tyson is retelling the story with new information in a book, “The Blood of Emmett Till.” And while Till hasn’t been forgotten, Tyson’s book will make many people rethink what they believe they know about the story.

The book has already received significant attention for a not-surprising but still important revelation: Carolyn Bryant, the woman who accused Till of physically assaulting her, confessed to Tyson “that never happened.”

The Duke professor talks about why the woman at the center of the Emmett Till trial opened up to him. Video by Julie Schoonmaker

But Tyson wants readers of his book to focus on a larger issue: How the bravery and courage of Till’s mother Mamie Till and the efforts of a growing African-American community in Chicago “turned a horrifying moment into a nationally transformative civil rights movement.”

“Carolyn Bryant is not the center of the story,” said Tyson, a senior scholar at the Center for Documentary Studies. “She’s just one of a whole lot of new sources in the book. I knew it was important she revealed it, and it gave me insight into things, into her family culture.

“But her statement was a side issue. Emmett Till’s story wasn’t in itself unusual. Our history along the color line is bloody. What is different about the Till case is a courageous mother turned private agony into a public issue and used it in the power of African-American institutions in Chicago as a giant megaphone that built the national infrastructure for a civil rights movement. It was one of the movement’s birth places. Just 100 days later, Rosa Parks refuses to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus.”

The book, Tyson said, “is not just about a tragedy. It is a horrible murder, but it’s not the end of the story. What happens out of black Chicago and across the country is a kind of resurrection. In that sense, it’s a hopeful story.”

Finding that hope was essential to the book, Tyson said. To write about one of the most brutal racial murders of a brutal period, Tyson knew he would be working with dark material. He said he found himself procrastinating.

“I didn’t want to make it happen in my imagination,” Tyson said. “I knew I couldn’t write it without imagining it, and I did not want to imagine the lynching of Emmett Till. I wrote the first draft of the book and set it down and when I read it again, I realized that in the book about a lynching I had left out the story about the killing. I hadn’t planned on it; I just refused to tell it.”

What helped him finish the story was the realization that he had support, as a historian from “mentors, teachers, family, from the living and the dead. They’re with you. It can’t hurt you. I told myself this is important and that I had a lot of resources that I wasn’t calling upon.”

Emmett Till

Emmett TillThe Duke classroom is one place where Tyson has always been able to raise issues of racial violence. In addition to the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS), he also has an appointment at the Divinity School. At CDS, he teaches a class on “The American South in Black and White,” unusual in that it includes students from Duke, NC Central University, UNC-Chapel Hill and adult community members, all of whom bring their life experiences to the discussion about contemporary racial issues.

The circumstances of the Till case may seem alien to young students, but Tyson said they quickly see a connection to contemporary shootings of young African-Americans such as Trayvon Martin and Tamir Rice.

“They may have a hard time getting their head around how deep and volcanic race and sexuality were. The violence that was aroused by any thought of a connection between a black man and a white woman is hard for students to grasp, in part because it was so deeply insane. The people who expressed it didn’t even know where their revulsion came from. They couldn’t tell why they felt that way. But otherwise racial violence isn’t beyond (students’) world. It’s not foreign to them at all. It’s a major public issue for their generation.”

Tyson previously wrote in “Blood Done Sign My Name” about the 1970 murder of Henry Marrow, a young black Vietnam War veteran by white men in Tyson’s home town of Oxford, North Carolina. Tyson was 10 when the murder occurred and was a young witness to the months of activism that seared through the segregated town.

He said with both books, “The heart of the matter is what people were able to do out of this tragedy. If history doesn’t speak to the new day, it’s just trivia. It’s just old stuff. The purpose of studying history and doing all that digging and plumbing the depths of things is to recreate the world so reader can know it.”

And, he added, as he sees a new generation of activists responding to the murders of young African-American men, he hopes the Emmett Till book will encourage them not to be paralyzed by tragedy but to take action.

“I hope readers take away the message that the brutal tragedy of a broken word is not the final word in reality. People have the power in our culture, we have the material we need to mobilize against this kind of racial injustice and change this world. The African-American freedom struggle has reshaped our world. We’re not where we need to be. But it’s not Jim Crow Mississippi in 1955 either, and it would still be that way if people sat on their hands instead of rising up and organize and build institutions that they organized into power.”