Downtown Sparks Ideas

Nearly 3,500 Duke employees work in downtown Durham, boosting innovation

Echoing through seven floors of a vacant, historic building, sounds of saws sheering through metal and the clanging of hammers filled one of downtown Durham’s biggest renovations projects.

Open windows and entryways at the 68-year- old Liggett & Myers cigarette factory, now The Chesterfield, allowed the sounds to spill onto North Duke and Main streets, an audible cue of the future for the city – and Duke.

The economic and cultural renaissance of downtown, supported by $1.2 billion of private and public investment since 2000, is showcased perfectly in The Chesterfield, where Duke will lease about 100,000 square feet for engineering and medical research. The Chesterfield, billed as a centerpiece of Durham’s life science community, is set to open in January 2017 with a goal of spurring ideas and products that may change the world.

At The Chesterfield’s center is an atrium meant to attract the building’s bright minds to one of its brightest spaces. A 3,500-square-foot skylight shines sun on a lobby where employees and visitors will meet, mingle and discover medical or engineering breakthroughs in a space being referred to as a “knowledge community.”

“Not only do you get to interact with people easier and more informally, but students, faculty and others are working together that creates a sense of community,” said Ken Gall, a professor and chair of the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science who will move to The Chesterfield. “When you interact with people who work toward similar problems and challenges, that gives you a sense of confidence

in your work.”

Duke has had a downtown presence since the 1970s with Duke University Press employees at Brightleaf Square. During the past five years, the number of Duke employees working downtown, from Brightleaf to the American Tobacco Campus, has increased from nearly 2,000 to 3,500 and will continue to grow even more. As Durham continues to evolve as a city, the collaborative nature of science and technology is getting a boost from the collection of faculty and staff moving downtown.

“Durham is very diverse in thought, economically diverse, ethnically diverse, and the area where you can collaborate with those people is already here – it’s downtown,” said Scott Selig, Duke’s associate vice president of capital assets and real estate. “You can run into someone working at a gaming company or sequencing proteins just anywhere. It’s an open environment of ideas.”

Looking Back to Look Forward

Duke community members meet and mingle during the grand opening of The Bullpen in August 2015. The space acts as one of Duke’s main hubs for innovation and collaboration between students, faculty, staff and community members.

In August 2015, Duke’s Innovation & Entrepreneurship Initiative (I&E) moved into a downtown Morris Street tobacco building built in 1916. I&E’s office, The Bullpen, is a focal point of the university’s innovation and entrepreneurship efforts and foreshadows Duke’s involvement in Durham’s growing Innovation District, a span of 1 million square feet across 15 downtown acres.

The Bullpen provides just under 13,000 square feet of workspace for collaboration among Duke community members and Durham’s entrepreneurs and organizations. In May, it served as a meeting space for Moogfest, a gathering of artists, entrepreneurs, futurist thinkers, musicians and engineers.

“We’re getting wiser about solving problems we have in the world because we’re not limited to one answer from one person,” said Marie-Angela Della Pia, I&E’s community director who facilitates learning and interaction opportunities between Duke and Durham. “The spirit of entrepreneurship is finding answers from a lot of different people with a lot of perspectives.”

Since opening, The Bullpen has connected disciplines spanning social sciences, law, anthropology and medical research. Duke community members, including students, have used the space to dream up projects from a sensor that detects displacement of a runner’s heel to an antiperspirant hand lotion.

“You come for the space but stay for the collaborative possibilities,” Della Pia said.

It’s a lesson learned by Tatiana Birgisson, a 2012 Duke graduate who, as a student, founded the energy drink company MATI Energy with the help of I&E and stayed in Durham because of the entrepreneurial spirit she found at The Bullpen.

“Putting Duke resources close to the startup scene creates a connection between Duke and a density of startups, which is incredibly important,” said Birgisson, who now mentors and collaborates with students at The Bullpen. “The culture of entrepreneurship intensifies the closer you get to its nucleus.”

That’s a tangible outcome seen by Nicholas Katsanis, the director of the Center for Human Disease Modeling and Jean and George W. Brumley Professor of Cell Biology and Pediatrics. Since moving into downtown’s Carmichael Building at 300 N. Duke St. a year ago, he has harnessed partnerships with other Duke faculty.

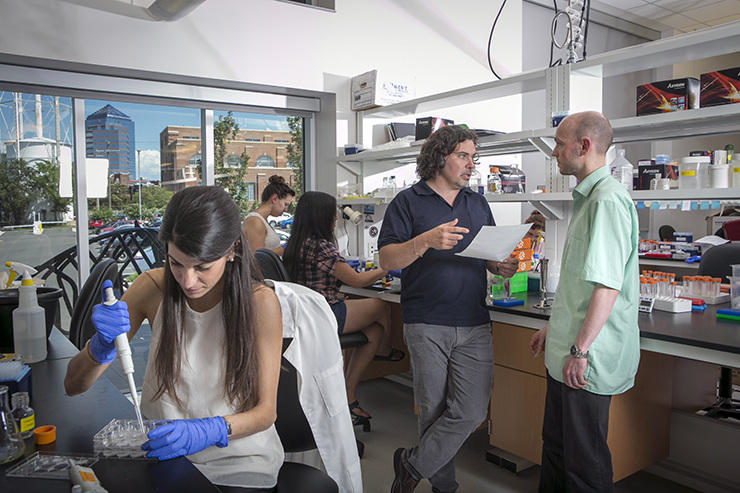

Nicholas Katsanis, center in black shirt, discusses research plans with a colleague in his downtown lab space located in the Carmichael Building at 300 N. Duke St.

On campus, Katsanis was far away from peers in the Duke Molecular Physiology Institute, but now he’s sharing labs and space with fellow researchers in Carmichael, allowing for daily conversations and connections. By sharing close proximity, Katsanis and his faculty have been able to accelerate several research projects on disorders such as glaucoma. He’s also in the early stages of a startup, Rescindo Therapeutics Inc., which focuses on accelerating drug target discovery for genetic disorders.

“If we weren’t here downtown, I don’t know if I’d have the proximal tools available to launch the company,” Katsanis said. “Here we have capacity to use an incubator model to help the company stand on its feet and promote interaction between scientists working for the company, my own academic unit and other Duke investigators.”

With the potential to meet academics and non-academics alike within walking distance of his lab space, Katsanis said an important benefit of being downtown is simply having the chance to share information about what he and Duke are up to.

“Being in the heart of Durham gives us opportunities to demystify our work to the general population,” he said. “By and large, scientists have shied away from the responsibility of reducing the opacity of the research enterprise and engaging the broader population. Here, we have an opportunity to change that.”

Embracing Collaboration

A rendering of the Chesterfield shows a glimpse of what the inside of the seven-story Chesterfield building will look like once completed in 2017.

By 2017, Duke faculty and staff will take up about 1.3 million square feet of space across downtown, and in 2018, Duke will take on 200,000 more square feet. About 55,000 square feet will be in a new 27-story high rise called One City Center and an additional 150,000 in a building being constructed across from The Bullpen near the corner of Morris and Roney streets.

“Duke is always looking for ways to integrate into the fabric of Durham, and I can’t imagine working to collectively solve problems we face as a community without Duke at the table,” said Shelly Green, president and CEO of the Durham Convention & Visitors Bureau. “One of Duke’s best resources is its really smart people that care about Durham and the world.”

Tallman Trask III, Duke’s executive vice president, said that the university’s use of downtown space offers flexibility to grow and allows researchers and faculty access to work hand-in-hand with outside companies.

“There’s a lot more university-corporate mixed activity than there used to be because a lot of corporations have cut back on research and development expenditures and are looking for partners,” Trask said. “You find the same thing happening in Cambridge and major cities like St. Louis or Baltimore. Biomedical, medicine and engineering partnerships are expanding all the time.”

Trask estimates that in the past 20 years, downtown Durham’s available office space has dropped to just under 5 percent due to an influx of businesses and entrepreneurs snapping up space and finding themselves working within blocks- if not feet – of each other.

When Ken Gall, the professor and chair of the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science, moves into The Chesterfield next year, he’ll shift his office and lab space from campus’ Hudson Hall to about 6,000 square feet in the renovated building.

Ken Gall, chair of the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science, will be among the first Duke employees to move from campus to the Chesterfield building.

Once there, Gall may bump into staff from BioLabs North Carolina, a biotech co-working facility that will have 42,000 square feet in The Chesterfield.

Gall said having close access to others is pivotal for research and ideas to flourish. He’s founded two medical device start-up companies that have commercialized university-based technologies, experience pivotal to promote innovation and entrepreneurship among Duke colleagues.

“More people are looking at research and asking, ‘how can I turn this into a product that might impact society in the near term?’” Gall said. “Being embedded downtown in a growing city that has this entrepreneurial growth helps to spark interactions and build a sense of community around startups, small labs and the research we’re doing.”

In Durham and elsewhere around the country, this marriage of academia and private enterprise is taking off. Cross-collaboration isn’t a luxury occurrence. More than ever, it’s becoming a necessity.

“If there’s a problem you want to go after, you realize you don’t have to work in isolation anymore,” Gall said. “It’s an exciting time.”