Family farms are central to American political mythology. Smiling, attractive families working the land and tending animals are a staple of campaign commercials and stump speeches. Rural family life enjoys exceptional deference and celebration, fetishization even.

Our collective political mythology portrays the family farm as a form of reproduction that is authentic, healthy, and sustainable — the way we lived before modernity, urbanization, and industrialization corrupted both family life and farmland. Given the inhuman scale of ecological crises like climate change and food insecurity, family farming offers a seductive mythology, anchored in a fantasy of permanence and human scale. But it’s a mythology all the same, and one largely disconnected from the history of rural family life in America.

The truth is that life on farms from the Atlantic Seaboard to California bore little resemblance to the nostalgic ideal suggested by contemporary imaginings of the family farm. Populations were transient, families were chaotic and broken, sexual taboos were flouted, and the romanticism of “Little House on the Prairie” pioneering collapsed on its first contact with the material realities of violence, deprivation, disorder, loneliness, and longing that better characterized the peripheries of America’s agricultural empire.

Agrarianism has an enormous footprint in American history, dating back at least to Thomas Jefferson’s famous celebrations of the yeoman farmer in his “Notes on the State of Virginia.” Jefferson’s agrarian rhetoric was good politics even then. An enormous portion of the population labored in agriculture — freely and in bondage — and flattering smallholders with talk of intrinsic virtue built broad-based support for the policies of agricultural expansion.

The kind of agriculture to be expanded remained a source of vitriolic and politically defining dispute. Cotton monocultures, largely tended by slaves, rapidly depleted soil nutrients. With each passing decade, the epicenter of cotton production moved steadily westward, as slavers abandoned old plantations to start anew on unbroken land further west.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, the throne of the cotton kingdom sat in the Mississippi River Delta, but its frontiers extended well into Arkansas and Texas. Similarly, Northern settlers moved westward in waves, with farmers seeking fertile bottomland for bumper crops of corn, a crop they transformed into whiskey and pork for Eastern markets.

By the middle of the 19th century, an emergent grain-livestock complex stretched from Ohio to Colorado. In both North and South, agricultural expansion entailed the violent dispossession of indigenous populations, the managed integration of Western lands into settled agriculture, and the organization and importation of human populations necessary to both objectives.

Agricultural expansion depended not upon the settling of America, but on continuous and fitful cycles of dispossession, settling, unsettling, and resettling. Nineteenth-century populations were highly mobile, and they often carved out ecologies and communities that were precarious, fragile, and intentionally temporary. Many farmers planted on a particular plot of land always with an eye on the exit: the fantasy of cheap, fertile land out West. Others went West, and when they found it, immediately fled back East in shock.

For the millions of slaves laboring in Southern agriculture, the notion of permanent settlement ran afoul of the stark realities implicit in the traffic of souls: Slavers sold their slaves to cover debts, to hedge declining labor productivity as slaves aged, to dispose of difficult or rebellious slaves, and for a thousand other reasons. The movements of individual slaves often demonstrated a complex pattern not of settlement and permanence, but of internal flow, migration, and transience that follows precisely the trajectory of cotton cultivation: southwest and downriver. For indigenous populations, the history of agricultural expansion was the history of repeated dispossession and forced resettlement on increasingly marginal lands.

Such highly mobile populations meant that family structures tended toward flexibility and contingency on the frontiers of agricultural expansion. On Northern farms, the family retained centrality as the unit of labor organization and many people traveled West as families.

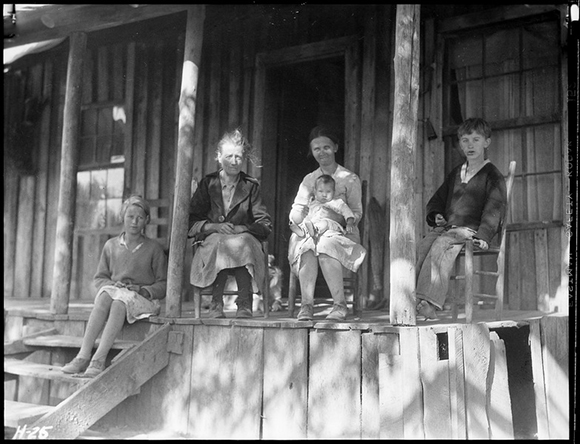

Depression-era documentary photographer Lewis Hine took this photo of a farming family in Tennessee. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

But these families bore little resemblance to the farmer-homemaker model we often falsely ascribe to family farms. Rather, such families were sprawling, maximalist, and multigenerational affairs with only rough notions of gendered divisions of labor. Men were responsible for staple and field crops, and women were responsible for dairying, poultry, produce, cooking, and cleaning. Ideally, men’s labor generated a lump sum at harvest that covered the cost of the next year’s planting; women’s labor, by contrast, generated a steady stream of income year round — sometimes called “egg” money — to cover daily expenses. Regardless, flexibility was the watchword of the day. With survival at stake, everyone worked — gendered ideals be damned — even if it meant women contributed field labor during harvest and men mended their own socks. Neighbors pooled labor, and farms took on regular hired hands, and this too created kinship beyond blood relations.

High morbidity rates, particularly during childbirth, meant that remarriage was common, and families might be composed of multiple primary couples or even the reassembled components of those pairs once severed by death or flight. Spouses often split over the decision to relocate. Other couples split and separately relocated as a solution to restrictive 19th-century divorce laws. As a consequence, casual, if quiet bigamists were commonplace in frontier communities.

Regardless, many settlers left families in the East and attempted to create new ones in the West. Constituting new families among the scattered and diverse population of the West often involved cross-class and cross-race marriages that would have been unthinkable in Eastern urban communities. Forced resettlement frequently shattered slave families and forced enslaved people to repeatedly reconstitute their families.

Rural people applied a make-do attitude not just to work and family, but to sexual intimacy as well. Camps, bunkhouses, lodges, taverns, and saloons were spaces rife with intimate and sexual relations that directly contravened dominant middle-class notions of sexual propriety: homosexuality, sexual barter and commerce, public and semi-public sex, and cross-dressing and gender fluidity.

Country folk were eager to pay for sex as well, and a distinctively rural infrastructure of sexual commerce met their desires. Brothels and prostitutes in rented rooms were common enough in frontier towns, but historians Estelle Freedman and John D’Emilio also describe euphemistically named “hog farms” — farms that also operated as brothels. Matching the mobility of rural populations, other enterprising sex merchants put their brothels on wheels. Many states worked to criminalize “cat wagons,” as the mobile brothels were known, forbidding prostitution in “any such prairie schooner, covered wagon or vehicle,” as a 1899 South Dakota law put it.

Rural spaces were also hotbeds for sexual diversity. Close quarters and cold nights meant that many men slept together, and in timber camps and other gatherings of migrant laborers, proximity led to sex. Historian Peter Boag surveyed reports about camps in the Pacific Northwest and found that reliable reports estimated incidences of same-sex intimacy among men (and often adolescent boys) ranged from common to pervasive.

Similarly, itinerant laborers were a constant source of sexual anxiety among the better sorts in agricultural communities: A hired man might corrupt the farmer’s daughter . . . or his son. Social reformers also fretted that constant exposure to animal sex on farms produced unnatural desires. The sociologist E. A. Ross memorably quoted a Wisconsinite who reported that farm boys “get together in the barn and while away the long winter evenings talking obscenity, telling filthy stories, recounting sex exploits, encouraging one another in vileness, perhaps indulging in unnatural practices.”

What precisely these “unnatural practices” entailed was left unsaid, but decades later Alfred Kinsey would report that homosexuality was most common “in particular rural communities in some of the more remote sections of the country . . . among ranchmen, cattle men, prospectors, lumbermen, and farming groups in general.” Such men often formed complex sexual communities with visible public components such as all-male “stag,” “bull,” and “cowboy” dances as well as stable intergenerational relationships between older “wolves” and “jockers” and younger “punks” and “lambs.”

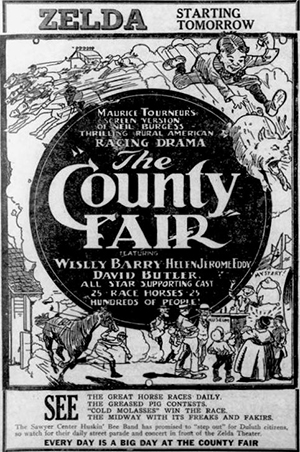

Rural social events often scandalized middle-class observers. Rural people took the rare sociality afforded by fairs, festivals, and weddings to let loose. Such events rippled with gambling, drink, dance, and sex. Far from quaint, quiet, or orderly affairs, rural public events could be bawdy and rambunctious. Despairing of the corrupting effects of a “whisky, colored to resemble red lemonade,” an 1876 account from Dearborn, Ind., declared, “Thus did an agricultural fair, a promised event of sobriety and chastity, run to the resemblance of a drunken orgie.” Many fair associations responded to these problems by banning alcohol and gambling, but enough rowdiness persisted that in the 1920s the sociologist Alvin Good still bitterly complained, “Even the public dance in the rural community is usually sponsored by the immoral elements, and alcohol is usually consumed in abundance.”

At the turn of the century, such laments were entirely common. Commentators rarely looked out on rural families and communities as models of propriety, chastity, and virtue. Instead, they saw distressing disorder. The Social Gospel activist Josiah Strong captured the sentiment best in 1893. Observing the chaotic churn of populations in and out of rural communities, Strong announced he could “see no reason why isolation, irreligion, ignorance, vice and degradation should not increase in the country until we have a rural peasantry, illiterate and immoral, possessing the rights of citizenship, but utterly incapable of performing or comprehending its duties.” He called this endemic “degeneration and demoralization” in rural areas, and he prescribed a hearty reordering of rural family life as a tonic.

This reordering was broad-based, national, and highly invasive in its scope. It enrolled ministers, educators, reformers, and government officials. It produced numerous legal reforms such as the “cat wagon” laws as well as other prostitution, vice, and temperance reforms. Alongside these measures, reformers targeted rural public health and hygiene and decrepit country schoolhouses. But reformers also supported eugenic sterilization and marriage registry laws, justifying the measures by appealing to some rural families.

In addition to taking legal measures, rural civil society cracked down on degeneracy. Local vice and social hygiene committees bolstered clean and sober social opportunities, expelled immoral elements from dances and fairs, and provided moral supervision to impressionable farm youth. Agrarian reformer and journalist Henry Wallace, for example, implored his readers in 1911 to clean up their fairs such that they no longer “offer[ed] temptations to vice and immorality.” Similarly, the country church movement aimed to boost the presence and potency of an effective ministry in rural communities. As historian Colin Johnson notes, other reformers endeavored to reach even the most remote reprobates through mail-order social hygiene and anti-vice education schemes.

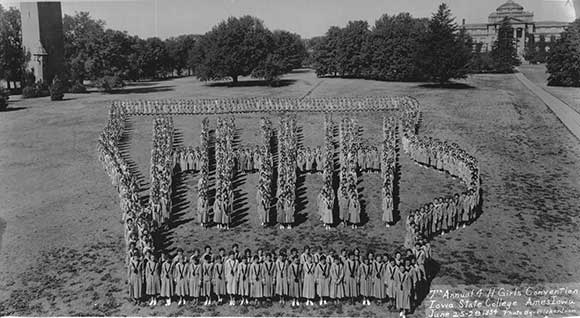

The Country Life Movement, helmed by President Theodore Roosevelt, invested federal resources in the effort. Its efforts bore the fruit of a federal educational agency called the Cooperative Extension Service, or CES, in 1914. The CES provided agricultural advice to farmers, but it also circulated moral proscriptions and organized youth clubs, later called 4-H clubs, that emphasized gender-appropriate labor, clean living, and supervised social events. By the 1930s, officials at the Department of Agriculture, the CES’s parent agency, bragged that 4-H clubs were teaching millions of rural youth how to build stable families in the countryside, families that fit the gendered order and social stability we only now impute to family farms. In fact, it was only at this moment in American history that the term “family farm” itself emerged as a celebratory ideal, and it did so primarily in the context of government officials and their allies’ rallying the public to reform rural family life.

In this sense, our contemporary political mythology built on the family farm is actually founded on a backlash to a much more complicated history. Our political mythology insistently suppresses that rich, if imperfect human history. Rural America — its landscapes and communities both — did not spring from a process of peaceful, orderly, or permanent settlement. Those processes were tumultuous, violent, and chaotic. What was settled needed to be resettled and resettled again — wave after wave of individuals and families crashing against a wall of grueling deprivation.

Farmers have always been at the cutting edge of North American territorial and ecological colonization. They have also frequently been among its victims. The story of rural America, then, is not that of the permanence we hope to capture in the family farm. It is a story of profound dislocation and loss, and it is the story of the very human struggle to form family, intimacy, and belonging — in all of their marvelous diversity — in the wake of that monumental violence.